Tamar Haspel is a freelance journalist who has been writing monthly food columns for the Washington Post since October 2013. Her columns frequently promote and defend pesticide industry products, while she also receives payments to speak at industry-aligned events, and sometimes from industry groups. This practice of journalists receiving payments from industry groups, known as “buckraking,” raises questions about objectivity.

A review of Haspel’s Washington Post columns turns up further concerns. In multiple instances, Haspel failed to disclose or fully describe the industry connections of her sources, relied on industry-slanted studies, cherry-picked facts to back up industry positions, or cited industry propaganda uncritically. See our source review for documentation. Haspel has not yet responded to inquiries for this article.

Agrichemical funding conflicts of interest

“I speak and moderate panels and debates often, and it’s work I’m paid for,” Haspel wrote in a 2015 online chat hosted by theWashington Post, in response to a question about whether she receives money from industry sources. Haspel said she discloses her speaking engagements on her personal website, but she does not disclose which companies or groups fund her, or what amounts they give.

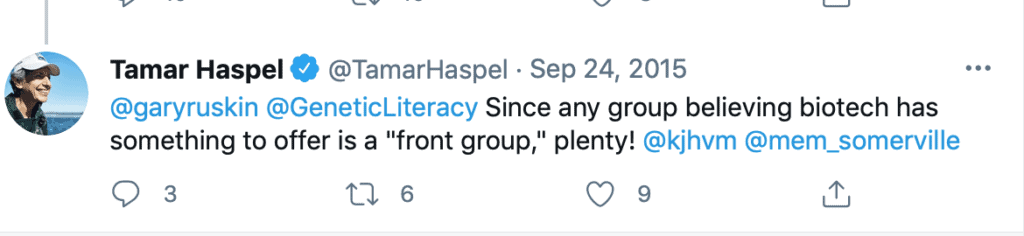

When asked how much money she has taken from the agrichemical industry and its front groups, Haspel tweeted, “Since any group believing biotech has something to offer is a ‘front group, ’ plenty!”

According to the Washington Post Standards and Ethics, reporters cannot accept gifts, free trips, preferential treatment or free admissions from news sources, and “should make every effort to remain in the audience, to stay off the stage, to report the news, not to make the news.” These rules do not apply to freelancers however, and the paper leaves it up to editors to decide.

Haspel’s editor Joe Yonan has said he is comfortable with Haspel’s approach to paid speaking engagements and finds it a “reasonable balance.”

For more information:

- Buckraking on the Food Beat: When is it a Conflict of Interest? by Stacy Malkan, Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting (2015)

- A short report on three journalists mentioned in our FOIA requests, by Gary Ruskin, U.S. Right to Know (2015).

- For perspectives from journalists and editors on buckraking, see Ken Silverstein’s reporting in Harper’s (2008).

Pro GMO beat

Haspel began writing about genetically engineered foods in March 2013 in the Huffington Post (“Go Frankenfish! Why We Need GM Salmon”). Her final series of articles for Huffington Post focused favorably on agrichemical industry products. She debunked the risks of glyphosate and GMO animal feed, argued against GMO labeling campaigns, and promoted the pesticide industry-funded website GMO Answers. That site was part of a multi-million dollar public relations initiative to combat consumer concerns about genetically engineered foods in the wake of campaigns to label GMOs.

HuffPo July 2013: An example of how Haspel has promoted industry sources uncritically. More examples below.

Haspel launched her monthly “Unearthed” food column in the Washington Post soon afterward, in October 2013, with an article about “what is and isn’t true” about GMOs. She promisedto “dig deep to try and figure out what’s true and what isn’t in the debate about our food supply.” She advised readers to figure out “whom you can trust” in the GMO debate and identified several groups that did not pass her impartiality test; the Union of Concerned Scientists was among them.

Haspel’s next column, “GMO common ground: Where supporters and opponents agree,” provided a broad range of perspectives from public interest as well as industry sources. However, in subsequent columns, Haspel seldom quoted public interest groups and devoted far less space to public health sources than to industry-connected sources. She often quotes experts in “risk perception” who tend to downplay public health and safety concerns. In several instances, Haspel failed to disclose or fully describe industry ties to sources when reporting on GMOs, pesticides or organic foods.

Industry-sourced ‘food movement’ column

An example that illustrates problems of bias is Haspel’s January 2016 column, “The surprising truth about the food movement.” She argues that people who care about genetic engineering or other aspects of food production – the “food movement” – are a marginal part of the population. She included no interviews with consumer, health, environmental or justice groups that consider themselves part of the food movement.

Haspel sourced the column with two industry-funded spin groups, the International Food Information Council and Ketchum, the public relations firm that runs the pesticide industry-funded website GMO Answers. While she described Ketchum as a PR firm that “works extensively with the food industry,” Haspel did not disclose the background: that Ketchum was hired by a trade association to change consumer views of GMO foods. She also did she mention Ketchum’s scandalous history of flacking for Russia and conducting espionage against environmental groups.

A third source for her column was a two-year oldphone survey conducted by William Hallman, a public perception analyst from Rutgers who reported that most people don’t care about GMO labeling. A year earlier, Hallman and Haspel had appeared together on agovernment-sponsored panel to discuss GMOs with Eric Sachs of Monsanto.

Collaborations with industry spin groups

Tamar Haspel’s affinity for, and collaborations with, key players in the agrichemical industry’s public relations efforts raise further concerns about her objectivity.

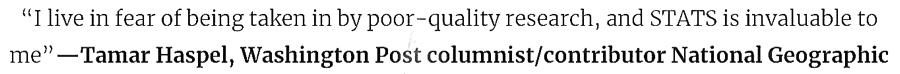

The above promotional quote appears on the homepage of STATS/Sense About Science, describing STATS as “invaluable” to her reporting. Other journalists have described STATS as a product-defense “disinformation campaign” that uses tobacco tactics to manufacture doubt about chemical risk. STATs played a key rolein the “hardball politics of chemical regulation” and the industry’s efforts to discredit health concerns about bisphenol-A, according to reporting in the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.

A 2016 story in The Intercept described the tobacco ties of STATS and Sense About Science, which merged in 2014, and the role these groups play in pushing industry views about science.A 2015 public relations strategy document named Sense About Science among the “industry partners” Monsanto planned to engage in its campaign to “orchestrate outcry” against the World Health Organization’s cancer research agency to discredit a report about the carcinogenicity of glyphosate.

Agrichemical industry spin events

In June 2014, Haspel was a “faculty” member at a pesticide industry-funded messaging training event called the Biotech Literacy Project Boot Camp. The event was organized by the Genetic Literacy Project and Academics Review, two industry front groups Monsanto also identified as “industry partners” in its 2015 PR plan.

Genetic Literacy Project is a former program of STATS, and Academics Review was set up with the help of Monsanto to discredit industry critics while keeping corporate fingerprints hidden, according to emails obtained through public records requests.

The boot camp Haspel attended was aimed at “reframing the food safety and GMO debate,” according to the agenda.Paul Thacker reported about the event in The Progressive, “Industry has also secretly funded a series of conferences to train scientists and journalists to frame the debate over GMOs and the toxicity of glyphosate … In emails, organizers referred to these conferences as biotech literacy bootcamps, and journalists are described as ‘partners.'”

Academics familiar with corporate spin tactics reviewed the boot camp documents at Thacker’s request. “These are distressing materials,” said Naomi Oreskes, professor of the history of science at Harvard University.”It is clearly intended to persuade people that GMO crops are beneficial, needed, and not sufficiently risky to justify labeling.” Marion Nestle, professor of nutrition, food studies, and public health at New York University, said, “If journalists attend conferences that they are paid to attend, they need to be deeply suspicious from the get-go.”

Cami Ryan, a boot camp staffer who later went on to work for Monsanto, noted in the conference evaluation that participants wanted, “More Haspel-ish, Ropeik-ish sessions.” David Ropeik is arisk perception consultant whose clients include Bayer and other chemical companies, and whom Haspel used as a source in a column she wrote about glyphosate.

Industry funded biotech messaging conferences

In May 2015, Haspel presented at a “biotechnology literacy and communications day ” at the University of Florida. The event was organized by Kevin Folta, a professor tied in with agrichemical industry public relations and lobbying efforts.Folta had even included Haspel in a proposal he sent to Monsanto seeking funding for events he described as “a solution to the biotech communications problem.” The problem, Folta said, was due to activists’ “control of public perception” and their “strong push for clunky and unnecessary food labeling efforts.” On Page 4, Folta described an event that would feature UF professors along with “industry representatives, journalist experts in science communication (e.g. Tamar Haskel [sic], Amy Harmon), and experts in public risk perception and psychology (e.g. Dan Kahan).”

Monsanto funded the proposal, calling it “a great 3rd-party approach to developing the kind of advocacy we’re looking to develop.” (The money was later donated to a food pantry after the funding source became public.)

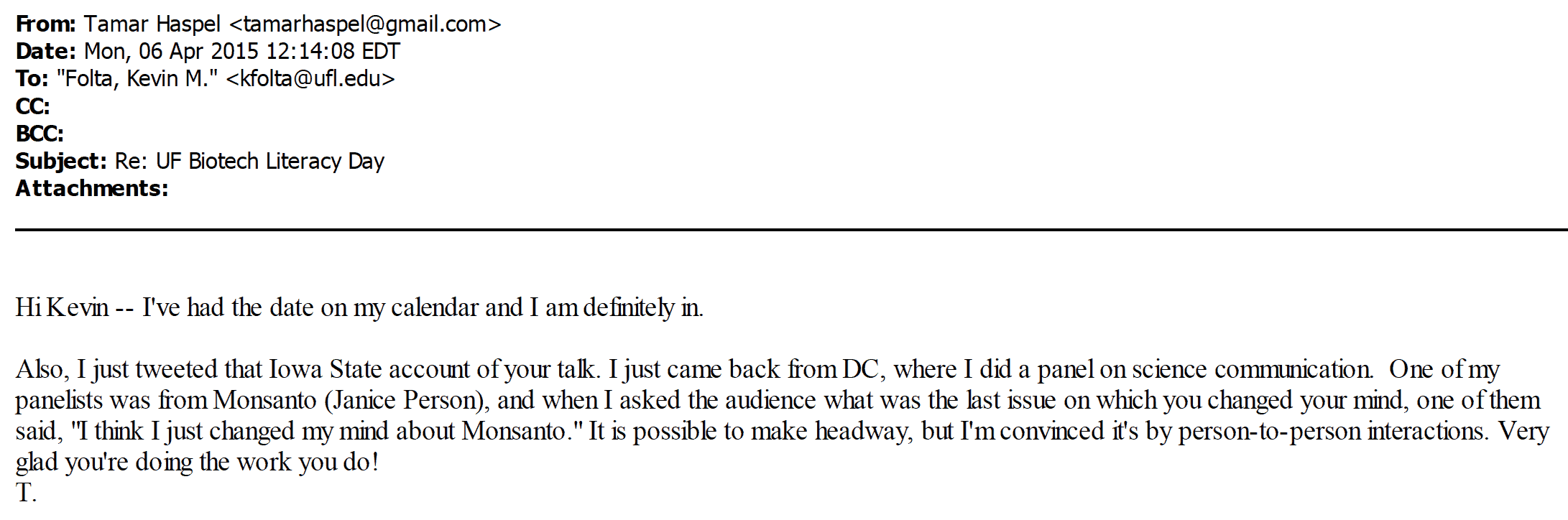

In April 2015, Folta wrote to Haspel with details about the messaging training event, “We’ll cover the costs and an honorarium, whatever that takes. The audience will be scientists, physicians and other professionals that need to learn how to talk to the public.”

Haspel responded, “I am definitely in,” and she relayed an anecdote from another recent “science communication” panel that had changed somebody’s view about Monsanto. “It is possible to make headway, but I’m convinced it’s by person-to-person interactions,” Haspel wrote to Folta.

The archived agenda for the Florida communication day listed the speakers as Haspel, Folta, three other UF professors, Monsanto employee Vance Crowe and representatives from Biofortified and Center for Food Integrity (two more groups Monsanto referred to as industry partners in its PR strategyto defend glyphosate). In another email to Folta, Haspel enthused about meeting Crowe, “Very much looking forward to this. (I’ve wanted to meet Vance Crowe – very glad he’ll be there.)”

Ethics and disclosure questions

In September 2015, The New York Times featured Folta in a front-page story by Eric Lipton about how industry groups relied on academics to fight the GMO labeling war. Lipton reported on Folta’s fundraising appeal to Monsanto, and that Folta had been publicly claiming he had no associations with Monsanto.

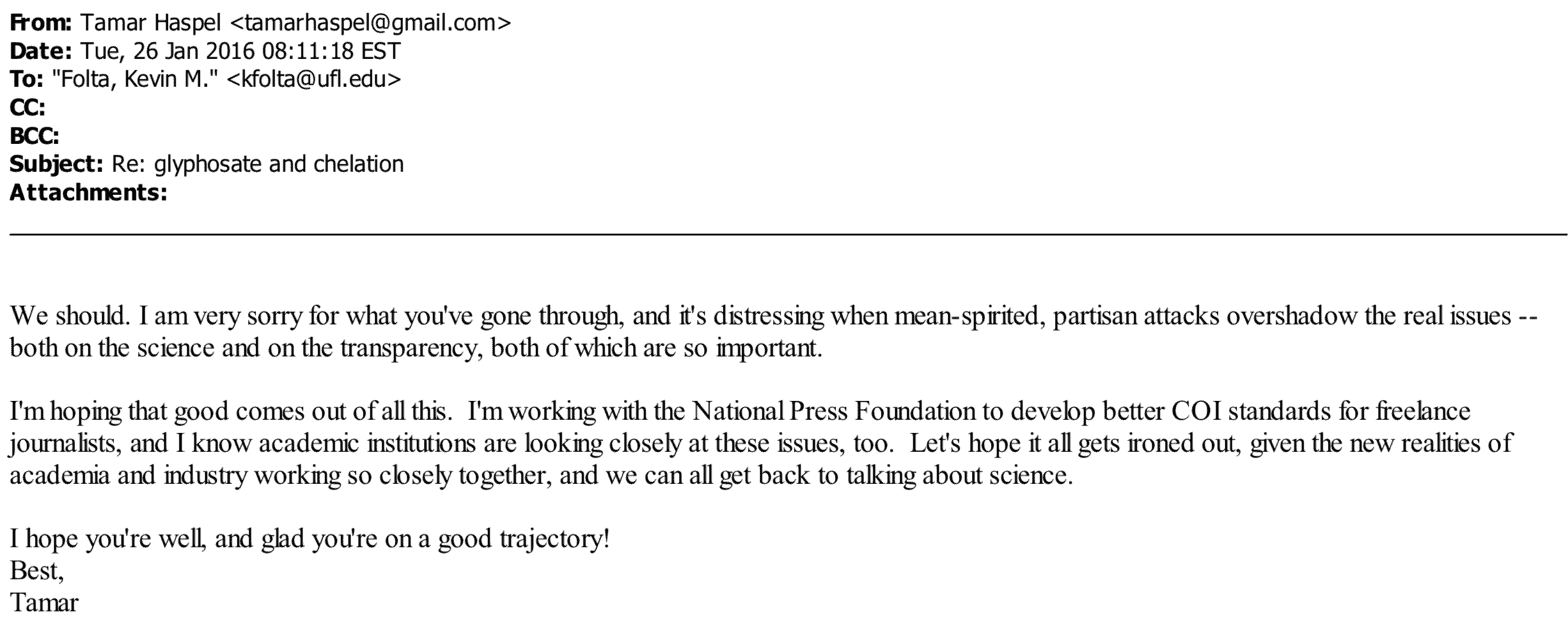

Haspel wrote to Folta a few months later, “I am very sorry for what you’ve gone through, and it’s distressing when mean-spirited, partisan attacks overshadow the real issues — both on the science and on the transparency, both of which are so important.” Haspel mentioned she was working with the National Press Foundationto develop better conflict of interest standards for freelance journalists.

Haspel was a 2015 fellow for the National Press Foundation (a group partly funded by corporations, including Bayer and DuPont). In an article she wrote for NPF about ethics for freelancers, Haspel discussed the importance of disclosure and described her criteria for speaking at events only if non-industry funders and diverse views are involved — criteria not met by either of the biotech literacy events. The disclosure page on her website does not accurately disclose the conveners and funders of the 2014 biotech literacy boot camp. Haspel has not responded to questions about the biotech literacy events.

Source review: misleading reporting about pesticides

A source review of three of Tamar Haspel’s Washington Post columns on the topic of pesticides found multiple concerning examples of undisclosed industry-connected sources, data omissions and out-of-context reporting that served to bolster pesticide industry messaging that pesticides are not a concern and organic is not much of a benefit. The source review covers these three columns:

- “Is organic better for your health? A look at milk, meat, eggs, produce and fish” ( April 7, 2014)

- “It’s the chemical Monsanto depends on. How dangerous is it?”( October 2015)

- “The truth about organic produce and pesticides”( May 21, 2018)

Relied on industry-connected sources; failed to disclose industry ties

In all three of the columns cited in this source review, Haspel failed to disclose pesticide industry connections of key sources who downplayed the risk of pesticides.None of the following industry connections were mentioned in her columns as of August 2018 when this review was published.

In her 2018 report on the “truth about organic produce and pesticides,” Haspel gave readers “an idea of the magnitude of risk” from cumulative pesticide exposures by citing astudy that equated therisk of consuming pesticides from food to drinking wine. Haspel did not disclose that four of five authors of the study were employed by Bayer Crop Sciences, one of the world’s largest pesticide manufacturers.

She also did not inform her readers that the original study contained a glaring error that was later corrected (even though her column linked to both the original and corrected study). The study first equated pesticide exposures from food as equal to drinking one glass of wine every seven years. The authors later corrected that to one glass of wine every three months.That was only one of several errors in the paper, according to a letter to the journal from scientists who described the study as “overly simplistic and seriously misleading.”

To dismiss concerns about the synergistic effects of exposure to multiple pesticides, Haspel cited another study from the only non-Bayer affiliated author of the flawed wine-comparison study. And she cited “a 2008 report ” that “made the same assessment.” Authors of that 2008 report included Alan Boobis and Angelo Moretto, two academics who were caught in a conflict of interest scandal in 2016 because they chaired a UN panel that exonerated glyphosate of cancer risk at the same time as they held leadership positions in the International Life Sciences Institute, a nonprofit group that received substantial donations from the pesticide industry.

In her 2015 column about the risk of glyphosate, the “chemical Monsanto depends on,” Haspel quoted two sources with pesticide industry connections she didn’t disclose. The sources were Keith Solomon, atoxicologist who wrote papers about glyphosate that were funded by Monsanto (and whom Monsanto was promoting as a source); andDavid Ropeik, a risk perception consultant who has a PR firm whose clients include Dow, DuPont and Bayer.

In her 2014 column about whether pesticide residues in food pose a health risk, Haspelintroduced doubt about the health risks of organophosphates, a class of pesticides linked to neurological damage in children. She cited a review that found “the epidemiological studies did not strongly implicate any particular pesticide as being causally related to adverse neurological developmental outcomes in infants and children.” The lead author was Carol Burns, a scientist at Dow Chemical Company, one of the country’s largest manufacturers of organophosphates; the connection was not disclosed.

That column also usedindustry go-to toxicologist Carl Winter as a source vouching for the safety of pesticide residues in food, based on EPA risk assessments.Monsanto was promoting Winter’s work at that time in talking points, and Winter also served on the science advisory board of the Monsanto-funded group American Council on Science and Health, which bragged in a blog post a few months earlier about anti-organic press coverage that quoted their guy, “ACSH advisor Dr. Carl Winter.”

Misled with out-of-context reporting

In her 2014 column about organic food, Haspel used a 2012 paper by the American Academy of Pediatrics out of context to reinforce her argument that eating organic might not offer health benefits, and she did not inform readers of the full scope of the study or its conclusions. The AAPpaper reported a wide range of scientific evidence suggesting harm to children from both acute and chronic exposures to various pesticides. It concluded, “Children’s exposures to pesticides should be limited as much as possible.” The report cited evidence of a “drastic immediate decrease in urinary excretion of pesticide metabolites” in children eating an organic diet. AAP also issued policy recommendations to reduce children’s exposure to pesticides.

Haspel left out all that context and reported only that the AAP report, “noted the correlation between organophosphate exposure and neurological issues that had been found in some studies but concluded that it was still ‘unclear’ that reducing exposure by eating organic would be ‘clinically relevant.'”

In her 2018 column about organic produce, Haspel misleadingly reported that the pesticidechlorpyrifos “has been the subject a battle between environmental groups, which want it banned, and the EPA, which doesn’t” — but she did not inform readers of a key point: that the EPA had recommendedbanning chlorpyrifos due to mounting evidence that prenatal exposure could have lasting effects on children’s brains. The agency reversed course only after the Trump EPA interfered.

Haspel sourced hermisleading “environmental groups vs EPA” comparison with a link to a New York Times documents page that provided no context about the EPA decision, rather than linking to the NYT story that reported on corporate influence behind the EPA decision to allow chlorpyrifos.

Relied on sources who agree with eachother

In her 2018 column, Haspel set up her argument that pesticide exposures in food are not much of a concern with a dubious reporting tactic she has used on other occasions: citing agreement among many unnamed sources.

In this case, Haspel reported that pesticidelevels in food “are very low” and “you shouldn’t be concerned about them,” according to U.S. government agencies “(along with many toxicologists I’ve spoken with over the years).”Although she reported that “not everyone has faith” in those government assessments, Haspel cited no disagreeing sources and ignored entirely the American Academy of Pediatrics report that recommended reducing children’s exposures to pesticides, which she cited out of context in her 2014 column.In her 2015 column about glyphosate, she again quoted like-minded sources, reporting that “every” scientist she spoke with said that, until recent questions arose, “glyphosate had been noted for its safety.”

Missed relevant data

Haspel missed plenty of relevant data in her “get to the bottom of it” reporting on the risks of pesticides and the benefits of organic. Recent statements by prominent health groups and science she missed include:

- January 2018 study by Harvard researchers published in in JAMA Internal Medicinereporting that women who regularly consumed pesticide-treated fruits and vegetables had lower success rates getting pregnant with IVF, while women who ate organic food had better outcomes;

- January 2018 commentary in JAMA by pediatrician Phillip Landrigan urging physicians to encourage their patients to eat organic;

- February 2017 report prepared for the European Parliament outlining the health benefits of eating organic food and practicing organic agriculture;

- 2016 European Parliament Science and Technology Option Assessment recommended reducing dietary intake of pesticides, especially for women and children;

- 2012 President’s Cancer Panel report recommends reducing children’s exposure to cancer-causing and cancer-promoting environmental exposures;

- 2012 paper and policy recommendation from the American Academy of Pediatrics recommending reducing children’s exposure to pesticides as much as possible;

- 2009 statement by the American Public Health Association, “Opposition to the use of hormone growth promoters in beef and dairy cattle production”;

- 2002 review bythe European Union’s Scientific Committee on Veterinary Measures Review reporting that growth-promoting hormones in beef production pose a health risk to consumers.

More perspectives on Haspel’s reporting

- “The food movement is small? Not from where we sit, it isn’t,” byChellie Pingree and Anna Lappé, Washington Post (2.4.2016)

- “Washington Post food columnist goes to bat for Monsanto — again,” by Stacy Malkan, Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting (2.4.2016)

- Buckraking on the Food Beat: When is it a Conflict of Interest?” by Stacy Malkan, Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting (10.28.2015)

- “Response to ‘Is Organic Better for Your Health?'” The Organic Center (4.8.2014)

- “The Assault on Organic: Ignoring science to make the case for chemical farming,” by Kari Hamerschlag and Stacy Malkan, Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting (7.2014)