Long History of Concerns

Key Scientific Studies on Aspartame

Industry PR Efforts

Key facts about aspartame

Dozens of studies have linked the popular artificial sweetener aspartame to serious health problems, including cancer, cardiovascular disease, Alzheimer’s disease, seizures, stroke and dementia, as well as negative effects such as intestinal dysbiosis, mood disorders, headaches and migraines. Aspartame is found in about 6,000 products, including Diet Coke and many other products marketed as “diet.”

Evidence also links aspartame to weight gain, increased appetite and obesity-related diseases. See our fact sheet: Aspartame is tied to weight gain. This evidence raises questions about the legality of marketing aspartame-containing products as “diet” drinks or weight-loss products.

In April 2015, US Right to Know petitioned the Federal Trade Commission and the Food and Drug Administration to investigate the marketing and advertising practices of “diet” products containing aspartame. The agencies declined to take action (see FTC response and FDA response).

In July 2023, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) classified aspartame as “possibly carcinogenic to humans.” The World Health Organization/FAO Joint Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA) reaffirmed the enormous acceptable daily intake of 40 mg/kg body weight. See IARC/JECFA statement. Research by U.S. Right to Know found at least six of 13 JECFA panel members have ties to ILSI, a longtime Coca-Cola front group – including both the chair and vice chair of the JECFA panel: Did a Coca-Cola front group sway a WHO review of aspartame?

In May 2023, the WHO advised people not to consume non-sugar sweeteners for weight loss, including aspartame. The recommendation is based on a systematic review of the most current scientific evidence, which suggests that consumption of non-sugar sweeteners is associated with increased risk of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases and all-cause mortality, as well as increased body weight.

The FDA has said aspartame is “safe for the general population under certain conditions.” The agency first approved aspartame for some uses in 1981. Many scientists, then and now, have said the approval was based on suspect data and should be reconsidered.

Many popular beverages – including Diet Pepsi and Diet Coke – contain aspartame.

What is aspartame?

Aspartame is an artificial sweetener — also marketed as NutraSweet, Equal, Sugar Twin and AminoSweet — used in more than 6,000 products, including Diet Coke and Diet Pepsi, Kool Aid, Crystal Light, Tango and other artificially sweetened drinks; sugar-free Jell-O products; Trident, Dentyne and most other brands of sugar-free gum; sugar-free hard candies; low- or no-sugar sweet condiments such as ketchups and dressings; children’s medicines and vitamins

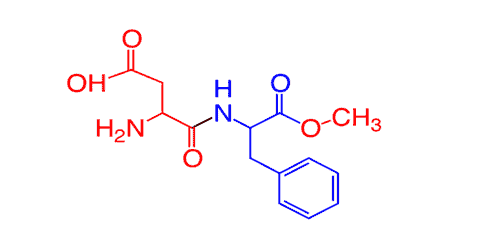

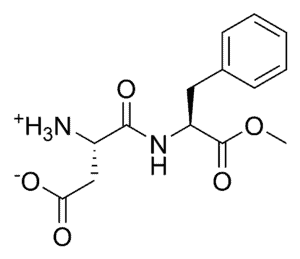

Aspartame (known as E 951 in the European Union) is a synthetic chemical composed of the amino acids phenylalanine and aspartic acid, with a methyl ester. When consumed, the methyl ester breaks down into methanol, which may be converted into formaldehyde. Its chemical structure can be seen below.

Decades of studies raise health concerns about aspartame

Since aspartame was first approved in 1974, FDA scientists and independent scientists have both raised concerns about negative effects of aspartame and shortcomings in the science submitted to the FDA by the manufacturer, G.D. Searle. (Monsanto bought Searle in 1984).

In 1987, UPI published a series of investigative articles by Gregory Gordon reporting on these concerns, including early studies linking aspartame to health problems, the poor quality of industry-funded research that led to its approval, and the revolving-door relationships between FDA officials and the food industry. Gordon’s series is an invaluable resource for anyone seeking to understand the history of aspartame/NutraSweet:

- Did Searle Ignore Early Warning Signs? (10/12/87)

- Seizure, Blindness Victims Point to NutraSweet (10/12/87)

- What the Critics Say about NutraSweet (10/12/87)

- NutraSweet Approval Marred by Controversy (and part 2) (10/13/87)

- Maverick Scientist at Center of NutraSweet Controversy (10/13/87)

- Sweet Corporate Victories (10/14/87)

- These articles, follow ups and response from NutraSweet Company are posted here (PDF).

Aspartame studies point to serious health risks

While many studies, some of them industry sponsored, have reported no problems with aspartame, dozens of independent studies conducted over decades have linked aspartame to a long list of health problems. Aspartame risks include:

Cancer

An April 2025 study in Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety “provided substantial evidence that aspartame is a risk factor for the development of liver cancer …. our study reveals that aspartame induces liver cancer…”

In May 2024, the World Health Organization’s cancer research agency, the IARC, published its full monograph on aspartame. As announced in January, IARC found aspartame is possibly carcinogenic. The monograph notes that a minority of the working group supported classifying aspartame as “probably carcinogenic to humans,” based on “a combination of limited evidence for cancer in humans and sufficient evidence for cancer in experimental animals, supported by the limited mechanistic evidence…”

A large 2022 cohort study in PLOS Medicine involving 102,865 French adults found that artificial sweeteners — especially aspartame and acesulfame-K — were associated with increased cancer risk. Higher risks were observed for breast cancer and obesity-related cancers. “These findings provide important and novel insights for the ongoing re-evaluation of food additive sweeteners by the European Food Safety Authority and other health agencies globally,” the researchers wrote.

- Study suggests association between consuming artificial sweeteners and increased cancer risk, Science Daily (3.24.2022)

Three lifespan studies conducted by the Cesare Maltoni Cancer Research Center of the Ramazzini Institute, provide consistent evidence of carcinogenicity in rodents exposed to the substance.

- Aspartame “is a multipotential carcinogenic agent, even at a daily dose of … much less than the current acceptable daily intake,” according to a 2006 lifespan rat study in Environmental Health Perspectives.

- A follow-up study in 2007 found significant dose-related increases in malignant tumors in some of the rats. “The results … confirm and reinforce the first experimental demonstration of [aspartame’s] multipotential carcinogenicity at a dose level close to the acceptable daily intake for humans … when life-span exposure begins during fetal life, its carcinogenic effects are increased,” the researchers wrote in Environmental Health Perspectives.

- The results of a 2010 lifespan study “confirm that [aspartame] is a carcinogenic agent in multiple sites in rodents, and that this effect is induced in two species, rats (males and females) and mice (males),” the researchers reported in American Journal of Industrial Medicine.

In a 2021 review of the Ramazzini Institute data, researchers at Boston College validated the conclusions of the studies. See, Aspartame and cancer — new evidence of causation, Environmental Health. The findings, “confirm that aspartame is a chemical carcinogen in rodents. They confirm the very worrisome finding that prenatal exposure to aspartame increases cancer risk in rodent offspring.”

A 2023 study by the Ramazzini Institute in the Annals of Global Health reports on all the detailed haemolymphoreticular neoplasias (HLRN) diagnoses of the Ramazzini Institute rats and mice studies on aspartame and the related statistics. “Our analyses … confirm and reinforce our previous findings of statistically significant increases of HLRNs in rodents exposed to (aspartame) … The presence of different highly significant results and dose-related increased trends in multiple studies highlight the biological relevance of our findings.”

Harvard researchers in 2012 reported in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition a positive association between aspartame intake and increased risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma and multiple myeloma in men, and for leukemia in men and women. The findings “preserve the possibility of a detrimental effect … on select cancers” but “do not permit the ruling out of chance as an explanation,” the researchers wrote

In a 2014 commentary in American Journal of Industrial Medicine, the Maltoni Center researchers wrote that the studies submitted by G. D. Searle for market approval “do not provide adequate scientific support for [aspartame’s] safety. In contrast, recent results of life-span carcinogenicity bioassays on rats and mice published in peer-reviewed journals, and a prospective epidemiological study, provide consistent evidence of [aspartame’s] carcinogenic potential. On the basis of the evidence of the potential carcinogenic effects … a re-evaluation of the current position of international regulatory agencies must be considered an urgent matter of public health.”

Research published in Scientific Reports in May 2024 employed network toxicology and molecular docking techniques to systematically examine the potential carcinogenic effects and mechanisms of aspartame.”The findings suggest that aspartame has the potential to impact various cancer-related proteins, potentially raising the likelihood of cellular carcinogenesis by interfering with biomolecular function. Furthermore, the study found that the action patterns and pathways of aspartame-related targets are like the mechanisms of known carcinogenic pathways, further supporting the scientific hypothesis of its potential carcinogenicity.”

Transgenerational impacts: Anxiety and learning deficits

A 2022 study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences reports that exposure of mice to aspartame at doses equivalent to below 15% of the FDA recommended daily intake for humans produces anxiety-like behavior. The anxiety appears in up to two generations descending from the aspartame-exposed males. “These data do not merely add anxiety to the long list of aspartame’s adverse effects, but also raise the previously unrecognized possibility that aspartame’s adverse effects are not limited to the individuals who consume it but persist for generations to come,” the researchers wrote. “Therefore, aspartame deserves a place on the list of environmental agents such as hormones, insecticides, and drugs of abuse whose adverse effects are not limited to the exposed individuals but manifest in multiple generations of descendants.”

- FSU research links common sweetener with anxiety, by Robert Thomas, Florida State University News (12.8.22)

A 2023 study in Scientific Reports suggests that daily consumption of aspartame at doses equivalent to only 7–15% of the FDA recommended maximum daily intake value (2–4 small, 8 oz diet soda drinks per day) produces “significant spatial learning and memory deficits in mice. Moreover, the cognitive deficits are transmitted to male and female descendants along the paternal lineage suggesting that aspartame’s adverse cognitive effects are heritable, and that they are more pervasive than current estimates, which consider effects in the directly exposed individuals only.”

The researchers said the study demonstrates “the need for considering heritable effects via the paternal lineage as part of the regulatory evaluations of artificial sweeteners.”

Brain tumors

In 1996, researchers reported in the Journal of Neuropathology & Experimental Neurology on epidemiological evidence connecting the introduction of aspartame to an increase in an aggressive type of malignant brain tumors. “Compared to other environmental factors putatively linked to brain tumors, the artificial sweetener aspartame is a promising candidate to explain the recent increase in incidence and degree of malignancy of brain tumors … We conclude that there is need for reassessing the carcinogenic potential of aspartame.”

- Neuroscientist Dr. John Olney, lead author of the study, told 60 minutes in 1996: “there has been a striking increase in the incidence of malignant brain tumors (in the three to five years following the approval of aspartame) … there is enough basis to suspect aspartame that it needs to be reassessed. FDA needs to reassess it, and this time around, FDA should do it right.”

Studies on aspartame in the 1970s found evidence of brain tumors in laboratory animals, but those studies were not followed up.

Cardiovascular disease

In a 2025 study published in Cell Metabolism, a team of cardiovascular health experts and clinicians found that aspartame triggers increased insulin levels in animals, which contributes to atherosclerosis—buildup of fatty plaque in the arteries. This can lead to higher levels of inflammation and an increased risk of heart attacks and stroke over time.

- Artificial sweetener triggers insulin spike, leading to blood vessel inflammation in mice, Medical XPress (2.19.25)

A 2017 meta-analysis of research on artificial sweeteners, published in the Canadian Medical Association Journal, found no clear evidence of weight loss benefits for artificial sweeteners in randomized clinical trials, and reported that cohort studies associate artificial sweeteners with “increases in weight and waist circumference, and higher incidence of obesity, hypertension, metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular events.” See also:

- Artificial sweeteners don’t help with weight loss and may lead to gained pounds, by Catherine Caruso, STAT (7.17.2017)

- Why one cardiologist has drunk his last diet soda, by Harlan Krumholz, Wall Street Journal (9.14.2017)

- This cardiologist wants his family to cut back on diet soda. Should yours, too? by David Becker, M.D., Philly Inquirer (9.12.2017)

A 2016 paper in Physiology & Behavior reported, “there is a striking congruence between results from animal research and a number of large-scale, long-term observational studies in humans, in finding significantly increased weight gain, adiposity, incidence of obesity, cardiometabolic risk, and even total mortality among individuals with chronic, daily exposure to low-calorie sweeteners – and these results are troubling.”

Women who consumed more than two diet drinks per day “had a higher risk of [cardiovascular disease] events … [cardiovascular disease] mortality … and overall mortality,” according to a 2014 study from the Women’s Health Initiative published in the Journal of General Internal Medicine.

Stroke, dementia and Alzheimer’s disease

People drinking diet soda daily were almost three times as likely to develop stroke and dementia as those who consumed it weekly or less. This included a higher risk of ischemic stroke, where blood vessels in the brain become obstructed, and Alzheimer’s disease dementia, the most common form of dementia, reported a 2017 study in Stroke.

- Daily Consumption of Sodas, Fruit Juices and Artificially Sweetened Sodas Affect Brain, video of neurologist Matthew Pase, Boston University School of Medicine (4.20.2017)

- Study links diet soda to higher risk of stroke, dementia, by Fred Barbash, Washington Post (4.21.2017)

In the body, the methyl ester in aspartame metabolizes into methanol and then it may be converted to formaldehyde, which has been linked to Alzheimer’s disease. A two-part study published in 2014 in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease linked chronic methanol exposure to memory loss and Alzheimer’s Disease symptoms in mice and monkeys.

- “[M]ethanol-fed mice presented with partial AD-like symptoms … These findings add to a growing body of evidence that links formaldehyde to [Alzheimer’s disease] pathology.” ( Part 1)

- “[M]ethanol feeding caused long-lasting and persistent pathological changes that were related to [Alzheimer’s disease] … these findings support a growing body of evidence that links methanol and its metabolite formaldehyde to [Alzheimer’s disease] pathology.” ( Part 2)

Seizures

“Aspartame appears to exacerbate the amount of EEG spike wave in children with absence seizures. Further studies are needed to establish if this effect occurs at lower doses and in other seizure types,” according to a 1992 study in Neurology.

Aspartame “has seizure-promoting activity in animal models that are widely used to identify compounds affecting … seizure incidence,” according to a 1987 study in Environmental Health Perspectives.

Very high aspartame doses “might also affect the likelihood of seizures in symptomless but susceptible people,” according to a 1985 study in The Lancet. The study describes three previously healthy adults who had grand mal seizures during periods when they were consuming high doses of aspartame.

Neurotoxicity, brain damage and mood disorders

Aspartame side effects may also include behavioral and cognitive problems such as learning deficits, headache, seizure, migraines, irritable moods, anxiety, depression, and insomnia, according to the researchers of a 2017 study in Nutritional Neuroscience. “Aspartame consumption needs to be approached with caution due to the possible effects on neurobehavioral health.”

“Oral aspartame significantly altered behavior, anti-oxidant status and morphology of the hippocampus in mice; also, it may probably trigger hippocampal adult neurogenesis,” reported a 2016 study in Neurobiology of Learning and Memory.

“Previously, it has been reported that consumption of aspartame could cause neurological and behavioural disturbances in sensitive individuals. Headaches, insomnia and seizures are also some of the neurological effects that have been encountered,” according to a 2008 study in the European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. “[W]e propose that excessive aspartame ingestion might be involved in the pathogenesis of certain mental disorders … and also in compromised learning and emotional functioning.”

“(N)eurological symptoms, including learning and memory processes, may be related to the high or toxic concentrations of the sweetener [aspartame] metabolites,” states a 2006 study in Pharmacological Research.

Aspartame “could impair memory retention and damage hypothalamic neurons in adult mice,” according to a 2000 mice study published in Toxicology Letters.

“(I)ndividuals with mood disorders are particularly sensitive to this artificial sweetener and its use in this population should be discouraged,” according to a 1993 study in the Journal of Biological Psychiatry.

High doses of aspartame “can generate major neurochemical changes in rats,” reported a 1984 study in American Journal of Clinical Nutrition.

Experiments indicated brain damage in infant mice following oral intake of aspartate, and showing that “aspartate [is] toxic to the infant mouse at relatively low levels of oral intake,” reported a 1970 study in Nature.

Autism

An August 2023 study in MDPI reports that males with autism in the study “had more than tripled odds of having been exposed daily — gestationally and/or through breastfeeding — to either diet soda itself or comparable doses of aspartame from multiple sources. These exposure odds were the highest among cases with non-regressive autism. These associations do not prove causality. Taken in concert, however, with previous findings of increased prematurity and cardiometabolic health impacts among infants and children exposed daily to diet beverages and/or aspartame during pregnancy, they raise new concerns about the potential neurological impacts …” The researchers noted a recent study that provides evidence of transplacental passage of these substances in humans. “…these findings suggest that, in the spirit of the Precautionary Principle, women should exercise caution when considering the use of these products during pregnancy and breastfeeding…”

Headaches and migraines

“Aspartame, a popular dietetic sweetener, may provoke headache in some susceptible individuals. Herein, we describe three cases of young women with migraine who reported their headaches could be provoked by chewing sugarless gum containing aspartame,” according to a 1997 paper in Headache Journal.

A crossover trial comparing aspartame and a placebo published in 1994 in Neurology, “provides evidence that, among individuals with self-reported headaches after ingestion of aspartame, a subset of this group report more headaches when tested under controlled conditions. It appears that some people are particularly susceptible to headaches caused by aspartame and may want to limit their consumption.”

A survey of 171 patients at the Montefiore Medical Center Headache Unit found that patients with migraine “reported aspartame as a precipitant three times more often than those having other types of headache … We conclude aspartame may be an important dietary trigger of headache in some people,” 1989 study in Headache Journal.

A crossover trial comparing aspartame and a placebo on the frequency and intensity of migraines “indicated that the ingestion of aspartame by migraineurs caused a significant increase in headache frequency for some subjects,” reported a 1988 study in Headache Journal.

Weight gain, increased appetite and obesity related problems

Aspartame health risks include weight gain, increased appetite, diabetes, metabolic derangement and obesity-related diseases, according to several studies. See our fact sheet: Diet Soda Chemical Tied to Weight Gain.

This science linking aspartame to weight gain and obesity-related diseases raises questions about the legality of marketing aspartame-containing products as “diet” or weight loss aids. In 2015, USRTK petitioned the Federal Trade Commission and FDA to investigate the marketing and advertising practices of “diet” products that contain a chemical linked to weight gain. See related news coverage, response from FTC, and response from FDA.

Diabetes and metabolic derangement

A July 2023 analysis in Diabetes Care of 105,588 participants from the French NutriNet-Santé study finds in a 9.1 year follow-up that, compared with non-consumers, higher consumers of artificial sweeteners had higher risks of developing type-2 diabetes. Positive associations were also observed for individual artificial sweeteners aspartame, acesulfame-K and sucralose.

Aspartame breaks down in part into phenylalanine, which interferes with the action of an enzyme intestinal alkaline phosphatase (IAP) previously shown to prevent metabolic syndrome (a group of symptoms associated with type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease) according to a 2017 study in Applied Physiology, Nutrition and Metabolism. In this study, mice receiving aspartame in their drinking water gained more weight and developed other symptoms of metabolic syndrome than animals fed similar diets lacking aspartame. The study concludes, “IAP’s protective effects in regard to the metabolic syndrome may be inhibited by phenylalanine, a metabolite of aspartame, perhaps explaining the lack of expected weight loss and metabolic improvements associated with diet drinks.”

- Aspartame may prevent, not promote, weight loss by blocking intestinal enzyme’s activity, Massachusetts General Hospital press release (11.22.2016)

People who regularly consume artificial sweeteners are at increased risk of “excessive weight gain, metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease,” according to a 2013 Purdue review over 40 years published in Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism.

In a study that followed 66,118 women over 14 years, both sugar-sweetened beverages and artificially sweetened beverages were associated with risk of Type 2 diabetes. “Strong positive trends in T2D risk were also observed across quartiles of consumption for both types of beverage … No association was observed for 100% fruit juice consumption,” reported the 2013 study published in American Journal of Clinical Nutrition.

Intestinal dysbiosis, metabolic derangement and obesity

A 2022 study in Frontiers in Nutrition found that maternal consumption of aspartame and stevia influences the gut microbiota of offspring.”Consumption of low-dose aspartame and stevia showed limited influence on the overall structure of cecal microbiota in dams but significantly altered cecal microbiota of their 3-week old offspring.”

Artificial sweeteners can induce glucose intolerance by altering the gut microbiota, according to a 2014 study in Nature. The researchers wrote, “our results link NAS [non-caloric artificial sweetener] consumption, dysbiosis and metabolic abnormalities, thereby calling for a reassessment of massive NAS usage … Our findings suggest that NAS may have directly contributed to enhancing the exact epidemic [obesity] that they themselves were intended to fight.”

- Artificial Sweeteners May Change our Gut Bacteria in Dangerous Ways, by Ellen Ruppel Shell, Scientific American (4.1.2015)

A 2016 study in Applied Physiology Nutrition and Metabolism reported, “Aspartame intake significantly influenced the association between body mass index (BMI) and glucose tolerance… consumption of aspartame is associated with greater obesity-related impairments in glucose tolerance.”

According to a 2014 rat study in PLOS ONE, “aspartame elevated fasting glucose levels and an insulin tolerance test showed aspartame to impair insulin-stimulated glucose disposal … Fecal analysis of gut bacterial composition showed aspartame to increase total bacteria…”

Pregnancy abnormalities: Pre-term birth

According to a 2010 cohort study of 59,334 Danish pregnant women published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, “There was an association between intake of artificially sweetened carbonated and noncarbonated soft drinks and an increased risk of preterm delivery.” The study concluded, “Daily intake of artificially sweetened soft drinks may increase the risk of preterm delivery.”

- Downing Diet Soda Tied to Premature Birth, by Anne Harding, Reuters (7.23.2010)

Overweight babies

Artificially sweetened beverage consumption during pregnancy is linked to higher body mass index for babies, according to a 2016 study in JAMA Pediatrics. “To our knowledge, we provide the first human evidence that maternal consumption of artificial sweeteners during pregnancy may influence infant BMI,” the researchers wrote.

- Diet Soda in Pregnancy is Linked to Overweight Babies, by Nicholas Bakalar, New York Times (5.11.2016)

Early menarche

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Growth and Health Study followed 1988 girls for 10 years to examine prospective associations between consumption of caffeinated and noncaffeinated sugar- and artificially sweetened soft drinks and early menarche. “Consumption of caffeinated and artificially sweetened soft drinks was positively associated with risk of early menarche in a US cohort of African American and Caucasian girls,” concluded the study published in 2015 in Journal of American Clinical Nutrition.

Sperm damage

“A significant decrease in sperm function of aspartame treated animals was observed when compared with the control and MTX control,” according to a 2017 study in the International Journal of Impotence Research. “… These findings demonstrate that aspartame metabolites could be a contributing factor for development of oxidative stress in the epididymal sperm.”

Liver damage and glutathione depletion

A mouse study published in 2017 in Redox Biology reported, “Chronic administration of aspartame … caused liver injury as well as marked decreased hepatic levels of reduced glutathione, oxidized glutathione, γ-glutamylcysteine, and most metabolites of the trans-sulphuration pathway…”

A rat study published in 2017 in Nutrition Research found that, “Subchronic intake of soft drink or aspartame substantially induced hyperglycemia and hypertriacylglycerolemia… Several cytoarchitecture alterations were detected in the liver, including degeneration, infiltration, necrosis, and fibrosis, predominantly with aspartame. These data suggest that long-term intake of soft drink or aspartame-induced hepatic damage may be mediated by the induction of hyperglycemia, lipid accumulation, and oxidative stress with the involvement of adipocytokines.”

Parkinson’s disease

A July 2023 study in Nutritional Neuroscience assessed the current evidence regarding the associated physiological and cognitive effects of aspartame (APM) consumption and Parkinson’s Disease (PD). “Multiple studies demonstrated decreased brain dopamine, decreased brain norepinephrine, increased oxidative stress, increased lipid peroxidation, and decreased memory function in rodents after APM use.”

Kidney function decline

Consumption of more than two servings a day of artificially sweetened soda “is associated with a 2-fold increased odds for kidney function decline in women,” according to a 2011 study in the Clinical Journal of American Society of Nephrology.

Caution for vulnerable populations

A 2016 literature review on artificial sweeteners in the Indian Journal of Pharmacology reported, “there is inconclusive evidence to support most of their uses and some recent studies even hint that these earlier established benefits … might not be true.” Susceptible populations such as pregnant and lactating women, children, diabetics, migraine, and epilepsy patients “should use these products with utmost caution.”

Review studies on non-sugar sweeteners

Two review studies published in 2023 raised health concerns about the class of non-sugar sweeteners, which include acesulfame K, aspartame, advantame, cyclamates, neotame, saccharin, sucralose and stevia.

In May 2023, the World Health Organization advised people not to consume non-sugar sweeteners, including aspartame, for weight loss. The recommendation is based on the agency’s systematic review of the most current scientific evidence that consumption of non-sugar sweeteners is associated with increased risk of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases and all-cause mortality, as well as weight gain.

- “Replacing free sugars with NSS does not help with weight control in the long term. People need to consider other ways to reduce free sugars intake, such as consuming food with naturally occurring sugars, like fruit, or unsweetened food and beverages,” Francesco Branca, WHO Director for Nutrition and Food Safety, said in a press release. “People should reduce the sweetness of the diet altogether, starting early in life, to improve their health.”

A separate review published in May 2023 in Advances in Nutrition includes data of 11 meta-analyses obtained from 7 systematic reviews (51 cohort studies and 4 case-control studies). The review reports that artificially sweetened beverages are “associated with higher risk of obesity, type II diabetes, all-cause mortality, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease incidence (supported by highly suggestive evidence).”

Industry studies and flaws in EFSA assessment

In a July 2019 paper in the Archives of Public Health, researchers at the University of Sussex provided a detailed analysis of the EFSA’s 2013 safety assessment of aspartame and found that the panel discounted as unreliable every one of 73 studies that indicated harm, and used far more lax criteria to accept as reliable 84% of studies that found no evidence of harm.”Given the shortcomings of EFSA’s risk assessment of aspartame, and the shortcomings of all previous official toxicological risk assessments of aspartame, it would be premature to conclude that it is acceptably safe,” the study concluded.

See EFSA’s response and a follow up by researchers Erik Paul Millstone and Elizabeth Dawson in the Archives of Public Health, Why did EFSA to reduce its ADI for aspartame or recommend its use should no longer be permitted?

In his analysis of studies on aspartame, Millstone found: “About 90% of the reassuring studies were funded by large chemical corporations that manufacture and sell aspartame,” he told the BBC Panorama in 2023. “There’s a pattern there that suggests the industry designs and conducts studies that provide reassuring evidence. I saw that as an expression of a very profound and dangerous bias.”

- World’s most popular artificial sweetener must be banned, say experts New Food Magazine (11.11.2020)

- ‘Sales of aspartame should be suspended’: EFSA accused of bias in safety assessment, by Katy Askew, Food Navigator (7.27.2019)

Industry PR efforts and front groups

From the start, G.D. Searle (later Monsanto and the NutraSweet Company) deployed aggressive PR tactics to market aspartame as a safe product and deny aspartame health effects. In October 1987, Gregory Gordon reported in UPI:

“The NutraSweet Co. also has paid up to $3 million a year for a 100-person public relations effort by the Chicago offices of Burson Marsteller, a former employee of the New York PR firm said. The employee said Burson Marsteller has hired numerous scientists and physicians, often at $1,000 a day, to defend the sweetener in media interviews and other public forums. Burson Marsteller declines to discuss such matters.”

Recent reporting based on internal industry documents reveals how beverage companies such as Coca-Cola also pay third party messengers, including doctors and scientists, to promote their products and shift the blame when science ties their products to serious health problems.

See reporting by Anahad O’Connor in the New York Times, Candice Choi in the Associated Press, and findings from the U.S. Right to Know investigation on sugar industry propaganda and lobbying. Gary Ruskin of U.S. Right to Know has also co-authored a series of peer-reviewed academic papers, based on industry documents obtained by USRTK, about how Coca-Cola and its front groups influence public health conferences, journalists and health policies around the world.

News articles about soda industry PR campaigns:

- Coca-Cola’s Secret Influence on Medical and Science Journalists, by Paul Thacker, BMJ (4.5.2017) and author’s note

- If Soda Companies Don’t Want to Be Treated Like Tobacco Companies, They Need To Stop Acting Like Them, by Patrick Mustain, Scientific American (10.19.2016)

- Critic of artificial sweeteners pilloried by industry-backed scientists, by Chris Young, Center for Public Integrity (8.6.2014)

Investigative articles about aspartame dangers:

- The Story of How Fake Sugar Got Approved is Scary As Hell; It involves Donald Rumsfeld, by Kristin Wartman Lawless, Vice (4.19.2017)

- The Lowdown on Sweet? by Melanie Warner, New York Times (2.12.2006)

- NutraSweet Controversy Swirls, by Gregory Gordon, UPI series (10.1987)

Scientific references

Charlotte Debras, et al.”Artificial sweeteners and cancer risk: Results from the NutriNet-Santé population-based cohort study.” PLOS Medicine. Published: March 24, 2022 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003950

Soffritti M, Belpoggi F, Degli Esposti D, Lambertini L, Tibaldi E, Rigano A. “First experimental demonstration of the multipotential carcinogenic effects of aspartame administered in the feed to Sprague-Dawley rats.” Environ Health Perspect. 2006 Mar;114(3):379-85. PMID: 16507461. (article)

Soffritti M, Belpoggi F, Tibaldi E, Esposti DD, Lauriola M. “Life-span exposure to low doses of aspartame beginning during prenatal life increases cancer effects in rats.” Environ Health Perspect. 2007 Sep;115(9):1293-7. PMID: 17805418. (article)

Soffritti M et al. “Aspartame administered in feed, beginning prenatally through life span, induces cancers of the liver and lung in male Swiss mice.” Am J Ind Med. 2010 Dec; 53(12):1197-206. PMID: 20886530. (abstract / article)

Schernhammer ES, Bertrand KA, Birmann BM, Sampson L, Willett WC, Feskanich D., “Consumption of artificial sweetener– and sugar-containing soda and risk of lymphoma and leukemia in men and women.” Am J Clin Nutr. 2012 Dec;96(6):1419-28. PMID: 23097267. (abstract / article)

Soffritti M1, Padovani M, Tibaldi E, Falcioni L, Manservisi F, Belpoggi F., “The carcinogenic effects of aspartame: The urgent need for regulatory re-evaluation.” Am J Ind Med. 2014 Apr;57(4):383-97. doi: 10.1002/ajim.22296. Epub 2014 Jan 16. (abstract / article)

Olney JW, Farber NB, Spitznagel E, Robins LN. “Increasing brain tumor rates: is there a link to aspartame?” J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1996 Nov;55(11):1115-23. PMID: 8939194. (abstract)

Azad, Meghan B., et al.”Nonnutritive sweeteners and cardiometabolic health: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials and prospective cohort studies.”CMAJJuly 17, 2017vol. 189no. 28doi:10.1503/cmaj.161390 (abstract / article)

Fowler SP. Low-calorie sweetener use and energy balance: Results from experimental studies in animals, and large-scale prospective studies in humans. Physiol Behav. 2016 Oct 1;164(Pt B):517-23. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2016.04.047. Epub 2016 Apr 26. (abstract)

Vyas A et al. “Diet Drink Consumption And The Risk of Cardiovascular Events: A Report from The Women’s Health Initiative.” J Gen Intern Med.2015 Apr;30(4):462-8. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-3098-0. Epub 2014 Dec 17. (abstract / article)

Matthew P. Pase, PhD; Jayandra J. Himali, PhD; Alexa S. Beiser, PhD; Hugo J. Aparicio, MD; Claudia L. Satizabal, PhD; Ramachandran S. Vasan, MD; Sudha Seshadri, MD; Paul F. Jacques, DSc. “Sugar and Artificially Sweetened Beverages and the Risks of Incident Stroke and Dementia. A Prospective Cohort Study.” Stroke. 2017 April; STROKEAHA.116.016027 (abstract / article)

Yang M et al. “Alzheimer’s Disease and Methanol Toxicity (Part 1): Chronic Methanol Feeding Led to Memory Impairments and Tau Hyperphosphorylation in Mice.” J Alzheimers Dis. 2014 Apr 30. (abstract)

Yang M et al. “Alzheimer’s Disease and Methanol Toxicity (Part 2): Lessons from Four Rhesus Macaques (Macaca mulatta) Chronically Fed Methanol.” J Alzheimers Dis. 2014 Apr 30. (abstract)

Camfield PR, Camfield CS, Dooley JM, Gordon K, Jollymore S, Weaver DF. “Aspartame exacerbates EEG spike-wave discharge in children with generalized absence epilepsy: a double-blind controlled study.” Neurology. 1992 May;42(5):1000-3. PMID: 1579221. (abstract)

Maher TJ, Wurtman RJ. “Possible neurologic effects of aspartame, a widely used food additive.” Environ Health Perspect. 1987 Nov; 75:53-7. PMID: 3319565. (abstract / article)

Wurtman RJ. “Aspartame: possible effect on seizure susceptibility.” Lancet. 1985 Nov 9;2(8463):1060. PMID: 2865529. ( abstract)

Choudhary AK, Lee YY. “Neurophysiological symptoms and aspartame: What is the connection?” Nutr Neurosci, 2017 Feb 15:1-11. doi: 10.1080/1028415X.2017.1288340. (abstract)

Onaolapo AY, Onaolapo OJ, Nwoha PU. “Aspartame and the hippocampus: Revealing a bi-directional, dose/time-dependent behavioural and morphological shift in mice.” Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2017 Mar;139:76-88. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2016.12.021. Epub 2016 Dec 31. (abstract)

Humphries P, Pretorius E, Naudé H. “Direct and indirect cellular effects of aspartame on the brain.” Eur J Clin Nutr. 2008 Apr;62(4):451-62. (abstract / article)

Tsakiris S, Giannoulia-Karantana A, Simintzi I, Schulpis KH. “The effect of aspartame metabolites on human erythrocyte membrane acetylcholinesterase activity.” Pharmacol Res. 2006 Jan;53(1):1-5. PMID: 16129618. (abstract)

Park CH et al. “Glutamate and aspartate impair memory retention and damage hypothalamic neurons in adult mice.” Toxicol Lett. 2000 May 19;115(2):117-25. PMID: 10802387. (abstract)

Walton RG, Hudak R, Green-Waite R. “Adverse reactions to aspartame: double-blind challenge in patients from a vulnerable population.” J. Biol Psychiatry. 1993 Jul 1-15;34(1-2):13-7. PMID: 8373935. (abstract / article)

Yokogoshi H, Roberts CH, Caballero B, Wurtman RJ. “Effects of aspartame and glucose administration on brain and plasma levels of large neutral amino acids and brain 5-hydroxyindoles.” Am J Clin Nutr. 1984 Jul;40(1):1-7. PMID: 6204522. (abstract)

Olney JW, Ho OL. “Brain Damage in Infant Mice Following Oral Intake of Glutamate, Aspartate or Cysteine.” Nature. 1970 Aug 8;227(5258):609-11. PMID: 5464249. (abstract) Blumenthal HJ, Vance DA. “Chewing gum headaches.” Headache. 1997 Nov-Dec; 37(10):665-6. PMID: 9439090. (abstract / article)

Van den Eeden SK, Koepsell TD, Longstreth WT Jr, van Belle G, Daling JR, McKnight B. “Aspartame ingestion and headaches: a randomized crossover trial.” Neurology. 1994 Oct;44(10):1787-93. PMID: 7936222. (abstract)

Lipton RB, Newman LC, Cohen JS, Solomon S. “Aspartame as a dietary trigger of headache.” Headache. 1989 Feb;29(2):90-2. PMID: 2708042. (abstract)

Koehler SM, Glaros A. “The effect of aspartame on migraine headache.” Headache. 1988 Feb;28(1):10-4. PMID: 3277925. (abstract)

Julie Lin and Gary C. Curhan. “Associations of Sugar and Artificially Sweetened Soda with Albuminuria and Kidney Function Decline in Women.” Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011 Jan; 6(1): 160–166. (abstract / article)

Gul SS, Hamilton AR, Munoz AR, Phupitakphol T, Liu W, Hyoju SK, Economopoulos KP, Morrison S, Hu D, Zhang W, Gharedaghi MH, Huo H, Hamarneh SR, Hodin RA. “Inhibition of the gut enzyme intestinal alkaline phosphatase may explain how aspartame promotes glucose intolerance and obesity in mice.” Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2017 Jan;42(1):77-83. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2016-0346. Epub 2016 Nov 18. (abstract / article)

Susan E. Swithers, “Artificial sweeteners produce the counterintuitive effect of inducing metabolic derangements.” Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2013 Sep; 24(9): 431–441. (article)

Guy Fagherazzi, A Vilier, D Saes Sartorelli, M Lajous, B Balkau, F Clavel-Chapelon. “Consumption of artificially and sugar-sweetened beverages and incident type 2 diabetes in the Etude Epidémiologique auprès des femmes de la Mutuelle Générale de l’Education Nationale–European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition cohort.” Am J Clin Nutr. 2013, Jan 30; doi: 10.3945/ ajcn.112.050997 ajcn.050997. (abstract / article)

Weilan Wang et al., “A Metagenomics Investigation of Intergenerational Effects of Non-nutritive Sweeteners on Gut Microbiome.” Front. Nutr., 14 January 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2021.795848

Suez J et al. “Artificial sweeteners induce glucose intolerance by altering the gut microbiota.” Nature. 2014 Oct 9;514(7521). PMID: 25231862. (abstract / article)

Kuk JL, Brown RE. “Aspartame intake is associated with greater glucose intolerance in individuals with obesity.” Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2016 Jul;41(7):795-8. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2015-0675. Epub 2016 May 24. (abstract)

Palmnäs MSA, Cowan TE, Bomhof MR, Su J, Reimer RA, Vogel HJ, et al. (2014) Low-Dose Aspartame Consumption Differentially Affects Gut Microbiota-Host Metabolic Interactions in the Diet-Induced Obese Rat. PLoS ONE 9(10): e109841. (article)

Halldorsson TI, Strøm M, Petersen SB, Olsen SF. “Intake of artificially sweetened soft drinks and risk of preterm delivery: a prospective cohort study in 59,334 Danish pregnant women.” Am J Clin Nutr. 2010 Sep;92(3):626-33. PMID: 20592133. (abstract / article)

Meghan B.Azad, PhD; Atul K.Sharma, MSc, MD; Russell J.de Souza, RD, ScD; et al. “Association Between Artificially Sweetened Beverage Consumption During Pregnancy and Infant Body Mass Index.” JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(7):662-670. (abstract)

Mueller NT, Jacobs DR Jr, MacLehose RF, Demerath EW, Kelly SP, Dreyfus JG, Pereira MA. “Consumption of caffeinated and artificially sweetened soft drinks is associated with risk of early menarche.” Am J Clin Nutr. 2015 Sep;102(3):648-54. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.114.100958. Epub 2015 Jul 15. (abstract)

Ashok I, Poornima PS, Wankhar D, Ravindran R, Sheeladevi R. “Oxidative stress evoked damages on rat sperm and attenuated antioxidant status on consumption of aspartame.” Int J Impot Res. 2017 Apr 27. doi: 10.1038/ijir.2017.17. (abstract / article)

Finamor I, Pérez S, Bressan CA, Brenner CE, Rius-Pérez S, Brittes PC, Cheiran G, Rocha MI, da Veiga M, Sastre J, Pavanato MA., “Chronic aspartame intake causes changes in the trans-sulphuration pathway, glutathione depletion and liver damage in mice.” Redox Biol. 2017 Apr;11:701-707. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2017.01.019. Epub 2017 Feb 1. (abstract / article)

Lebda MA, Tohamy HG, El-Sayed YS. “Long-term soft drink and aspartame intake induces hepatic damage via dysregulation of adipocytokines and alteration of the lipid profile and antioxidant status.” Nutr Res. 2017 Apr 19. pii: S0271-5317(17)30096-9. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2017.04.002. [Epub ahead of print] (abstract)

Sharma A, Amarnath S, Thulasimani M, Ramaswamy S. “Artificial sweeteners as a sugar substitute: Are they really safe?” Indian J Pharmacol 2016;48:237-40 (article)