A research contract gave multinational pesticide manufacturers ample influence over pesticide research conducted at a state university.

Experts in research ethics found fault with the influence the contract gave the funders, and linked the situation to broader transparency failures in corporate-funded research.

Resulting scientific studies only acknowledged the funds the pesticide manufacturers contributed to the project, despite the contract granting them influence over the study methods. University researchers say this is because the pesticide manufacturers’ involvement was less than what was outlined in the contract.

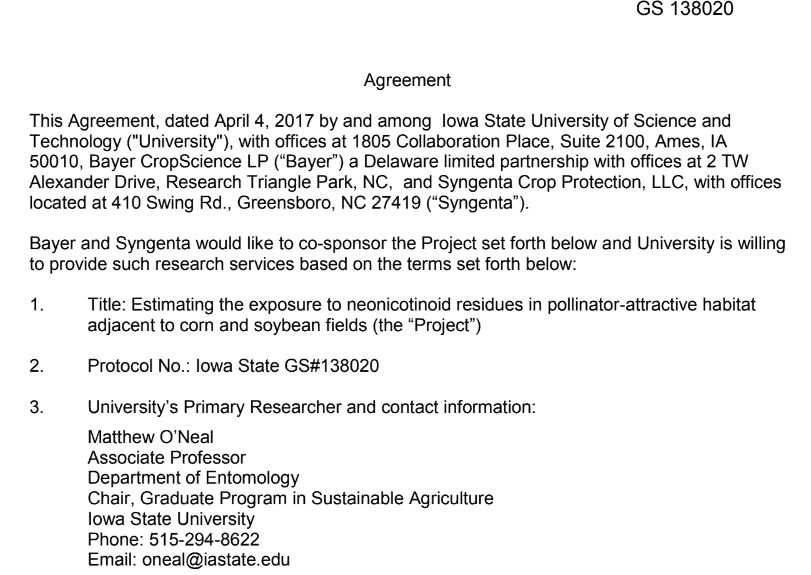

In 2017, Bayer and Syngenta, two companies that manufacture neonicotinoid insecticides, gave $301,671 to Iowa State University (ISU) researchers for a project titled “Estimating the exposure to neonicotinoid residues in pollinator-attractive habitat adjacent to corn and soybean fields.”

Neonicotinoids, or neonics, are one of the most commonly used insecticides in the world, and are toxic to bees and other pollinators. They are systemic insecticides, which means a plant can absorb and distribute them throughout all its parts.

When the ISU researchers proposed this research, they cited existing evidence that neonics from crop fields wind up in nearby flowers, whether they are weeds or intentionally-planted pollinator refuges.

The research contract sought to answer whether the neonic levels in pollinator plantings, or “prairie strips ”, next to crop fields were high enough to hurt pollinators. One impetus for the study was to determine whether those plantings could harm bees and butterflies by luring them to pesticide-contaminated food. Another was to assess whether it was necessary to maintain a 125-foot pesticide-free buffer around monarch butterfly breeding habitat, according to the contract.

The contract was prepared after the funders and ISU faculty discussed their shared study interests during the 2016 International Congress of Entomology, ISU News Service Director Angie Hunt said. Hunt said she was speaking on behalf of Matthew O’Neal, Joel Coats, and Steve Bradbury, all ISU faculty listed as study personnel funded by the contract.

“Those conversations led to Iowa State’s development of a research proposal to measure exposure in prairie strips, as the strips provided a location where neonics and bees would likely be found,” Hunt said. Bayer and Syngenta didn’t write the contract’s statement of work, she said:

“Iowa State University researchers drafted the statement of work; it was not a collaborative effort [with the funders].”

What the research contract allows Bayer to do

The contract let Bayer advise on the study’s methods and for its employee to assist on the “design, conduct, and interpretation of the study.”

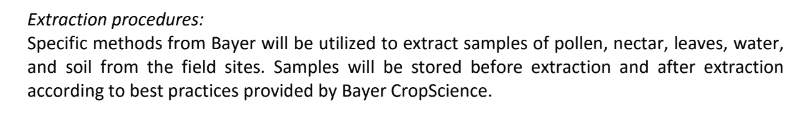

“Specific methods from Bayer will be utilized to extract samples of pollen, nectar, leaves, water, and soil from the field sites,” the contract stated. “Samples will be stored before extraction and after extraction according to best practices provided by Bayer CropScience.”

The methods also said that “ISU and Bayer will work together” prior to analyzing neonicotinoid residues on any samples “to select standards and receive training for the Toxicology graduate student regarding analytical methods.”

The contract empowered Bayer scientist Dan Schmehl to assist with the “design, conduct, and interpretation of the study.” Bayer employee Michael McCarville was slated to “interface with growers participating in the study.”

The contract also said that Bayer may sample farmer participant seeds, provide transit stability samples to ensure the stability of relevant analytes and metabolites in pollen and nectar samples, and train two “team members” at their North American headquarters.

Furthermore, the contract required ISU to give Bayer and Syngenta 30 days to review and comment on all prospective publications or presentations to determine if they contained any confidential information.

“If Bayer and Syngenta raise no objection within the notification period above,” then ISU could proceed, according to the contract. It also required ISU to obtain the funders’ permission before accepting federal funding or otherwise involving a federal agency in the project.

Experts flag Bayer’s control over the research

“This isn’t really an independent university study,” -Lisa Bero

Experts say the contract gave Bayer a level of control over the research that they expected to be disclosed in the final publication. “What’s interesting here to me is, this isn’t really an independent university study because we’ve got two Bayer employees who are actually on the project. So, this is really just a joint company project that involves some university researchers,” Lisa Bero said of the contract. Bero is a professor of medicine and public health, and a chief scientist for the Center for Bioethics and Humanities at University of Colorado.

Paul Thacker, an investigative journalist specializing in research conflicts of interest, agreed. He noted the contract puts Bayer in charge of setting the standards and methods, as well as the null values for the sampling.

“[The contract] makes these guys look like they’re a lab for hire… Bayer could have hired a contract research lab to do this exact kind of research, but then it would’ve been a Bayer study. But they didn’t want it to be a Bayer study,” he said.

Although it’s common for funders to have the right to review manuscripts prior to publication, Thacker said he interprets the contract to mean that the funders could also stop publication, quoting this provision: “If Bayer and Syngenta raise no objection within the notification period above, then University has the right to proceed with public disclosure.”

“That was very worrisome,” Thacker said. He also took issue with the clause concerning federal funding. “What if [ISU] found a problem and wanted to notify the EPA? … They can’t. It’s just weird.”

Bayer’s level of influence, as outlined in the contract, ought to justify authorship or acknowledgements in resulting publications, experts said.

“Given that Bayer scientist Dan Schmehl was listed as assisting with the ‘design, conduct, and interpretation of the study’ in the contract, I think that should have been declared in the published paper. He should probably have been listed as an author for that reason, even if he did not write any of the sentences in the final paper,” Erik Millstone said. Millstone, a professor emeritus at the University of Sussex, researches the causes and consequences of scientific and technological change in the food and agricultural sectors and has studied corporate influence on science and policy.

Bero agreed.

“They have very significant roles in the project,” she said of Bayer’s Schmehl and McCarville.

McCarville’s stated role, although smaller, is significant, she said.

“If this is analogous to a clinical trial, he’s kind of like the person enrolling patients in the trial,” Bero said. “Maybe he wouldn’t appear as an author, but he would certainly be acknowledged, as he interfaces with the growers.”

Studies referred to Bayer and Syngenta only as funders

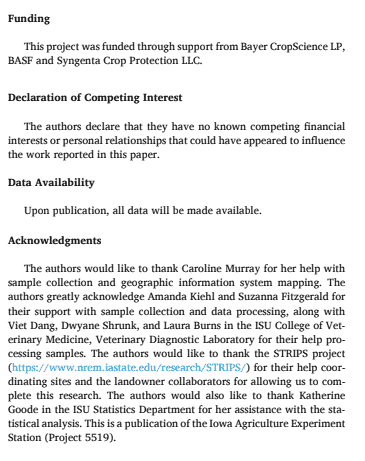

So far, the ISU team has produced two scientific publications related to the contract. Both say the work was funded by a grant from Bayer and Syngenta.

The 2020 paper in Molecules, a MDPI publication, describes a method the ISU researchers used to analyze pollen and leaf tissue samples for neonics. The paper explicitly says, “The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.”

It mentions that Bayer provided the analytical chemical standards for the analysis.

The 2022 paper, in Agriculture, Ecosystems, and the Environment, an Elsevier publication, describes the levels of various neonics they found in cropland-adjacent soil and leaf tissue, including milkweed, and determines that the levels were not high enough to hurt monarch butterfly larvae. It says the authors have “no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.”

Neither publication names Schmehl, McCarville, or any other contributions Bayer made besides funding and the analytical standards.

ISU describes Bayer’s contributions to the study

According to ISU, Bayer’s methodological and logistical contributions were less than what’s described in the contract, and that’s why neither publication mentions Bayer in any context other than funding and providing analytical samples.

“The grant lists a limited range of methodological options that could be used if considered necessary. Bayer’s contributions were limited to technical advice to ensure methods were within industry standards,” Hunt said.

What parts of the contract that cited Bayer’s involvement were utilized?

“While the Iowa State University team was informed of Bayer’s analytical chemistry and sampling techniques, the analytical method published by Hall et al. 2020 was developed solely by Hall and others at Iowa State. Sample collection and storage followed generally accepted practices,” Hunt said. “Dan Schmehl provided training on how to extract pollen and nectar from individual bees.”

Hunt said ISU was not aware of Michael McCarville interacting with any growers, despite his mention in the contract.

Bayer also provided analytical standard samples for ISU’s chemical analysis, she confirmed. But Bayer did not conduct their own analyses of farmer participants’ treated seeds, nor did ISU use the transit stability samples that Bayer provided for them, Hunt said. ISU researchers did visit Bayer’s headquarters in 2017 to present their study proposal and tour Bayer’s bee research facility, she said.

ISU said Schmehl provided training to extract pollen and nectar from bees, and advised on industry standards expected by the EPA. But U.S. Right to Know obtained an email thread from April 2018 in which O’Neal asked Schmehl whether they should include a certain site in the second year of their study, since it was using chlorantraniliprole, a non-neonic seed treatment.

Schmehl responded: “You are correct that we will not use chlorantraniliprole since this is not within scope for the methods developed to screen for the neonics.”

Schmehl then asked for the scope of the second year’s project scope and budget so Bayer could work on extending the funding agreement for another year.

“As soon as sites and scope are confirmed, I want to get our team in contact with your contract department so that we can extend our agreement from last year to a second year and get this project officially funded for you. What is the latest on corn planting? Are the sites proposed for the continuation of our study prepared for our use?” Schmehl asked the researchers.

“The email you referenced was a conversation about the scope of future work, not a request for technical contribution to the research,” Hunt said when asked why the researchers sought Schmehl’s advice on sampling sites, and what other matters he advised on.

Bayer spokesperson Kyel Richard did not respond when asked to name Schmehl’s and Bayer’s specific contributions to the methodology.

“University researchers play an invaluable role in ensuring growers can use agriculture technologies safely, sustainably, and effectively. We have a long history of working alongside and supporting university researchers – this kind of university/company collaboration is very common and important across science-based industries,” he said in a statement.

“We stand behind our work with university researchers, and as a science-based company we are committed to transparency and independence of science.

“Depending on the research project, companies can contribute to the work of university researchers in a variety of ways, including by providing resources (e.g., funding, products, equipment) or with more involved support (e.g., making nonbinding proposals for study design, data collection, data analysis). Importantly, the researchers remain in control of the project at all times, including any results. According to good scientific publication practice, it is important to us that researchers properly acknowledge our contributions in scientific publications just as they appropriately acknowledge the contributions of every other participant.”

Richard referred to Bayer’s statements on transparency. Under “Transparency for our Scientific Collaborations,” the company says they “publicly disclose new contract-based scientific collaborations with universities, public research institutions and individuals in Germany via the Bayer Science Collaboration Explorer (BSCE).”

That database “has successfully piloted in Germany, and we will include data on scientific collaborations in the United States in the near future,” Richard said.

However, there have been cases when the chemical industry has obscured the full extent of its role in scientific studies. For example, internal Monsanto documents released during litigation over the human health impacts of the glyphosate-based herbicide called Roundup, showed the company engaged in ghostwriting, or secretly authoring journal articles that were supposedly authored by academic researchers. Bayer acquired Monsanto in 2018.

Did Bayer’s role in methodology merit disclosure?

There is a discrepancy between what Bayer was contractually bound to provide, and the acknowledgement of their role in the published studies, Thacker said. “Either [ISU] violated the contract or they violated the acknowledgements. Those two things don’t match,” he said.

“No one who would pick up the studies would have any clue of Bayer’s legally acknowledged involvement.”

The contract itself, Thacker said, is a legally binding document, quoting: “University will conduct the testing in strict compliance with the Project and agrees not to deviate from the Project unless agreed by all parties. University will strictly conform to all regulations which may apply to its activities in the framework of the Project.” If ISU didn’t plan to follow the contract’s work designations, Thacker said, “why put it in there?”

MDPI conflict of interest guidelines state that authors must disclose “any personal circumstances or interest that may be perceived as influencing the representation or interpretation of reported research results,” and “Any role of the funding sponsors in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results must be declared in this section.”

MDPI’s authorship guidelines state that authorship should be granted to someone who substantially contributes to the study concept or design, or data collection, analysis or interpretation, drafts or revises the publication, approves the final version of the publication, and accepts accountability for all aspects of the work. “Those who contributed to the work but do not qualify for authorship should be listed in the acknowledgments.”

Elsevier’s guidelines require a statement on the role of the publication’s sponsors in study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation, report writing, and decision to submit the article for publication. “If the funding source(s) had no such involvement, it is recommended to state this.”

Editors for Molecules and Agriculture, Ecosystems, and Environment, as well as the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) did not return requests for comment about their conflict of interest standards.

“ISU seems to be indicating… that Bayer had a much lesser role than indicated in the contract,” Bero said. She said that it could be hard for an editor of a publication to determine whether ISU’s disclosure was adequate based on the available information.

“It is very difficult to know what the truth is,” she said.

No disclosure of concurrent grants from the same companies

Aside from the question of disclosing Bayer’s methodological contributions, the ISU researchers apparently did not disclose the other funding they were receiving concurrently from Bayer and Syngenta.

Elsevier recommends that authors declare any financial interests or relationships within the last three years related to the subject matter but not directly to the manuscript.

According to O’Neal’s CV, he received a separate $8,000 grant from Syngenta in 2019. O’Neal was also part of a Foundation for Food and Agriculture Research (FFAR) grant (2018-2021) that received matching funds from agrichemical companies, including Bayer and Syngenta. Although outside of the Elsevier publication’s three-year window, O’Neal and two colleagues also received a $539,913 grant from Monsanto between 2015 and 2018.

According to Bradbury’s CV, he was a part of the same 2018-2021 FFAR grant with matching agrichemical industry funds as O’Neal. He received $45,000 from Bayer, Syngenta, and Dupont between 2017 and 2018 to fund an IPM conference, and accepted $98,850 from Monsanto from 2018-2021 for a monarch butterfly study.

Dr. Coats has not publicly updated his CV since 2014, but Bradbury’s CV lists him on the $98,950 Monsanto grant from 2018-2021.

The grants that fell within the three year window of publication should have been disclosed, Bero said.

Millstone said the authors may have provided “all the information that was formally required by that journal, but not all the information that could be relevant, and maybe not all the information that Elsevier asserts authors should declare.”

“If they had agreed and signed other contracts, that should have been disclosed under Elsevier’s rules,” he added.

ISU said that “the authors provided the appropriate disclosures applicable to the research” when asked why they didn’t disclose Bayer’s “technical advice” contributions, or whether they notified the publishers of the other grants they received from the funders within the three-year window.

Other conflicts of interest

The potential benefits of this research to Bayer and Syngenta are visible to Thacker.

“It’s Bayer. Their job is to sell pesticides, it’s not to save butterflies,” he said.

The research questions could be interpreted as motivated by a concern for potential litigation or regulation, he said.

“Is [the research out of] concern that you’re harming butterflies, or is it concern that you’re going to get an expanded buffer or pesticide ban,” he said.

Pesticide-free buffers mean less land available for pesticide application, he noted.

Dr. Millstone said he’s observed a pattern in his work, in which industry-sponsored studies “purporting to put some industrial product or process in the clear are cunningly contrived to produce as favorable results as possible while also cunningly concealing the fact that it’s so contrived.”

“You decide what answers you want and you contrive a methodology to give you the answer you want, then you report your methodology as if that is the only sensical thing to do in the first place,” he said.

When asked whether Bayer’s role in the study constituted a conflict of interest, Hunt said that all ISU participants in the study complied with the university’s conflict of interest and commitment policy.

Further grants

Bayer awarded the ISU researchers $96,302 in April 2018, a year after the first grant was signed, to continue the sample collection and chemical analysis started in 2017. The 2018 grant had all the same stipulations involving Bayer as the 2017 grant, except it no longer referred to Bayer’s transit stability samples, or funding for training opportunities at Bayer headquarters.

In 2019, the team received a third yearlong grant of $90,000 from Syngenta and BASF to focus further on pollen and nectar collection. The 2019 grant does not mention any methodological contributions from the funders.

A future manuscript from the ISU team will analyze “pollen and nectar collected by bees (A. mellifera and Bombus spp.) within these prairie strips” for neonics, according to the group’s 2022 Agriculture, Ecosystems, and Environment paper.

This work’s relation to broader patterns of corporate-funded research

“Why on earth did the companies bother to go to the university academics and ask them to do the work rather than simply doing it themselves?” Millstone asked. “They’ve got the technological capability, in fact, in some respects they’ve got more technology and resources than the academics have.”

“I think the companies Bayer and Syngenta were funding this to try to give an illusion of independence and objectivity to the study.” -Erik Millstone

“I think the companies Bayer and Syngenta were funding this to try to give an illusion of independence and objectivity to the study,” Millstone said.

What does it mean for academic literature when corporate influence or conflicts of interest are not adequately disclosed?

“Corporate sponsors want to guide the selection of questions that researchers study, and then they try to influence which data are collected, how those data are interpreted, and which conclusions are reached,” Millstone said.

“Having invested in generating reassuring narratives about their products, those studies are fed into policy-making institutions, like the FDA and EPA,” he said, while corporations are also influencing those agencies’ scientists, as well as the policymakers regulating their products.

“The net result is a regime in which the protection of public and environmental health is compromised and undermined to benefit corporate and commercial interests.”

U.S. Right to Know obtained the documents for this report through an Iowa Open Records Law request to Iowa State University.

Abbe Hamilton is an investigative reporter covering neonicotinoid science and policy for U.S. Right to Know.

Documents referenced in this piece include:

The 2017 contract between Bayer, Syngenta, and ISU

ISU’s 2020 paper in Molecules

ISU’s 2022 Agriculture, Ecosystems, and Environment paper

Matching funds documents from a Foundation for Food and Agriculture Research grant to researchers including O’Neal and Bradbury that ran 2018-2021

A 2018 email thread between Bayer’s Dan Schmehl and Matt O’Neal