“USRTK’s plan [to FOIA universities] will impact the entire industry.”

Monsanto memo

The following is an excerpt from Merchants of Poison: How Monsanto Sold the World on a Toxic Pesticide by Stacy Malkan, with Kendra Klein, PhD and Anna Lappé (you can read the full report here). The analysis draws from thousands of pages of internal corporate documents released during lawsuits brought by people suing Monsanto over allegations that exposure to glyphosate-based Roundup caused them to develop cancer; and many more obtained through a years-long public records investigation by U.S. Right to Know. We report on 5 tactics in the Monsanto-led PR campaign to defend glyphosate and the GMO seeds designed to tolerate the chemical. Here, we discuss what the documents reveal about how academics and universities played a key role in Monsanto’s PR and product-defense efforts.

See also: Tactic 1: Manipulating Science

Tactic 2: Co-opting Academia

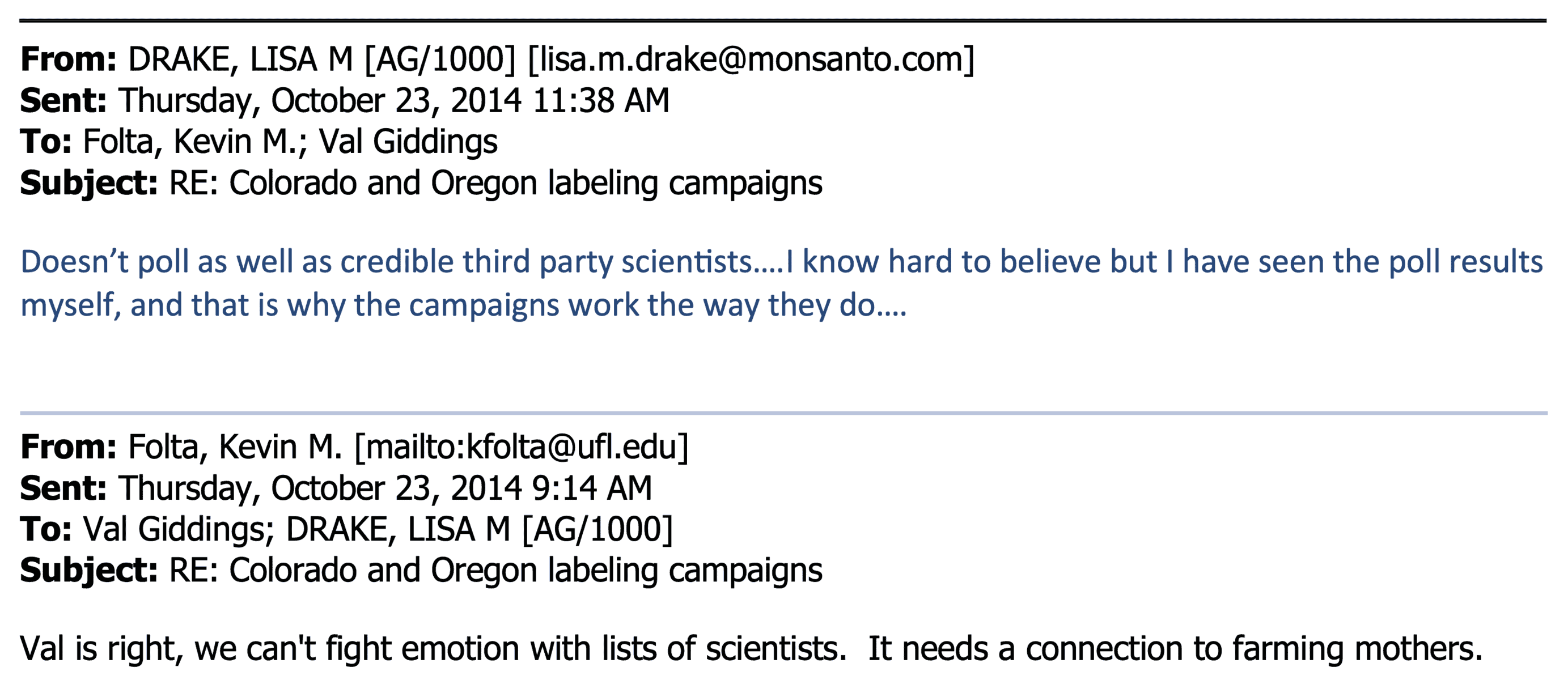

In the fall of 2014, as voters in Oregon and Washington were poised to vote on whether genetically engineered foods should be labeled, industry allies grew worried about Monsanto’s plan to feature scientists in ads for the anti-labeling campaign. “I’m a little skeptical that a letter with a lot of scientist signatures will be enough to counter the flood of fear mongering,” Val Giddings, the former vice president of the biotechnology trade association, wrote to Monsanto’s Lisa Drake.[1] Giddings suggested the company instead consider creating “TV spots featuring attractive young women, preferably mommy farmers” to persuade voters to vote against labeling requirements. Drake shot down that idea: “Doesn’t poll as well as credible third party scientists,” she told Giddings. “I know [it is] hard to believe but I have seen the poll results myself … and that is why the campaigns work the way they do.”[2]

Monsanto’s PR helpers strategize about how to defeat GMO labeling:

_____

Indeed, the “voices of authority” — especially academic experts — receive the highest marks on trust, according to global surveys.[3] In this context, the growing private-sector influence over universities, and land grant institutions in particular, is concerning. From 1970 to 2014, public funding to land grant universities for agricultural research and development grew by just 20 percent, while private funding grew by 193 percent to $6.3 billion, according to an analysis from the Agricultural Policy Analysis Center.[4] Today, hundreds of millions of dollars flow from agribusiness, including pesticide companies, into land grant universities in the United States. This funding is used to sponsor buildings, [5] endow professorships and pay for research, according to an analysis from the public interest group Food and Water Watch.[6] “The influence this money purchases is enormous,” the Food and Water Watch analysis concluded. “Corporate money shifts the public research agenda toward the ambitions of the private sector, whose profit motivations are often at odds with the public good.”

The tobacco industry and fossil fuel industry have long recognized the benefits of working with academics and influencing academic agendas through institutional funding. We now have ample evidence of how Monsanto, too, has influenced academic institutions and enlisted academics in its campaign to shape consensus on the safety of glyphosate and crops genetically engineered to tolerate the chemical.

How much money did Monsanto and other pesticide companies give to land grant universities and to individual professors? What benefits do corporate donors get in return for these investments? And why is so much of this information hidden from the public? These are some of the questions that prompted Gary Ruskin at U.S. Right to Know (USRTK) to launch an investigation in 2015, using the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) and state public record laws to research how Monsanto and other pesticide firms work with and pay academics. In the years since, USRTK has obtained and reported on thousands of industry and government documents, many of which are now posted in the USRTK collections in the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Food and Chemical Industry Document Libraries.[7]

The documents shed light on how food and chemical corporations rely on many third-party allies, including academics, to promote their products. They also make clear that inquiries into the ties between industry and academia were questions that Monsanto and other pesticide companies wanted to avoid answering.

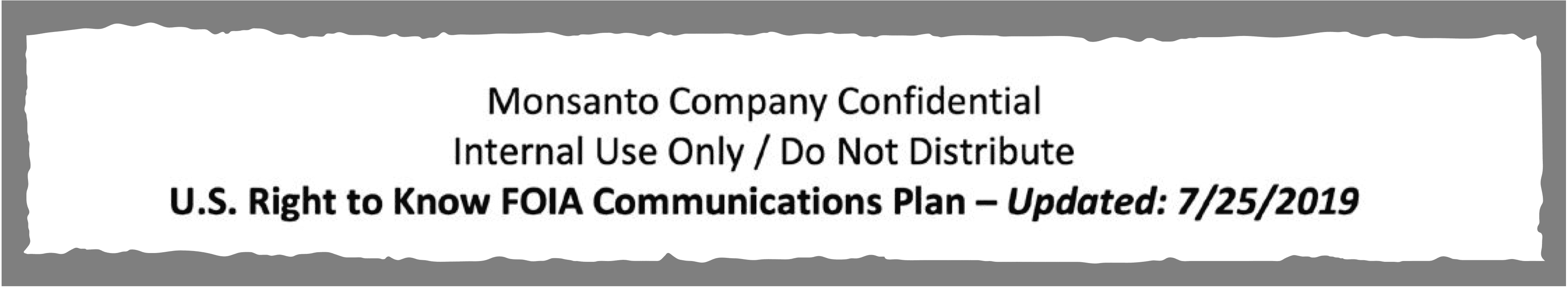

Fighting transparency at public universities

A confidential Monsanto memo dated July 2019 noted: “USRTK’s plan [to FOIA universities] will impact the entire industry” and “has the potential to be extremely damaging.”[8] The 31-page memo details Monsanto’s plan to form a coordinated defense to counter the public record requests — involving PR firms, trade groups, 11 Monsanto employees, and academic allies — to protect Monsanto’s reputation and what the company dubbed “freedom to operate” or FTO, and to protect its relationships with academics.

The memo gives guidance to employees on how to avoid disclosing details about funding while conveying “complete transparency in our relationship with academics.” Sample questions and suggested answers are offered along with additional action items like: “Brainstorm more; especially funding options like unrestricted grants.” In response to the sample question: “Should we have been more transparent about payment for travel for the academics/financing these scholars?” the Monsanto memo directs employees to explain: “We follow the guidance for gifts, grants, research agreements, etc. that is provided by the universities that we fund.” [9]

One way universities can receive corporate donations without transparency is via university foundations, which are not required to disclose their donors. In the case of the University of Florida Foundation, there was specific guidance for how to answer questions about donations. If asked whether Monsanto was a “gold donor” to the foundation, for example, the company document suggested this answer: “I have not been able to secure information to address your mention of Monsanto as a ‘gold donor.’” The company was a gold donor — a fact that had already been reported by the New York Times in 2015.[10]

Undisclosed partnerships with academics and universities

The FOIA research turned up a number of examples of how Monsanto relied on academics to shape the narrative about its products and help keep them unregulated. In 2015, Pulitzer-Prize winning journalist Eric Lipton reported on this influence in a front-page New York Times article: “Food industry enlisted academics in GMO labeling war, emails show.”[11] The article reports on internal company documents, first obtained by U.S. Right to Know, showing how Monsanto paid academics to promote genetically engineered foods in an effort to keep these products unlabeled and unregulated. Monsanto relied on academics, Lipton reported, “for the gloss of impartiality and weight of authority that come with a professor’s pedigree.”[12]

_____

“Professors/researchers/scientists have a big white hat in this debate.”

Bill Mashek, Ketchum PR

_____

As one example, Monsanto gave a $25,000 grant to University of Florida Professor Kevin Folta to run promotional programs for GMOs[13] , even as Folta publicly claimed to have no ties to Monsanto.[14] [15] The programs involved Folta traveling to other universities to train students and academics on how to promote GMOs and argue that they should not be labeled. (After the Monsanto funding became public, Folta donated the money to a food bank, but he continued receiving money from pesticide companies without full disclosure about his sources of industry funding.)[16]

In documents reported by the New York Times, the pesticide industry’s PR firm Ketchum was clear how valuable Folta, and academics more broadly, have been for the industry’s public relations: “Professors/researchers/scientists have a big white hat in this debate and support in their states, from politicians to producers,” Bill Mashek, a vice president at Ketchum, wrote to Folta in 2014. “Keep it up!”[17]

In 2015, Monsanto’s Lisa Drake engaged Folta to help boost the profile of GMOs on WebMD, a website that Vox characterized as the “most popular source of health information in the United States.”[18] “Over the past six months,” Drake wrote to Folta, “we have worked hard through third parties to insert fresh and current material on WebMD relating to biotechnology health and safety.” Before that effort, she said, “the material popping up” about the topic “dredged up highly negative input from Organic Consumer Association and the anti-GMO critics.” While Drake noted that recent pieces that had been placed by third parties had “improved the search results somewhat,” she was seeking Folta’s support to do more: “It is a fairly simple process,” she said, and asked Folta to consider, “submitting a blog on the safety and health of biotech,” and gave him instructions for how to do so. Folta’s response: “Can do! My pleasure.”[19]

Monsanto’s influence with academia doesn’t simply run through individual professors. The University of Florida Foundation has also received significant funds from pesticide and seed companies — more than $12 million for the 2013-14 academic year, including a $1 million grant from “gold donor” Monsanto.[20] The University of Florida, in turn, has been a stalwart ally in communicating industry-friendly messaging. In a 2014 email to Monsanto, Professor David Clark, from the university’s Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences Plant Innovation Program (IFAS) described how the institution’s “stance” on GMOs is “harmonious” with Monsanto’s.[21] As an example of this harmonious messaging, Clark shared a video of Jack Payne, IFAS senior vice president, stating, “there is no science that agrees with these folks that are afraid of GMOs.”[22]

_____

“I thought your talk was excellent … and it is harmonious with the stance we are taking on GMOs at the University of Florida.”

University of Florida IFAS Director David Clark to Monsanto’s Robb Fraley

_____

Clark also noted that both Jack Payne, UF’s senior vice president for agriculture and natural resources, and Kevin Folta were “ramping up their efforts to spread the good word.” He added: “Kevin is our lead spokesperson at UF on the GMO topic and he has taken on the charge of doing just what we discussed — educating the masses.” [23] In that role, Folta has mounted a passionate defense of pesticides. On his “Talking Biotech” podcast, Folta has claimed that the health risk of consuming pesticides through food is “probably somewhere between 10,000 and a million times lower than a car accident.” He has also said that he drank glyphosate and would do it again “to demonstrate its harmlessness.” [24]

AgBio Chatter with industry and academics

Internal documents also shed light on how Monsanto and its PR firms worked to coordinate messaging and lobbying efforts with their academic allies using a private email list called AgBioChatter. The list included two Monsanto executives, DuPont’s former director of scientific affairs, two higher-ups at the biotechnology industry trade association, and more than a dozen academics with industry connections — many of them affiliated as experts or ambassadors with the pesticide-industry funded marketing campaign GMO Answers (described in Tactic 5) run by Ketchum. Several of the academics also served in leadership roles for industry front groups connected with pesticide companies, such as Genetic Literacy Project, Academics Review, and Sense About Science (described in Tactic 3). These groups, along with the listserv itself — identified under the name “Academics (AgBioChatter)” — appear among the “industry partners” in Monsanto’s PR plan to defend glyphosate. [25]

Chemical industry executives and industry-friendly academics discussed lobbying and PR strategies on the AgBioChatter list

obtained via FOIA

Emails from the listserv highlight messaging themes: for example, efforts to frame science documenting health concerns about pesticides as “agenda-driven,” while studies that claim safety are “pro science.”[26] Another major theme involved efforts to discredit industry critics.

Records show that former Monsanto Communications Director Jay Byrne peppered the listserv with calls to action and messaging suggestions to confront influencers who raised concerns about GMOs, including the scholar and environmental activist Vandana Shiva, plant scientist and former Purdue Professor Don Huber, and the nonprofit group Consumers Union. As we describe in Tactic 4, attacks on critics have been a key component of Monsanto’s communications efforts to protect glyphosate.

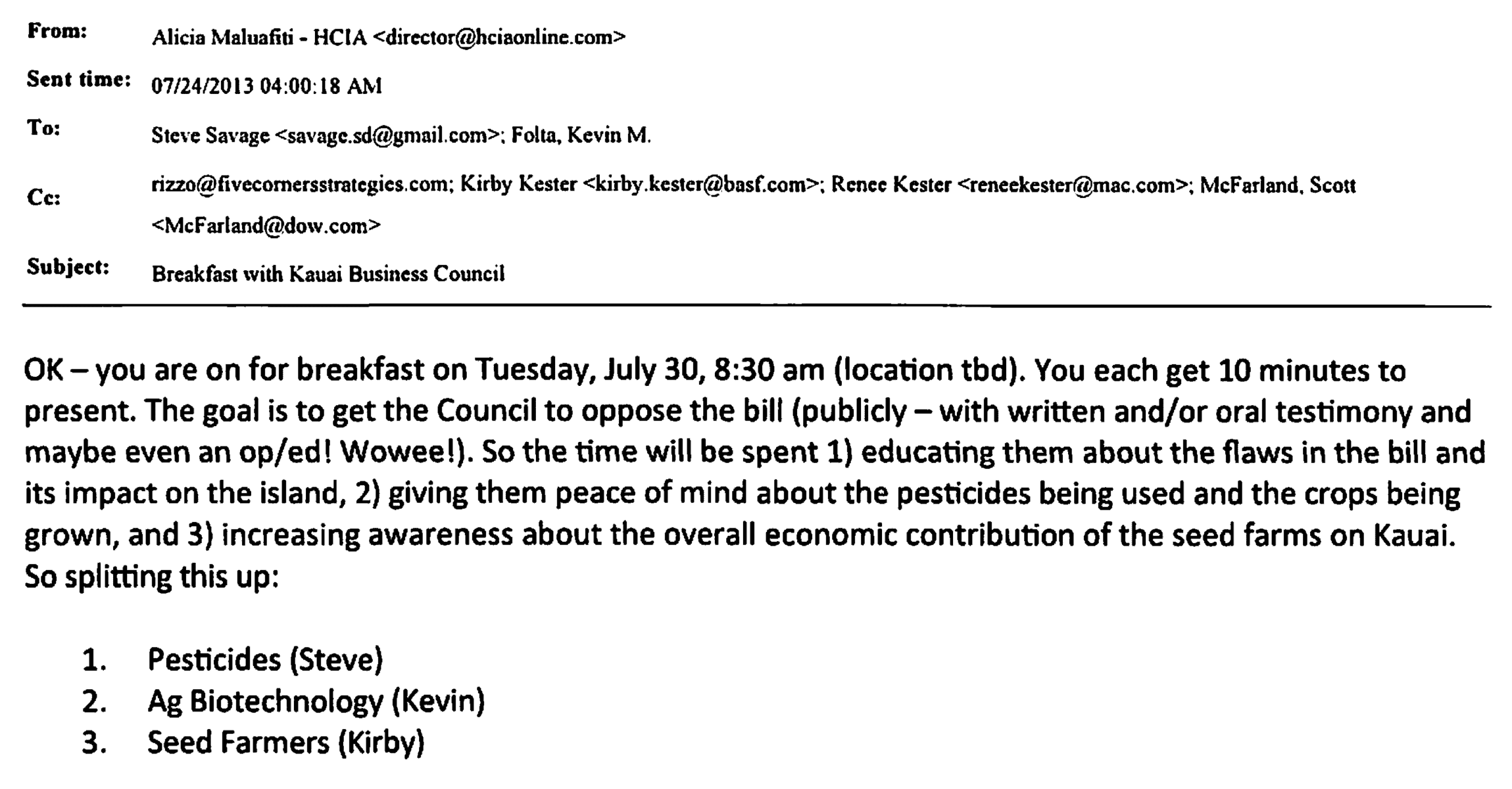

Academics provide lobbying aid

These internal records also show how pesticide companies and affiliated trade associations tap academic networks to help lobby for industry-favorable policy. In one example, the Hawaii-based Hawaii Crop Improvement Association (HCIA) — a trade group funded by Corteva CropSciences (formerly DowDuPont) and Bayer — recruited and paid academics, including Kevin Folta, to travel to the state in 2014 to help lobby against proposed pesticide restrictions there. The industry trade group set up the meetings and coordinated the scientists’ messaging, according to internal emails.[27] One email describes key messages to be presented to the Kauai Business Council, including, “Giving them peace of mind about the pesticides being used and the crops being grown,” including glyphosate.[28] Despite these industry ties, Folta promoted the trip as an effort by “independent expert scientists” who went to Hawaii “simply to share science.”[29]

The lack of public disclosure about pesticide industry ties to academics who lobby for industry interests is a recurring problem. In another example, Bruce Chassy, a professor emeritus of food and nutrition at the University of Illinois, appeared frequently in the media as an independent expert promoting GMOs and lobbying to keep them unlabeled. In May 2016, the Associated Press quoted Chassy twice in a single week as an independent expert on the topic.[30] But he, too, was receiving funds from Monsanto. Two months earlier, Monica Eng of WBEZ revealed that Chassy had received $57,000 from Monsanto over a two-year period to travel, write and promote GMOs, and that Monsanto donated at least $5.1 million to the University of Illinois Foundation between 2005 and 2015.[31]

Internal documents posted by the New York Times further reveal that, for years, Chassy had been lobbying federal regulators to deregulate GMOs while receiving funds from Monsanto.[32] In 2011, when the EPA proposed a data requirement to better understand the health and environmental impacts of genetically engineered crops, Chassy organized a lobbying effort to defeat it.[33] According to Chassy’s notes from a conference call, shared with Monsanto executives and others, the goal was “to ensure the EPA proposal never sees the light of day.”[34] For this lobbying effort, Chassy enlisted other high-profile academics, the internal documents show, including Nina Fedoroff, a molecular biologist at Penn State University, who was at that time president of the American Academy for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), the world’s largest multidisciplinary scientific society.[35]

In July 2011, Chassy emailed Eric Sachs of Monsanto [36] to share that Fedoroff and 60 members of the National Academy of Sciences had sent a letter to EPA [37] opposing the EPA data requirement for genetically engineered foods. “Nina really picked up the ball and moved it down the field,” Chassy wrote. Chassy later reported to Sachs that he and Fedoroff had a “surprisingly productive meeting” with the EPA’s Steve Bradbury that had been arranged by Stanley Abramson, a lobbyist for the biotechnology industry trade group.[38] Interspersed in Chassy’s emails to Sachs were queries about whether Monsanto had sent a check to the University of Illinois Foundation in support of Chassy’s “biotechnology outreach and education activities.”[39]

Industry-funded “boot camps” for journalists, scientists

Professors Chassy and Folta also collaborated with the pesticide industry to arrange a series of messaging training programs at public universities — described as “boot camps” — to shape coverage of pesticides and GMOs in the popular press. “Independent scientists and researchers can play a unique role in reframing the GMO debate because the public holds them in such high esteem,” noted a promotional flier for the Biotech Literacy Project “boot camps.” The three-day conferences held at University of Florida in 2014[40] and University of California, Davis in 2015[41] were “dedicated to helping scientists and journalists work together to bring science to the public in a way that is accessible and persuasive,” according to the agendas. Expenses for the two events ran to over $300,000, and routed through a nonprofit group called Academics Review, co-founded by Chassy.[42] Although the group claimed to be independent of industry, tax records show that Academics Review received most of its funding (including funding for the boot camps) from the Council for Biotechnology Information (CBI) — a trade group funded by chemical giants BASF, Bayer, DowDuPont, and Syngenta.[43]

The agenda left no doubt about the public relations purpose of the boot camps: to provide “broad communications skills training” that participants could use for “reframing the food safety and GMO debate” and lobbying for those products. “Participants will be provided both training and hands-on assistance in developing the tools and support resources necessary to effectively engage the media and appear as experts in legislative and local government hearings,” states the agenda for the UC Davis event. [44] Sessions included “Reframing the Debate: 5 Arguments for GMOs,” “Claiming Your Real-Estate on Social Media,” “Building Trust in Science and the Science of Agriculture,” and “Chasing the Media.”

The pro-pesticide industry bias was not subtle. A panel on organic foods, for example, was moderated by Chassy, who had written a report condemning the organic industry as a marketing scam in 2014.[45] A panel on “GMOs and chemicals” was led by Hank Campbell, president of the industry-funded American Council on Science and Health (ACSH), a group that frequently defends glyphosate and other products made by its funders.[46] Keynote speakers at the UC Davis event included Yvette d’Entremont, who blogs as SciBabe and mounts an ardent defense of pesticides in her writings and public appearances, including talks at farming conferences sponsored by Monsanto and DuPont.[47] In one podcast, for example, d’Entremont claims, “We’ve proven very, very carefully that, once they get into the food supply, [pesticides] are safe for people.”[48] (While SciBabe’s website[49] cites her former job as an analytical chemist, it omits that she worked for Amvac Chemical Corporation, [50] which, according to a Los Angeles Times investigation, did “booming business” selling older dangerous pesticides and fighting to “keep those chemicals on the market as long as possible, hiring scientists and lawyers to do battle with regulatory agencies.”)[51]

SciBabe was also keynote speaker at an industry-funded “boot camp” at UC Davis that coached journalists and academics on how to defend GMOs and pesticides.

Payoff for the pesticide industry’s investment in events like the boot camps can be seen in the post-event press. A few weeks after the UC Davis event, Popular Science ran a flattering “Q&A with SciBabe,” presenting d’Entremont as a credible source on science.[52] The piece was written by Brooke Borel, a journalist who had attended the boot camp. In 2014, a month after attending the University of Florida boot camp, Marc Gunther penned an article in the Guardian claiming that nonprofit organizations like Friends of the Earth and Consumers Union — two groups that have been ardent critics of glyphosate — “can’t be trusted on GMOs.”[53] Gunther, an editor-at-large at the Guardian, noted that he came up with the idea for his article after reading a critique of Consumers Union written by Val Giddings, the former executive of the biotech industry trade group BIO.[54] Gunther did not mention that he had recently moderated a panel about GMO labeling at the industry-funded boot camp, and that Giddings and Bruce Chassy had helped him prepare, according to planning emails.[55] Among the proposed questions Chassy advised Gunther to ask was one about the costs of labeling, referencing a Cornell study that alleged that labeling GMOs would cost a typical family $500 a year.[56] Funded by the same industry trade group — whose members include Monsanto — that funded the boot camps, the study design had been debunked. A Consumers Union rebuttal details the flaws in the study design, finding that the industry-funded study “dramatically overestimates the cost of [GMO labeling].”[57] Another journalist “faculty” member of the 2014 boot camp, Washington Post columnist Tamar Haspel, used her space in the Post a year later to defend glyphosate. The article appeared at a politically important moment, just days before a key Congressional vote on a bill that made it illegal for states to label GMOs. Haspel’s article downplaying cancer concerns of glyphosate quoted David Ropeik, a risk analyst who had shared a panel with her at the boot camp. In her Post opinion column, Haspel did not mention that Ropeik owns a PR firm that serves pesticide industry clients.[58]

[Read more about Haspel’s work here: Our source review of her Washington Post columns about pesticides found multiple examples of undisclosed industry sources and other misleading reporting tactics.]

Gates-funded PR campaign at Cornell

As public universities lent their venues to the boot camps, a longer-term public relations effort was underway — this one under the auspices of an Ivy League institution. By the early 2010s with most commercialized GMOs engineered to tolerate glyphosate use of the chemical was skyrocketing and Monsanto was ramping up its efforts to promote these seeds, and the glyphosate herbicides used to grow them, as safe and necessary to feed the world. Key aid came from the Cornell Alliance for Science, a communications initiative launched in 2014 with an initial $5.6 million grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. [59] (The foundation has since donated a total of at least $22 million to the effort. Additional funders are named on its website, but total revenues are not disclosed).

While the Alliance described its mission to “add a stronger voice for science” and “depolarize the charged debate around GMOs,” African civil society groups have characterized it instead as a “public relations strategy” that spreads “false promises, misrepresentations and alternative facts” in its efforts to convince African countries to accept patented genetically engineered seeds.[60]

_____

“Their immediate goal is to weaken national biosafety laws, thereby removing any barriers to their access to African markets for their contentious high-risk products.”

Statement on Cornell Alliance for Science by the Alliance for Food Sovereignty in Africa

_____

A central strategy of the Alliance has been to recruit and train global fellows in communications, focusing on fellows from regions with pushback on policies favorable to the biotech industry, particularly African countries that have resisted GMO crops. In 2018, for example, twenty-seven Global Leadership Fellows were chosen from seven countries — Nigeria, Uganda, Kenya, Ghana, Zambia, Zimbabwe, and Tanzania — to attend a 12-week training program to learn “strategic planning, grassroots organizing, the science of crop biotechnology and effective communications” to help them advocate for access to biotechnology. [61] More than half the fellows were journalists or marketing professionals.

The Gates Foundation has also donated heavily to efforts in Africa to transition farmers away from traditional seeds and crops to commercial seeds and synthetic fertilizer to grow commodity crops for the global market, promising those efforts would boost agricultural productivity and lift small-scale farmers out of poverty. The foundation has donated over $600 million to its flagship project in the region, the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA), which works in 11 countries to transition farmers to high-input industrial agriculture.[62] , [63] But these efforts have failed to improve food security, according to a 2022 review commissioned by AGRA donors.[64] The program has also been criticized by African food sovereignty groups, [65] faith leaders, [66] and researchers [67] who say AGRA is increasing corporate control in food systems, damaging the environment, and increasing debt for farmers.[68]

Although its main focus is promoting GMO seeds and crops, Alliance fellows have also defended glyphosate-based Roundup products, using similar messaging and tactics that appear in Monsanto’s strategy documents. As one example, the Cornell-based group jumped into the glyphosate debate with a scathing critique of the IARC cancer report, echoing the anti-IARC theme described in Monsanto’s PR plan. [69] In a 2017 blog on the Alliance for Science website, Mark Lynas, a writer for the group, described the highly respected IARC cancer research panel as “a flaky offshoot” of the World Health Organization, and claimed its glyphosate report was a “witch hunt” orchestrated by people overcome with “hysteria and emotion” who committed an “obvious perversion of both science and natural justice” by reporting cancer concerns. Glyphosate, Lynas claimed, is the “most benign chemical in world farming.” [70]

In another example of playing defense for the pesticide industry, the Alliance served a key function in trying to discredit the U.S. Right to Know’s (USRTK) FOIA investigation into the industry’s academic partnerships — echoing Monsanto’s strategy to counter these investigations. As one of its first public efforts, the Alliance launched a petition opposing the USRTK public records investigation, describing the FOIA requests as an “anti-science bullying tactic” that would “stifle academic freedom.”[71] Similar messaging appears in Monsanto’s U.S. Right to Know FOIA communication plan, which notes among its objectives: “position this activist tactic as an attack on scientific integrity and academic freedom.”[72] The Monsanto plan even suggests reaching out to a key ally at the Gates Foundation for help. In a section describing plans to enlist “academic support,” the document suggests: “consider asking Robb [Fraley] to engage [Rob] Horsch” (underline in original). The note refers to Monsanto executive Fraley engaging Horsch, a former Monsanto executive who was at that time leader of the Gates Foundation’s Agricultural Development team.

The Gates-funded Cornell Alliance for Science used Monsanto’s “attack on science” framing to try to discredit a FOIA investigation into the pesticide industry’s ties with academics.

_____

While Cornell Alliance for Science says it does not receive any funds from industry, these examples show how Monsanto’s allies provided aid to the company at key moments in the public debate about glyphosate safety. It is also worth noting that the Alliance’s main funder, the Gates Foundation, has had financial ties to Monsanto. In 2010, the Gates Foundation Trust came under criticism for buying 500,000 shares of Monsanto stock.[73] Although the Trust sold the stock, the financial ties continued, through Gates Foundation Trustee Warren Buffet’s company, Berkshire Hathaway, which is also the largest holding of the Gates Foundation Trust. In 2018, Buffett and Berkshire played a key role in supporting the merger between Bayer and Monsanto. As the financial press reported at the time, Buffet increased Berkshire’s stake in Monsanto stock by 19 million shares (a 62 percent jump) just as Bayer was closing in on the merger — signaling support for the deal to investors at a crucial moment. As Quartz reported, “One of the world’s most controversial mergers just got the biggest cheerleader of all: Warren Buffett.”[74] [75]

The GMO-pesticide connection: a battle in Hawaii

The work of the Cornell Alliance for Science also underscores the important connection between genetically engineered crops and pesticide use. To create an enabling environment for GMOs requires that pesticide companies operate with fewer restrictions; so, along with promoting GMOs, the Alliance has focused its communications firepower on fighting important political battles to stop pesticide regulations, notably in Hawaii. In the last couple of decades, some of the world’s biggest agrichemical companies, including Bayer, have taken over massive agricultural land tracts on the islands for genetically engineered crop field trials and seed development. [76] Drawn by the year-round growing season and lax regulatory environment, these companies have made Hawaii ground zero for open-air testing of “restricted use pesticides,” pesticides that are not available to the general public because of their toxicity concerns.

_____

“I have personally witnessed families and lifelong friendships torn apart.”

Fern Holland, Hawaii Alliance for Progressive Action, describes the impact of the “vicious divide-and-conquer tactics” used by Gates-funded Cornell Alliance for Science

_____

In the face of the widespread pesticide spraying on the islands and health and environmental concerns linked to these pesticides, including glyphosate, community advocates have fought to pass pesticide regulations.[77] As one of these advocates shared in an op-ed in the Cornell Daily Sun, “In 2013, as the efforts to pass these county-level regulations picked up steam, Cornell Alliance for Science associates came to our island to undermine community concerns about pesticides. It was the beginning of a massive public relations disinformation campaign designed to silence community concerns.”[78] By 2016, the Alliance had launched a local chapter, the Hawaii Alliance for Science, to counter the communities organizing for regulation.[79]

The writings of Joan Conrow, the managing editor of Cornell Alliance for Science, [80] give a sense of their tactics: In her blog Kauai Eclectic and other media outlets, Conrow accused local advocacy groups working for pesticide reforms of tax evasion, [81] compared a food safety group to the Ku Klux Klan, [82] and critiqued media reports that raise concerns about pesticides.[83]

Despite these attacks, some pesticide regulations did pass. Hawaii was the first in the nation to approve a ban on the brain-damaging insecticide chlorpyrifos, for example. But the wins were not without a huge toll. In the Daily Sun op-ed, the local organizer described the Alliance’s work in Hawaii as “vicious divide-and-conquer tactics to silence those critical of the pesticides used on biotech crops.” These tactics, she noted, have had “a huge impact” on the close-knit rural communities of the islands. “I have personally witnessed families and lifelong friendships torn apart,” she shared. [84]

The Hawaii community groups were not the only ones to speak out about the Cornell Alliance. Many scientists and advocates have documented similar concerns about inaccurate claims and misleading information promoted by the group and its spokespeople.[85] [86] Nevertheless, the Gates Foundation renewed its funding commitment in the Alliance in 2020, and the Alliance announced it is expanding its scope “to counter conspiracy theories and disinformation campaigns that hinder progress in climate change, synthetic biology, agricultural innovations and other key issues.”[87]

As we demonstrate in this section, prestigious academic institutions — entities often trusted by the public and viewed as independent — provided valuable platforms for Monsanto and other pesticide companies to move their product-defense messaging for glyphosate and the GMO seeds designed to tolerate the chemical. These academic allies are at the core of the industry’s public relations spin. In the next section we take a closer look at the role other impartial- and scientific-sounding groups play in the pesticide industry’s disinformation network, and how Monsanto moved its glyphosate-defense messaging through a wide range of these third-party allies — groups that took their messaging cues from the company and its PR firms.

_________

More information

You can read the full Merchants of Poison report here.

See also the posted excerpt of Tactic 1: Corrupting science

Sign up for the U.S. Right to Know newsletter to follow the latest news on our investigations.

About the author: Stacy Malkan is the co-founder and managing editor of U.S. Right to Know, a non-profit research group whose investigation of pesticide industry disinformation and lobbying informs this report.

Additional collaborators: Kendra Klein, PhD is Deputy Director of Science with Friends of the Earth. Dr. Klein provided support on the state of the science on pesticides and their impacts on ecosystems and public health. Anna Lappé is an author and sustainability advocate who provided editorial, writing, and research support and a strategic advisor to Real Food Media.

Endnotes

[1] Giddings, Val. (2014, October 23). RE: Colorado and Oregon Labeling Campaign. U.S. Right to Know. usrtk.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/scientists-poll-well-.pdf

[2] Ibid.

[3] 21st Annual Edelman Trust Barometer. Online survey in 28 countries. (2021). https://www.edelman.com/sites/g/files/aatuss191/files/2021-03/2021%20Edelman%20Trust%20Barometer.pdf

[4] Schaffer, H. D., & Ray, D. E. (2018, November 30). Questionable changes in how AG Research in land-grant universities is funded. Agricultural Policy Analysis Center. http://www.agpolicy.org/weekcol/2018/952.html

[5] University of Minnesota. (Online). Cargill Building – microbial and Plant Genomics. http://www1.umn.edu/twincities/maps/CargillB/

[6] Food and Water Watch. (2012, March). Public Research, Private Gain: Corporate Influence over University Agricultural Research. https://foodandwaterwatch.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Public-Research-Private-Gain-Report-April-2012.pdf.

See also: Hettinger, J. (2021, November 15). Corporate money keeps university ag schools ‘relevant, ’ and makes them targets of donor criticism. Harvest Public Media. https://www.stltoday.com/news/local/education/corporate-money-keeps-university-ag-schools-relevant-and-makes-them-targets-of-donor-criticism/article_b8afe11a-46e0-567b-97a5-b752c1a1a934.html

[7] Ruskin, G. (2021, June 11). UCSF Chemical Industry Documents Library now hosts USRTK Collection. U.S. Right to Know. usrtk.org/our-investigations/ucsf-industry-documents-library-to-hold-key-agrichemical-industry-papers/

[8] Monsanto Company Confidential Document. (2019, July 25). U.S. Right to Know FOIA Communications Plan. usrtk.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/2019-Monsanto-USRTK-FOIA-Communications-Plan.pdf

[9] Ibid.

[10] New York Times. (2015, September 05). Biotech Industry’s Big Gifts to the University of Florida https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/2303691-kevin-folta-uoffloridadocs.html

[11] Lipton, E. (2015, September 05). Food Industry enlisted academics in G.M.O. lobbying war, emails show. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/09/06/us/food-industry-enlisted-academics-in-gmo-lobbying-war-emails-show.html

[12] Ibid.

[13] New York Times. (2015, September 05). A Florida professor works with the Biotech Industry. [Email]. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2015/09/06/us/document-folta.html

[14] Folta, K. (Online). University of Florida deep Monsanto Ties. [Response to Reddit Thread]. U.S. Right to Know. usrtk.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/No-formal-connection-to-Monsanto.png

[15] Folta, K. (2015, September). Bingo! U.S. Right to Know. usrtk.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Not-my-work.png

[16] Biofortified Board. (2019, January 28). Statement on Kevin Folta and conflicts of interest. Biofortified. https://biofortified.org/2018/08/kevin-folta-coi/

[17] New York Times. (2015, September 05). A Florida professor works with the Biotech Industry. [Email]. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2015/09/06/us/document-folta.html

[18] Belluz, J. (2016, April 05). The truth about WebMD, a hypochondriac’s nightmare and big pharma’s dream. Vox. https://www.vox.com/2016/4/5/11358268/webmd-accuracy-trustworthy

[19] Anderson, Liz; Folta, Kevin; Spurgat, Jennifer; Bayer Crop Science. (2015). [Email]. UCSF Chemical Industry Documents. https://www.industrydocuments.ucsf.edu/docs/xlbm0226

[20] New York Times. (2015, September 05). A Florida professor works with the Biotech Industry. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2015/09/06/us/document-folta.html

[21] Payne, Jack M. (2014, July 21). RE: ASPB Follow-up. [Email]. U.S. Right to Know. usrtk.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/University-of-Florida-stance-on-GMOs.pdf

[22] Florida Trend. (2014, July 17). Jack Payne of UF on GMOs and climate change. https://www.floridatrend.com/article/17361/jack-payne-of-uf-on-gmos-and-climate-change

[23] Payne, Jack M. (2021, July 21). RE: ASPB Follow-up. [Email]. U.S. Right to Know. usrtk.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/University-of-Florida-stance-on-GMOs.pdf

[24] Malkan, Stacy. (2021, October 26). The misleading and deceitful ways of Dr. Kevin Folta. U.S. Right to Know. usrtk.org/our-investigations/kevin-folta/

[25] Monsanto Internal Document. (2015, February 23). Glyphosate: IARC. U.S. Right to Know. usrtk.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/72-Document-Details-Monsantos-Strategy-Regarding-IARC.pdf

[26] Folta, Kevin M. (2015, February 16). RE: Points Against Labeling. [Email]. U.S. Right to Know. usrtk.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/AgBioChatter-Academics-emails.pdf

[27] Maluafili, Alicia. (2013, July 24). Breakfast with Kauai Business Council. [Email]. U.S. Right to Know. usrtk.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Biofortified-boys-messaging.pdf

[28] Ibid.

[29] Digital, G. (2018, January 12). Hawaii science ‘SWAT team’ engages public fears fanned by anti-GMO activists. Genetic Literacy Project. https://geneticliteracyproject.org/2013/07/29/hawaii-science-swat-team-engages-public-fears-fanned-by-anti-gmo-activists/

[30] Kolpack, D. (2016, May 12). Opponents of GMO law find friendly audience in Fargo. Associated Press. https://eu.desmoinesregister.com/story/money/agriculture/2016/05/12/opponents-gmo-law-find-friendly-audience-fargo/84299424/ ; Borenstein, S. (2016, May 17) National Academy of Science report says there’s no evidence that eating genetically modified food will hurt you or harm the environment. Associated Press. https://www.usnews.com/news/science/articles/2016-05-17/report-genetically-altered-food-safe-but-not-curing-hunger

[31] Eng, M. (2016, April 01). Why didn’t an Illinois professor have to disclose GMO funding? WBEZ Chicago. https://www.wbez.org/stories/why-didnt-an-illinois-professor-have-to-disclose-gmo-funding/eb99bdd2-683d-4108-9528-de1375c3e9fb

[32] New York Times (2015, September 05). A University of Illinois professor joins the fight. [Emails]. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2015/09/05/us/document-chassy.html?mtrref=www.google.com&gwh=5DC20C892C493561A0497F4770CE2DDF&gwt=regi&assetType=REGIWALL

[33] Chassy, Bruce. (2011). Re: Need help. [Email]. UCSF Chemical Industry Documents. https://www.industrydocuments.ucsf.edu/chemical/docs/#id=fpvm0226

[34] Chassy, Bruce. (2011, September 12). Re: Response to proposed EPA Rule Making — possible next steps. [Email]. U.S. Right to Know. usrtk.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Chassy-notes-from-Sept.-2011-lobby-call-.pdf

[35] AAAS (2011, March 3). (Online) https://www.aaas.org/news/aaas-president-nina-v-fedoroff-expanding-sciences-role-across-international-borders

[36] Chassy, Bruce. (2011, July 5). RE: EPA letter. [Email]. U.S. Right to Know. usrtk.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Federoff-role-in-EPA-reg-opposition-.pdf

[37] Nina Fedoroff et. al. (2011, July 5). Letter to US EPA. National Academy of Sciences. https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7hhP5QasNtsNzk2YTczODktZmQxMi00ZWE1LTljNWEtYTdjZmUzNGMxNGU1/view?resourcekey=0-ZupO8FT0G0JReuMpzuVwhA

[38] Chassy, Bruce. (2011, October 17). RE: Question. [Email]. U.S. Right to Know. usrtk.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/meeting-with-EPA_Federoff_Chassy.pdf

[39] Chassy, Bruce. (2011, July 5). RE: EPA letter. [Email]. U.S. Right to Know. usrtk.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Federoff-role-in-EPA-reg-opposition-.pdf

[40] BLP 2014 Schedule. (2014). University of Florida, Gainesville. U.S. Right to Know. usrtk.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/TamarHaspel1.pdf

[41] BLPII: 2nd Annual Biotechnology Literacy Project Bootcamp Flyer. (2015). University of California, Davis. U.S. Right to Know. usrtk.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/BLP-Davis-Flyer-2015.pdf

[42] Malkan, S. (2018, May 31). Academics Review: The making of a Monsanto front group (see Academics Review tax records). U.S.Right to Know usrtk.org/gmo/academics-review-the-making-of-a-monsanto-front-group/

[43] Malkan, S. (2017, December 07). Monsanto fingerprints found all over attack on organic food. Huffpost. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/monsanto-fingerprints-fou_b_10757524

[44] BLPII: 2nd Annual Biotechnology Literacy Project Bootcamp Flyer. (2015). University of California, Davis. U.S. Right to Know. usrtk.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/BLP-Davis-Flyer-2015.pdf

[45] Academics Review (2014, April 7). Why consumers pay more for organic foods: Fear sells and marketers know it. https://web.archive.org/web/20140410181250/http://academicsreview.org/2014/04/why-consumers-pay-more-for-organic-foods-fear-sells-and-marketers-know-it/

[46] Kroll, A., & Schulman, J. (2013, October 28). Leaked documents reveal the secret finances of a pro-industry science group. Mother Jones. https://www.motherjones.com/politics/2013/10/american-council-science-health-leaked-documents-fundraising/

[47] Malkan, S. (2020, April 29). Scibabe says eat your pesticides. But who is paying her? U.S. Right to Know. usrtk.org/gmo/sci-babe-yvette-dentremont/

[48] Talking Biotech podcast (2015, Oct. 3). 019 The SciBabe Talks Toxins; Your Questions Answered, https://web.archive.org/web/20201119022952/https://www.talkingbiotechpodcast.com/tag/scibabe/

[49] About SciBabe. (2021, March 16). https://scibabe.com/about-scibabe/

[50] Yvette d’Entremont – Researchgate. (Online). https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Yvette-Dentremont-2

[51] Miller, T. C. (2007, April 08). Pesticide maker sees profit when others see risk. Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2007-apr-08-me-amvac8-story.html

[52] Brooke Borel (2015, June 26). Q&A with SciBabe on GMOs, swearing, and more. Popular Science. https://www.popsci.com/qa-scibabe/

[53] Gunther, M. (2014, July 16). Why NGOs can’t be trusted on GMOs. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/2014/jul/16/ngos-nonprofits-gmos-genetically-modified-foods-biotech

[54] Gunther, M. (2014, July 16). A deeper dive into NGO’s claims on biotech foods. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/2014/jul/16/ngo-claims-biotech-foods-gmos-emails

[55] Folta, Kevin. (2014, May 27). RE: Your presentation at BLP 2014 – GMO Labelling – What Works? [Email]. U.S. Right to Know. usrtk.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Marc-Gunther_Biotech-Literacy-Project.pdf

[56] Ibid.

[57] Hansen, M. (2014, May 29). CU response to Cornell Study on cost of GE labeling. Consumer Reports. https://advocacy.consumerreports.org/research/cu-response-to-cornell-study-on-cost-of-ge-labeling/

[58] Haspel, T. (2015, Oct. 4). It’s the chemical Monsanto depends on. How dangerous is it? Washington Post https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/food/its-the-chemical-monsanto-depends-on-how-dangerous-is-it/2015/10/04/2b8f58ee-67a0-11e5-9ef3-fde182507eac_story.html. See also Ropeik & Associates. (Online). Clients. https://www.dropeik.com/dropeik/clients.html

[59] Shackford , S. (2014, August 21). New Cornell Alliance for Science gets $5.6 million grant. Cornell Chronicle. https://news.cornell.edu/stories/2014/08/new-cornell-alliance-science-gets-56-million-grant

[60] Alliance for Food Sovereignty in Africa. (2020, January 25). Seeds of Neo-Colonialism – Why the GMO Promoters Get It So Wrong About Africa. https://afsafrica.org/seeds-of-neo-colonialism-why-the-gmo-promoters-get-it-so-wrong-about-africa/

[61] Cornell Alliance for Science. Our 2018 Global Fellows (online). https://allianceforscience.cornell.edu/fellows/2018

[62] Focus Countries. AGRA. (Online). https://agra.org/focus-countries/

[63] Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. (2012). Helping poor farmers, changes needed to feed 1 billion hungry. https://www.gatesfoundation.org/ideas/media-center/press-releases/2012/02/helping-poor-farmers-changes-needed-to-feed-1-billion-hungry

[64] Malkan, S. (2022, March 17). Gates Foundation agriculture project in Africa flunks review. U.S. Right to Know. usrtk.org/bill-gates-food-tracker/gates-foundation-agriculture-project-in-africa-flunks-review/

[65] Secretariat. (2021, September 22). Press release: 200 organizations urge donors to scrap Agra. Alliance for Food Sovereignty in Africa. https://afsafrica.org/press-release-200-organisations-urge-donors-to-scrap-agra/

[66] Southern African Faith Communities and Environment Institute (SAFCEI). (2018). Press release: African faith communities tell Gates Foundation, “big farming is no solution for Africa”. https://safcei.org/press-release-african-faith-communities-tell-gates-foundation-big-farming-is-no-solution-for-africa/

[67] Wise, Timothy. (2020) Failing Africa’s Farmers: An Impact Assessment of the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa, Tufts University Global Development and Environment Institute. https://sites.tufts.edu/gdae/files/2020/07/20-01_Wise_FailureToYield.pdf ; and Mkindi, Abdallah et al. (2020). False Promises: The Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA). https://www.rosalux.de/fileadmin/rls_uploads/pdfs/Studien/False_Promises_AGRA_en.pdf.

[68] Malkan, S. (2021, October 15). Critiques of Gates Foundation Agricultural Interventions in Africa. U.S. Right to Know. usrtk.org/our-investigations/critiques-of-gates-foundation/

[69] Monsanto Internal Document. (2015, February 23). Glyphosate: IARC. U.S. Right to Know. usrtk.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/72-Document-Details-Monsantos-Strategy-Regarding-IARC.pdf

[70] Lynas, M. (2020, September 15). Europe still burns witches – if they’re named Monsanto. Alliance for Science. https://allianceforscience.cornell.edu/blog/2017/11/europe-still-burns-witches-if-theyre-named-monsanto/

[71] Alliance for Science. (2015, March 5). Stop the next Climategate: Stand with public sector scientists and show them your support against agenda-driven bullying. https://web.archive.org/web/20150305065123/http://cas.nonprofitsoapbox.com/science14

[72] Monsanto Internal Document. (2019, July 25). U.S. Right to Know FOIA Communications Plan. U.S. Right to Know. usrtk.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/2019-Monsanto-USRTK-FOIA-Communications-Plan.pdf

[73] Vidal, J. (2010, September 29). Why is the Gates Foundation investing in GM giant Monsanto? The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/poverty-matters/2010/sep/29/gates-foundation-gm-monsanto

[74] Brennan, V. (2018, May 21). Buffett’s Berkshire increases Monsanto stake as Bayer acquisition nears completion. St. Louis Business Journal. https://www.bizjournals.com/stlouis/news/2018/05/21/buffetts-berkshire-increases-monsanto-stake-as.html

[75] Purdy, C. (2017, February 15). One of the food world’s most controversial mergers just got a hell of a cheerleader: Warren Buffett. Quartz. https://qz.com/911501/warren-buffett-buys-shares-in-monsanto-mon-lending-his-backing-to-the-controversial-merger-with-bayer-bayn/

[76] Bayer AG. (Online). Bayer in Hawaii. https://www.bayer.com/en/us/bayer-in-hawaii

[77] Pala, C. (2015, August 23). Pesticides in Paradise: Hawaii’s spike in birth defects puts focus on GM crops. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2015/aug/23/hawaii-birth-defects-pesticides-gmo

[78] Holland, F. A. (2019, November 21). Guest room: Students should continue to question the ethics of the Cornell Alliance for Science. The Cornell Daily Sun. https://cornellsun.com/2019/11/19/guest-room-students-should-continue-to-question-the-ethics-of-the-cornell-alliance-for-science/

[79] Conrow, J. (2020, September 15). Hawaii joins Alliance for Science Global Network. Alliance for Science. https://allianceforscience.cornell.edu/blog/2016/12/hawaii-joins-alliance-for-science-global-network/

[80] Alliance for Science. (2021, October 11). Joan Conrow. https://allianceforscience.cornell.edu/team/joan-conrow/

[81] Conrow, J. (2015, November 5). Undue outside influence. Journalist Joan Conrow Original Reportage Prose. https://web.archive.org/web/20160826125226/http://www.journalistjoanconrow.com/undue-outside-influence/

[82] Conrow, J. (1970, January 1). Musings: Cowed by anti-science bullies. Kauai Eclectic. http://kauaieclectic.blogspot.com/2017/04/musings-cowed-by-anti-science-bullies.html

[83] Conrow, J. (1970, January 1). Musings: Christopher Pala’s hit piece. Kauai Eclectic. http://kauaieclectic.blogspot.com/2015/08/musings-christopher-palas-hit-piece.html

[84] Holland, F. A. (2019, November 21). Guest room: Students should continue to question the ethics of the Cornell Alliance for Science. The Cornell Daily Sun. https://cornellsun.com/2019/11/19/guest-room-students-should-continue-to-question-the-ethics-of-the-cornell-alliance-for-science/

[85] Malkan, S. (2021, October 28). Cornell Alliance for Science is a PR campaign for the agrichemical industry. U.S. Right to Know. usrtk.org/our-investigations/cornell-alliance-for-science-is-campaign-for-agrichemical-industry/

[86] Malkan, S. (2021, June 11). Mark Lynas promotes the chemical industry’s commercial agenda. U.S. Right to Know. usrtk.org/our-investigations/mark-lynas/

[87] Malkan, S. (2021, March 26). Gates Foundation doubles down on misinformation campaign at Cornell as African leaders call for Agroecology. U.S. Right to Know. usrtk.org/our-investigations/gates-foundation-cornell-misinformation-campaign-african-leaders-call-for-agroecology/