An American virologist asked Wuhan Institute of Virology scientists to edit a briefing he prepared for Congressional staff, according to documents obtained by U.S. Right to Know.

“I certainly do not want to compromise you or your research activities,” wrote leading biosafety expert and virologist James Le Duc to Shi Zhengli, a top virologist at the Wuhan Institute of Virology nicknamed the “Bat Woman,” in April 2020.

“Make any changes that you would like,” he wrote, attaching a copy of his prepared comments.

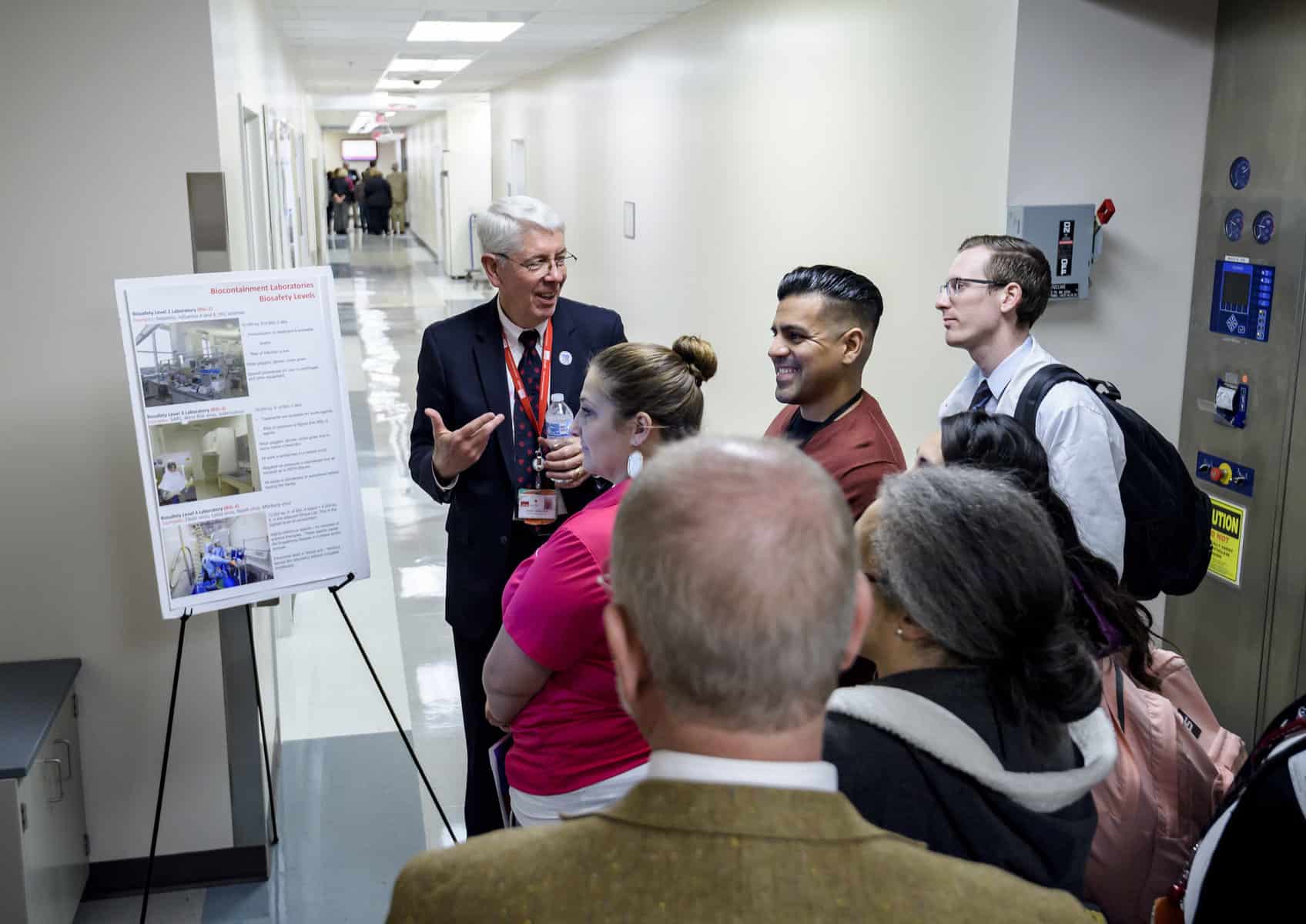

Le Duc also shared his informal testimony with Yuan Zhiming, director of the Wuhan Institute of Virology’s highest security laboratory, the Wuhan National Biosafety Laboratory. Le Duc was the longtime director of the Galveston National Laboratory, another high security or “BSL-4” lab studying coronaviruses. The Wuhan National Biosafety Laboratory and the Galveston National Laboratory have a formal cooperative agreement.

Scientists are continuing to investigate whether SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, may have emerged from a lab accident or spilled over naturally from an animal.

The House Foreign Affairs Committee had asked Le Duc for his input in the pandemic’s early months – and for good reason. The University of Texas Medical Branch’s BSL-4 lab has worked closely with labs in Wuhan for decades, including on issues of laboratory safety.

“Given the long history of collaborations between the GNL and the WIV, I have been approached repeatedly for details on our work,” Le Duc said to his colleagues at the WIV. “Attached is a draft summary that I will be providing to leadership of our University of Texas system and likely to Congressional committees that are being formed now.”

The exchange raises questions about whether Le Duc allowed the Wuhan Institute of Virology’s leading scientists to influence Congress’ understanding of an intensifying pandemic, irrespective of whether they were free to tell the truth.

Days earlier, Le Duc had forwarded Shi information about an article describing calls from Senate Republicans for an investigation of her lab. He asked to speak with her about it, but Shi declined.

But Shi did send back a reply to Le Duc with reference materials – including several articles she co-authored underscoring the possibility of a spillover of bat coronaviruses into humans, including articles describing the creation of engineered viruses with new spike proteins.

“I’ve added some detailed information for your reference,” she wrote.

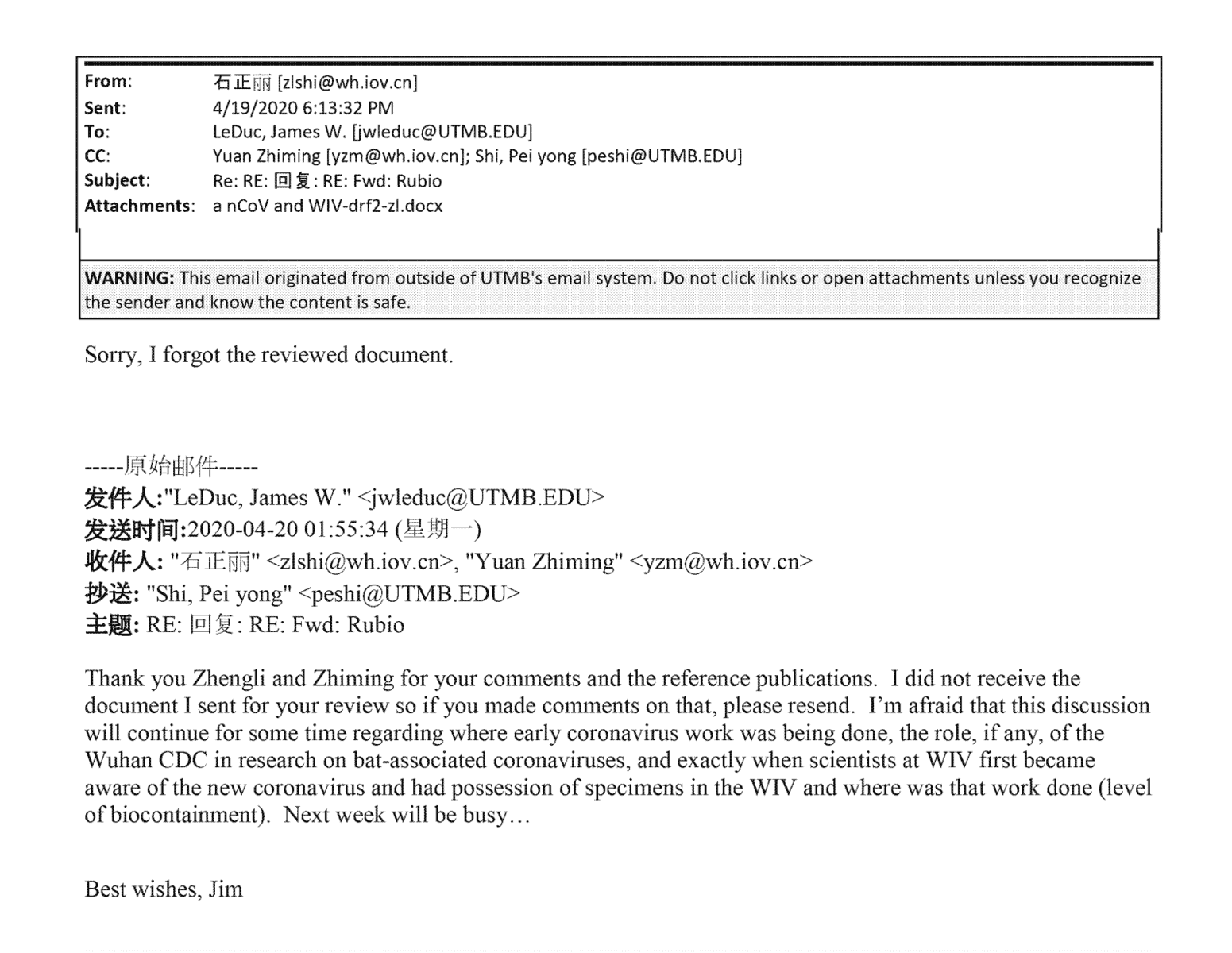

She did not initially send back a copy of Le Duc’s briefing document.

“I did not receive the document I sent for your review so if you made comments on that, please send,” he responded.

“Sorry, I forgot the reviewed document,” Shi wrote back, suggesting that she did indeed make comments or changes.

The name of the file that Shi sent back to Le Duc was “WIV-drf2-zl.docx.” “WIV” may be shorthand for the Wuhan Institute of Virology, while “zl” may refer to Zhengli.

“I’m afraid that this discussion will continue for some time regarding … exactly when scientists at WIV first became aware of the new coronavirus and had possession of specimens in the WIV and where was that work done (level of biocontainment),” Le Duc told Shi.

Indeed, when exactly Chinese authorities became aware of SARS-CoV-2 was a key factor in an inconclusive 90-day review into COVID-19’s origins by the U.S. intelligence community compiled a year later.

“Next week will be busy,” Le Duc wrote on April 19, a Sunday.

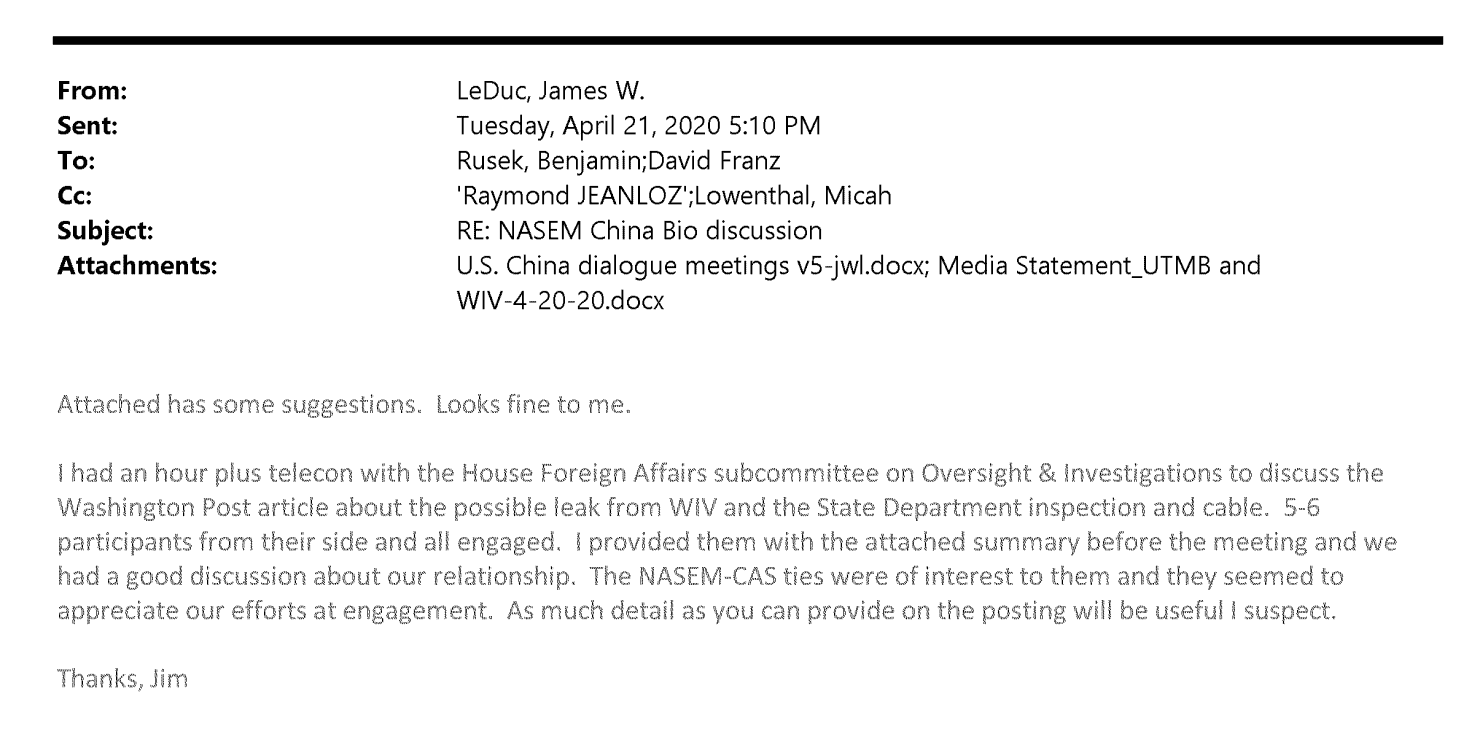

Two days later, on April 21, a Tuesday, Le Duc told colleagues with the National Academy of Sciences that he had met via teleconference with five or six people with the House Foreign Affairs Committee’s Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations.

He passed along information he had shared with committee staff. One of the files attached was saved as “WIV-4-20-20.docx.”

Le Duc had also briefed the full committee’s Republican staff earlier that month, according to notes reviewed by a committee staffer.

The exchange raises questions about how Shi’s influence may have shaped U.S. lawmakers’ understanding of the pandemic’s origins.

It also indicates that at the height of a once-in-a-century public health crisis, the sort of coronavirus pandemic that Shi had been warning about for years, she was concerned about U.S. perceptions of her work.

Le Duc referred questions to UTMB Director of Media Relations Christopher A. Smith.

“Your organization’s characterization of Dr. Le Duc’s intent in contacting Dr. Shi is incorrect,” said Smith. “This email was very early in the outbreak and the information Dr. Le Duc wanted Dr. Shi to review was a description of her research on coronaviruses as he understood it. He asked her to review that description to ensure accuracy should he be asked.”

“Nothing ever came from this exchange, either in the form of a review/comments by Dr. Shi or any specific request for comments regarding her research,” he continued.

But the documents show that Le Duc told Shi that she could make any changes she would like to his briefing.

Smith also said that Le Duc did not testify to Congress. After days of follow-up questions, Smith confirmed that Le Duc had briefed Congressional staff.

A request to see the documents exchanged between Shi and Le Duc was declined.

Shi’s behind-the-scenes influence

In spring 2020, U.S. foreign policy officials privately circulated concerns that Shi’s international influence in the field of virology could cloud an impartial investigation into the possibility of a lab accident at the Wuhan Institute of Virology.

In a State Department memo obtained by U.S. Right to Know, government officials expressed concerns that international virologists would back up Shi before a complete inquiry into the lab in Wuhan was conducted.

“Suspicion lingers that Shi holds an important and powerful position in the field in China and has extensive cooperation with many [international] virologists who might be doing her a favor,” it reads.

In a media interview in April 2020, Le Duc said that Shi was being unfairly scrutinized.

“I just hate to see a world-class coronavirologist, who’s dedicated her life working with this, being scrutinized as the possible source,” he said.

Shi shaped the discourse about the possibility of an escape from her lab in other ways, too.

She also edited a Feb. 2020 commentary that declared there was “no credible evidence” behind claims that SARS-CoV-2 may have been genetically engineered, according to documents obtained by U.S. Right to Know last year.

The commentary’s authors shared a copy with Shi before its publication in Emerging Microbes & Infections, the emails show.

Her involvement was not disclosed.

U.S. Right to Know obtained the records for this article through a Texas Public Information Act request to the University of Texas Medical Branch and from a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit against the State Department.

Written by Emily Kopp