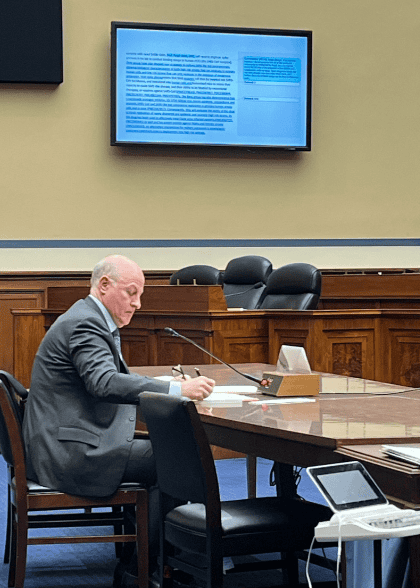

EcoHealth Alliance President Peter Daszak testified before the House Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Pandemic Wednesday about his coronavirus research collaboration situated at the epicenter of the worst pandemic in a century.

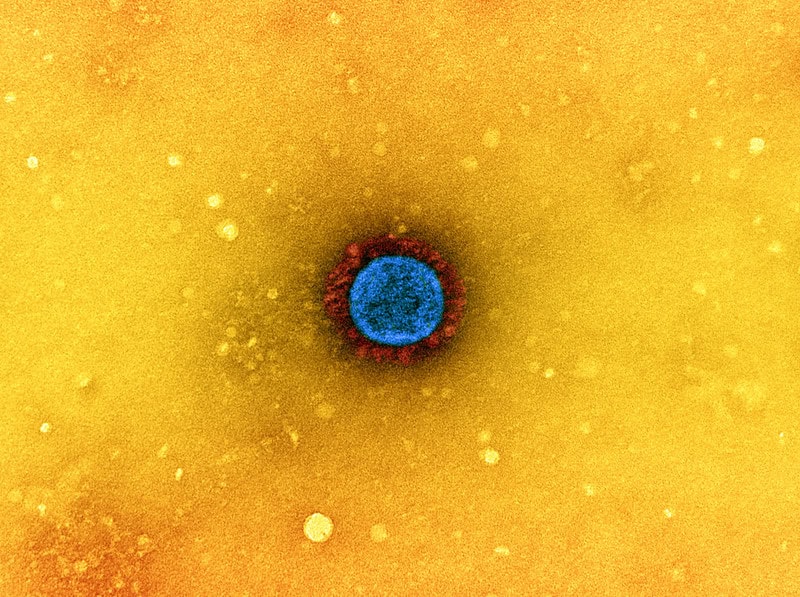

Daszak’s organization collaborated closely with the Wuhan Institute of Virology, a lab complex specializing in bat-borne viruses, including SARS-related coronaviruses. The lab hosted one of the world’s largest coronavirus databases before the data was made inaccessible in the fall of 2019.

Daszak is the first scientist connected to the coronavirus research in Wuhan called to testify before the committee. Democrats and Republicans alike aggressively questioned Daszak on his downplaying of the risks involved in these coronavirus research projects and questioned whether he breached laws regulating federal grantees.

Daszak’s scientific publications, research proposals and grant reports have stoked concerns that the COVID-19 pandemic emerged from his partnering lab in Wuhan. Their collaboration discovered one of the closest known viruses to SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. Their work included gain-of-function experiments that made coronaviruses more deadly. Other internal records obtained by U.S. Right to Know revealed their collaboration’s particular interest in viruses with unique features found in the genome of SARS-CoV-2.

The revelations have provoked questions about whether an organization that promised to safeguard national security by preventing pandemics could have contributed to one.

“EcoHealth’s actions themselves are a threat to national security,” Chair Brad Wenstrup, R-Ohio, said. “Dr. Daszak has displayed a disregard for the risks of gain-of-function research.”

Daszak described the scrutiny of his work as an attack on science and expressed concerns about threats to his safety.

“For years, we repeatedly briefed the U.S. government, international agencies and spoke to the press and public about the risk of a coronavirus outbreak emerging in China from bats,” Daszak said. “Unfortunately in 2019, just as we predicted, a bat origin SARS-related coronavirus emerged and spread in the city of Wuhan, leading to the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Internal records U.S. Right to Know reported earlier this year suggested Daszak intended to outsource risky experiments on viruses like SARS-CoV-2 to Wuhan at an inadequate biosafety level with few protections against airborne viruses — BSL-2. The records suggest this was done in order to save on costs without the knowledge of federal funders. In a draft of a proposal later rejected by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, Daszak said he intended to downplay the extent of the Wuhan lab’s involvement in the project as a whole, the records also showed.

When Daszak sat for a transcribed interview with the committee last year, he testified under oath that the work was slated for BSL-3 in the U.S.

“My understanding for that work it was going to be done at [the University of North Carolina],” Daszak said at the time.

In a new interim report, the committee recommends that the Justice Department investigate Daszak for possible criminal violations, including for making false statements.

Daszak insisted that the final proposal, which states the research would occur in BSL-3, was accurate, in spite of his private note that he would intentionally downplay the extent of the involvement of the Wuhan lab, which typically operated in BSL-2.

Daszak said that conversations with DARPA before the proposal’s submission included an honest discussion about the extent to which the Wuhan Institute of Virology would be involved. He flatly answered “no” when asked whether he had any knowledge of the Wuhan Institute of Virology conducting experiments of concern to generate viruses like SARS-CoV-2.

“There was no attempt to deceive at all,” Daszak said.

These comments did not adequately clarify the discrepancy between his organization’s internal records and his transcribed interview, the committee said.

“The Select Subcommittee will take further steps to address Dr. Daszak’s contempt for the American people,” the committee said in a statement, which did not provide further details.

Daszak has since the pandemic’s earliest days asserted that any suggestion an accident at his partnering lab could have sparked the pandemic is nothing more than conspiracy theory.

But when pressed Daszak acknowledged he did not have perfect insight into all of the samples stored there, the viruses sequenced there or whether the lab moved forward with high-risk research proposals, instead simply insisting that his colleagues in Wuhan are “good scientists.”

“I’ve had a long relationship with the scientists in that lab,” Daszak said. “You get to understand people and you get to know them and you hear the same stories over twenty years, you hear if there are any discrepancies in those stories. … I have no reason to think they were under pressure to lie. … These are good scientists.”

For the first time, the committee broke through prior partisan intransigence — with Democrats focused on a Wuhan wet market while Republicans homed in on the lab. On Wednesday Democrats and Republicans alike grilled Daszak.

The bipartisan questioning broke from years of efforts to stigmatize criticism of EcoHealth as conspiratorial or political — efforts driven in part by Daszak. For years, much of the scrutiny and reporting about Daszak has come from online sleuths and independent reporters.

Rep. Debbie Dingell, D-Mich., asked Daszak pointed questions while defending former National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) Director Anthony Fauci, NIAID, and former NIH Director Francis Collins from criticisms arising from “the bad actions of a single grantee.”

NIAID, an institute under NIH, funded EcoHealth and a subcontract with the Wuhan Institute of Virology.

“We won’t accuse you of creating COVID-19 simply because that’s not what we can do with the available evidence. It doesn’t demonstrate it,” Dingell said. “But to the extent you have considered misrepresenting facts or done so, we will consider that a very serious mistake.”

The hearing did not show whether the COVID-19 pandemic emerged from a lab accident or from nature. Instead, it underscored how much information is still missing about research underway in Wuhan immediately before the first cases emerged.

After years of denials, Daszak acknowledged for the first time that the Wuhan Institute of Virology could have unpublished coronavirus sequences collected over several years immediately before the COVID-19 pandemic, raising the possibility that SARS-CoV-2 was among them.

“It’s possible that they have hidden some viruses that we don’t know about, yes, of course,” Daszak said.

Daszak pitched his work as essential for maintaining open channels of communication with scientists in countries where dangerous viruses circulate. But Daszak only communicated with Wuhan Institute of Virology Senior Scientist Zhengli Shi seeking lab notebooks once after the pandemic started, a committee investigator said. Daszak did little more than forward a letter from the National Institutes of Health, according to the committee. He never asked if the Wuhan lab moved ahead with a research proposal to generate viruses like SARS-CoV-2.

After the hearing, U.S. Right to Know asked Daszak why he hadn’t asked his longtime colleagues in Wuhan for the sequences of viruses sampled by the lab in the years immediately preceding the pandemic. Daszak did not reply.

In addition, the committee noted that it was nearly two years after the deadline – after the pandemic had already begun – that EcoHealth submitted the progress report that should have detailed the research undertaken in the year before the COVID-19 pandemic emerged. While Daszak has faulted technical failings of the NIH website, the committee’s investigation and an NIH forensic electronic audit found his claim to be unsupported.

In addition to the committee’s report, Vanity Fair reported an email obtained by the committee showing a dispute over lab safety between Daszak and University of North Carolina coronavirologist Ralph Baric — another close collaborator of his and of the Wuhan Institute of Virology— after Baric cosigned a letter calling for more serious consideration of the lab origin hypothesis. Baric expressed concern about the experiments being undertaken there at a low biosafety level, BSL-2.

“We checked with Zhengli, who let us know that she used BSL-2 with negative pressure and appropriate PPE,’” Daszak wrote.

“Negative pressure” refers to an air flow system that helps protect lab scientists from aerosols. BSL-2 labs do not typically have negative airflow.

“Your being told a bunch of BS. Bsl2 w negative pressure, give me a break,” Baric wrote back. “You believe this was appropriate containment if you want but don’t expect me to believe it. Moreover, don’t insult my intelligence by trying to feed me this load of BS.”

Daszak repeatedly pitched his work as essential for preventing the next pandemic. But in defending his pre-pandemic work, he defended practices that many scientists criticize as generating new pandemic risks.

Daszak defended conducting bat coronavirus research at a biosafety level with few protections against airborne viruses and not subjecting gain-of-function research on bat viruses to more rigorous administrative oversight, even when those viruses can infect human cells.

Both Republicans and Democrats questioned whether Daszak has been a responsible steward of taxpayer funds. The committee is recommending Daszak and EcoHealth be debarred from receiving further federal funding.

The NIH would have to recommend debarment to the Department of Health and Human Services. They would be ineligible for new federal funding for three years.

The hearing sets the stage for testimony from Fauci in a hearing on June 3. He will testify for the first time since stepping away from NIAID.

The day before the hearing, Senior Advisor to the Director at National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases David Morens, a longtime aide of Fauci and a friend and mentor to Daszak, turned over 30,000 emails to the committee.

“This investigation does not end today,” Wenstrup said.

Wuhan research

EcoHealth’s grant proposals demonstrate an interest in the years immediately before the pandemic to generate viruses that share the unique features of SARS-CoV-2. A virus expedition and engineering proposal named “DEFUSE” — first reported by the independent research group DRASTIC in 2021 — lays out what some scientists have likened to a blueprint for generating a virus like SARS-CoV-2.

Daszak dismissed DEFUSE as “utterly irrelevant to the origins of COVID,” emphasizing that DEFUSE was rejected by the intended funding agency, DARPA.

But pressed by the committee, Daszak conceded he never asked if his collaborators in Wuhan moved ahead with the work independently.

DEFUSE shows the collaboration’s interest in a feature called a furin cleavage site, specifically furin cleavage sites in a position on coronavirus spike protein called the S1/S2 junction. SARS-CoV-2 is unique among viruses in its family for its furin cleavage site at the S1/S2 junction. Asked whether experiments with furin cleavage sites were performed, either in Wuhan or UNC, Daszak answered “no.”

However, some ambiguity remains about the nature of EcoHealth’s work in the months before the pandemic’s start.

EcoHealth submitted its report detailing research and experiments funded by an NIH grant from June 2018 through May 2019 — due in September 2019 — nearly two years later, after the pandemic had already begun.

Wenstrup said in a media interview that some of the work outlined in DEFUSE may have been completed with NIH funding, but the committee has not provided evidence.

“Here was a person that was through these internal emails telling us he was willing to deceive the federal government. But then he goes over to NIH once he’s been turned down there [at DARPA] and he does get the grant,” Wenstrup said.

Daszak said he would provide more records attesting to EcoHealth’s attempts to submit the NIH grant report.

In addition, Daszak made shifting statements throughout the hearing about his access to and knowledge of sequence data stored at the Wuhan Institute of Virology.

In an email released by EcoHealth ahead of the hearing, Daszak said that 15,000 coronavirus samples and around 700 coronavirus genetic sequences discovered with U.S. funding remained at the Wuhan Institute of Virology.

EcoHealth’s NIAID grant was suspended in 2020 after concerns about a lab leak first arose, but reinstated in part so that Daszak could access samples at the Wuhan Institute of Virology, according to two NIAID aides.

Director of the NIAID Division of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases Emily Erbelding told the committee in a transcribed interview that she believed Daszak said he had access to viral samples as he sought reinstatement of his NIAID grant.

Daszak disputed that, attributing it to a conflation of the words “sequences” and “samples,” and stated that a condition of the reinstatement of the grant was that EcoHealth would no longer do on the ground work in China.

Daszak testified that Chinese authorities denied EcoHealth’s request to remove these samples.

In a statement, EcoHealth claimed that the sequences of the Wuhan viruses described in Daszak’s email had all been made public in a 2020 paper, Latinne et al.

But after being pressed by the Subcommittee Staff Director Mitch Benzine, Daszak conceded the paper’s methodology only included virus sampling expeditions up to the year 2015 and that the lab had likely done more sampling since then.

In other words, Daszak had no insight into the sequences of viruses collected by the Wuhan lab in the four years before the pandemic’s outbreak in 2019, or whether SARS-CoV-2 could have been among them.

Research by online sleuths with DRASTIC also suggests the Wuhan lab has discovered viruses that are not published. Coronavirus sequences submitted by the Wuhan lab to public sources dramatically declined after 2015. Yet grant proposals outlined plans to discover more. Daszak said in 2019 that they had discovered 50 SARS-related novel coronaviruses.

Systemic issues

The hearing exposed apparent weaknesses in American biosecurity and biosafety.

Daszak — who the committee alleges has not fully cooperated with their investigation and made false statements under oath — advised the Defense Intelligence Agency, Central Intelligence Agency and the Federal Bureau of Investigation on the origins of COVID-19.

Daszak testified that he spoke with U.S. intelligence agencies about the Wuhan lab and emerging pandemic threats before the COVID-19 pandemic, including the Federal Bureau of Investigation as part of a standing committee at the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

Daszak denied knowledge of ties between the Wuhan lab and the Chinese military, despite them being confirmed in a 2021 State Department fact sheet memo and 2023 declassified U.S. intelligence summary.

When asked about his decision to partner with a lab identified as having a shortage of biosafety training by the State Department, as well as military ties, Daszak testified that the State Department reviews his proposals to NIH.

“Something doesn’t add up. I completely agree because it’s the same State Department that reviews our proposals to NIH and allows us to work with that lab,” Daszak said. “If the State Department considers that to be a military lab, surely they would have said no the WIV is not appropriate for doing this research. However, they reviewed it and said yes. … Something doesn’t add up there because it is them that gave us the go ahead to work with WIV.”

The hearing also showed that risky gain-of-function on animal viruses poised for human infection fall into a regulatory loophole.

Daszak denied that his organization conducted gain-of-function research because the bat coronaviruses had not been shown to infect humans, even though they had been shown to infect human cells in the lab.

But if the government were to accept Daszak’s explanation that his work was not gain-of-function because the animal viruses haven’t spilled over yet — given the premise of EcoHealth’s work is to discover viruses poised to spillover before they do — much of the group’s work would be excluded from more rigorous oversight.

The committee made a number of suggestions in its interim report aimed at strengthening biosafety, including moving screening of high-risk virology out of NIAID, incorporating national security concerns into evaluations of high-risk virology in certain countries, and having a unified regulatory scheme for gain-of-function research across government agencies.

Meanwhile, Daszak confirmed that EcoHealth is preparing a field biosafety manual.