A former U.S. Agency for International Development official founded and worked for a controversial organization benefiting from USAID funds while he continued to receive six-figure paychecks from his USAID job, potentially running afoul of ethics laws, according to documents obtained by U.S. Right to Know.

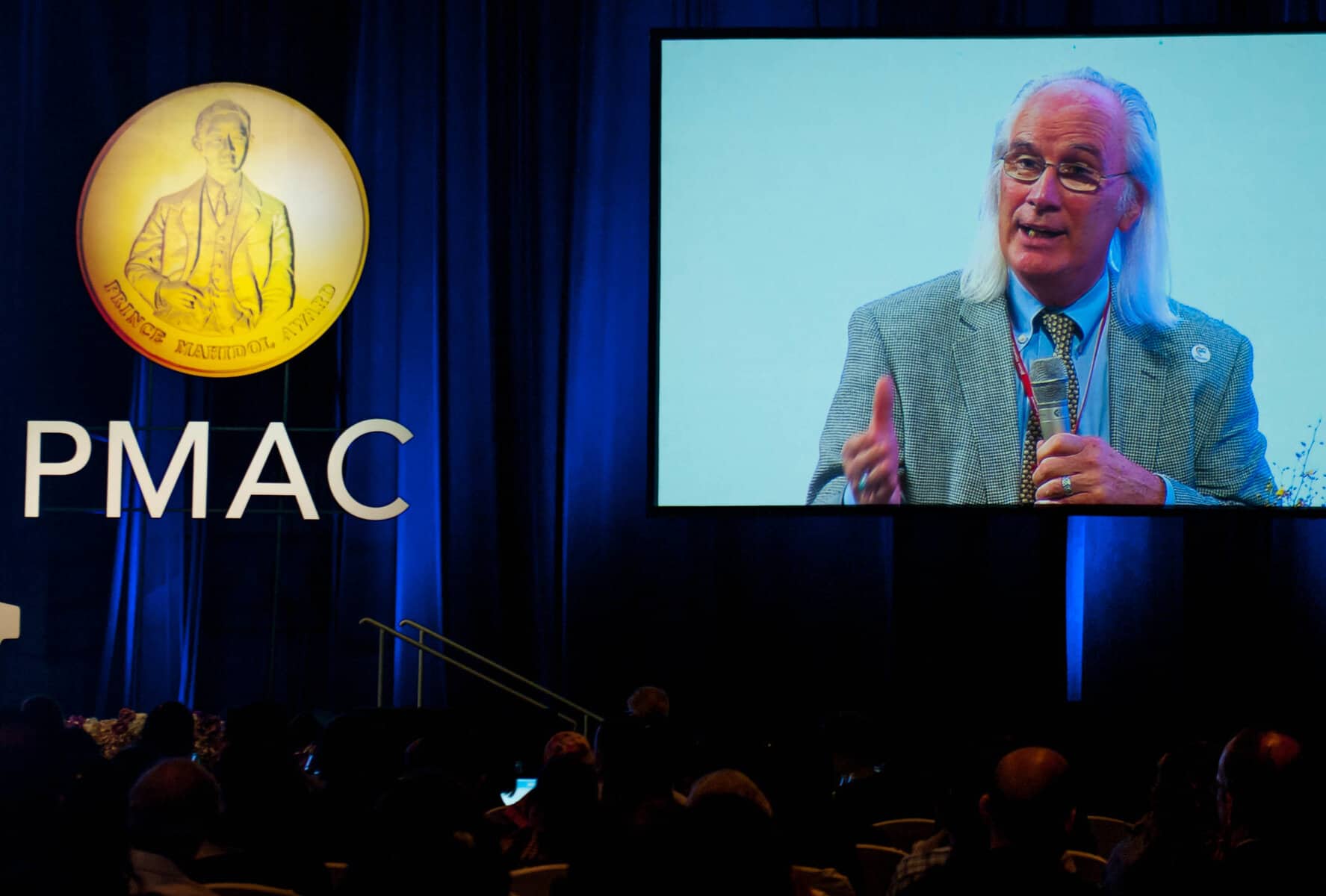

Emerging Pandemic Threats Division Director Dennis Carroll went on to lead the organization — an ambitious, expensive, and potentially dangerous endeavor called the Global Virome Project. Carroll is now the group’s chair.

USAID — a federal agency that typically provides foreign aid — funded a $210 million government program that Carroll designed and oversaw for 10 years called “PREDICT” that served as the “proof of concept” for the Global Virome Project.

Now the Global Virome Project is seeking at least $1.2 billion to collect more than 1 million viruses in wildlife, with the stated aim of forecasting where animals carry pathogens that could evolve to infect humans too. Carroll has pitched the Global Virome Project as the “beginning of the end of the pandemic era.”

Not all experts are convinced Carroll can make good on those promises. Others worry the fieldwork may pose its own pandemic risks.

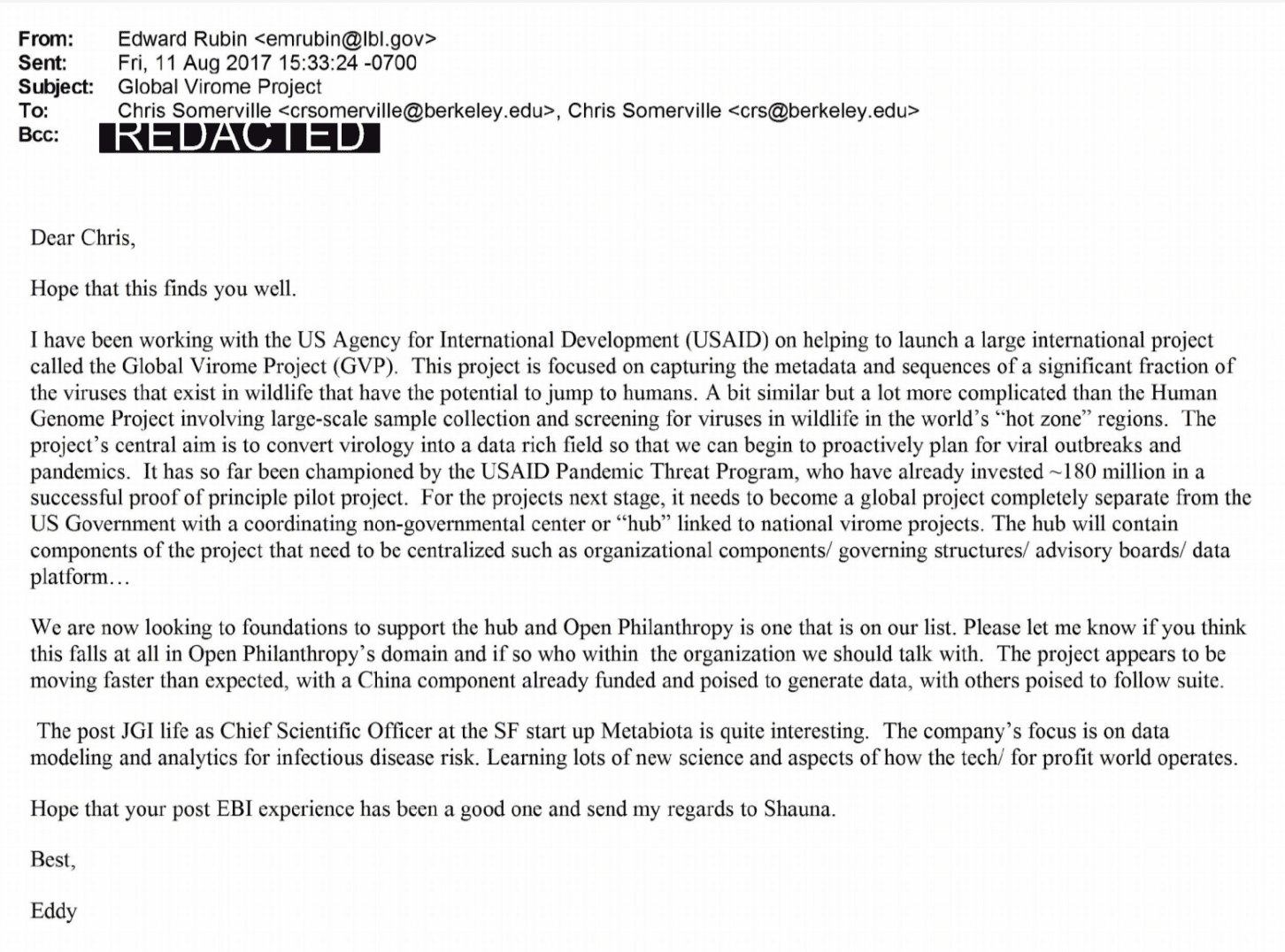

Although the Global Virome Project is controversial even within the field of virology, the idea gained credibility with Carroll’s help and his use of the imprimatur of USAID, the emails suggest.

They indicate that Carroll’s work as USAID’s leader in viral surveillance and as the chair of the Global Virome Project overlapped for years.

Carroll organized calls and meetings on the project’s work with other co-founders, sought donations and helped refine fundraising pitches, pushed favorable messages in the press, and consulted on its application for tax-exempt status with the Internal Revenue Service — all while still working for USAID.

In a December 2018 email from his USAID email address, for example, Carroll proposed a list of board members of the Global Virome Project, including himself, and looped in other project cofounders.U.S. Right to Know obtained the emails through the Freedom of Information Act and the California Public Records Act in an investigation of potentially dangerous viral research funded through taxpayer dollars.

A Global Virome Project board member said that the idea was “championed by the USAID Emerging Pandemic Threats Division” in one August 2017 pitch.

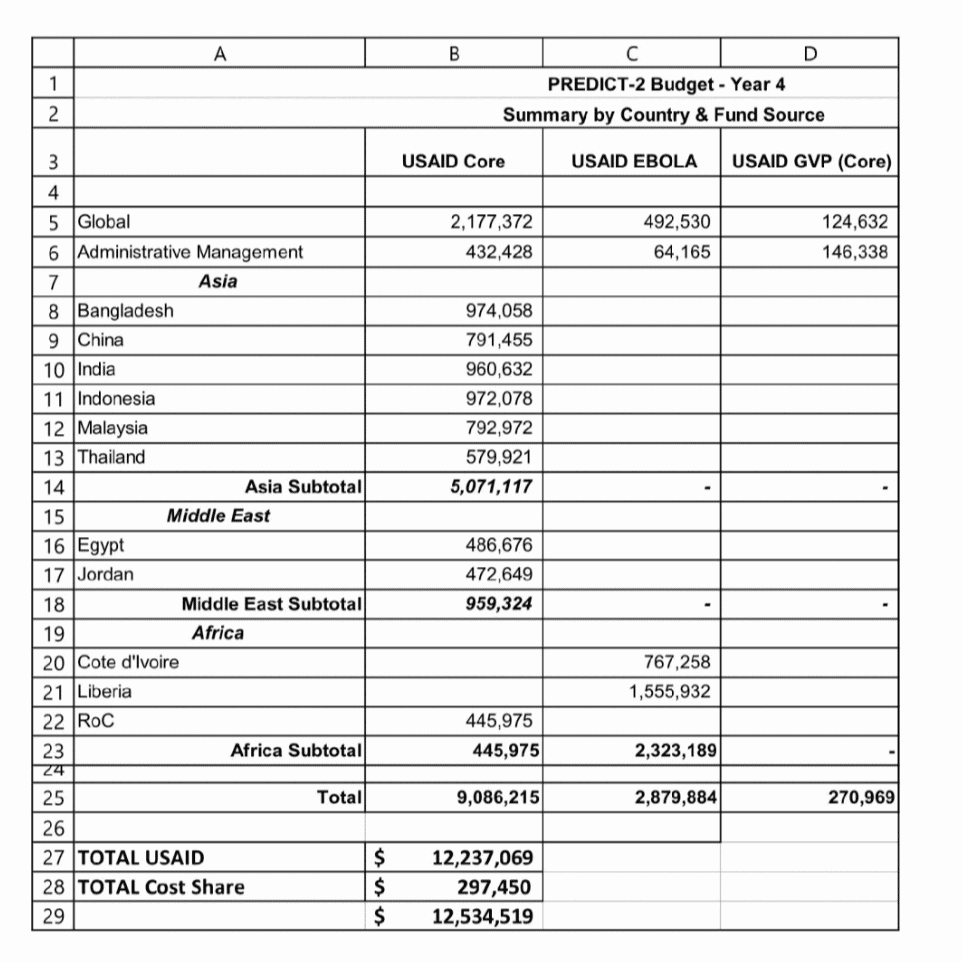

Under Carroll’s helm, USAID’s Emerging Pandemic Threats Division spent at least $270,969 in funds related to “GVP,” the emails show.

“That’s troubling,” said Walter Shaub, former director of the Office of Government Ethics, an ethics agency for executive branch employees.”Separately, his use of a USAID email address is troubling if GVP is not a government project.”

As Global Virome Project supporters made their pitch in Bangkok and Beijing, emails show USAID partially paid for the trips.

Carroll told the media he founded the Global Virome Project after he left his job at USAID.

But the emails show he started in-depth work on the Global Virome Project as early as March 2017, and received six-figure USAID paychecks in 2017, 2018 and 2019. For example, in 2019, USAID paid Carroll $166,500, the maximum allowed for a rank-and-file federal employee.

“The law is clear that officials cannot use government resources to benefit themselves or prospective employers,” said Kedric Payne, senior director of ethics with the Campaign Legal Center, a government watchdog group. “If Carroll was involved in decisions benefitting GVP while he was at USAID, it is likely that he needed approval from the agency’s ethics officials. The public has a right to know if their public officials comply with conflict of interest laws.”

A USAID spokesperson said in a statement that Carroll never sought a waiver either from laws surrounding conflicts-of-interest while in a government job, or from laws regulating the revolving door.

“USAID does not have any record that Mr. Carroll sought clearance for any outside positions while he was still employed at USAID,” a spokesman said in an email.”USAID does not have any record that Mr. Carroll sought advice regarding whether a recusal was necessary or appropriate for any post-government employment negotiations in which he might have been engaging.”

Experts also raised concerns about Carroll appearing to leverage the prestige of his position at USAID to endorse the private organization he founded.

“There’s numerous conflict of interest laws that should be investigated here to ensure that Carroll didn’t violate the laws on the books,” said Scott Amey, general counsel for the Project on Government Oversight, a government watchdog group.

Carroll did not respond to a request for comment or to a request for the Global Virome Project’s tax records.

‘Which one did they prevent?’

A USAID spokesperson said that the group was first recognized as a nonprofit organization after Carroll left USAID. USAID has not provided the Global Virome Project with any further funding since it was formally incorporated, he said.

Still, some experts said that even if Carroll’s organization wasn’t formally recognized by the IRS as a nonprofit yet, his activities raise red flags.

“Even if you could find some loophole out of the criminal statute because GVP wasn’t technically a legal entity yet, this is a fundamental conflict of interest,” said Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington Chief Ethics Counsel Virginia Canter.

The USAID spokesperson did not respond to other questions about how much money the Global Virome Project received before its formal incorporation or whether Carroll should have sought an ethics waiver for his simultaneous work at USAID and GVP.

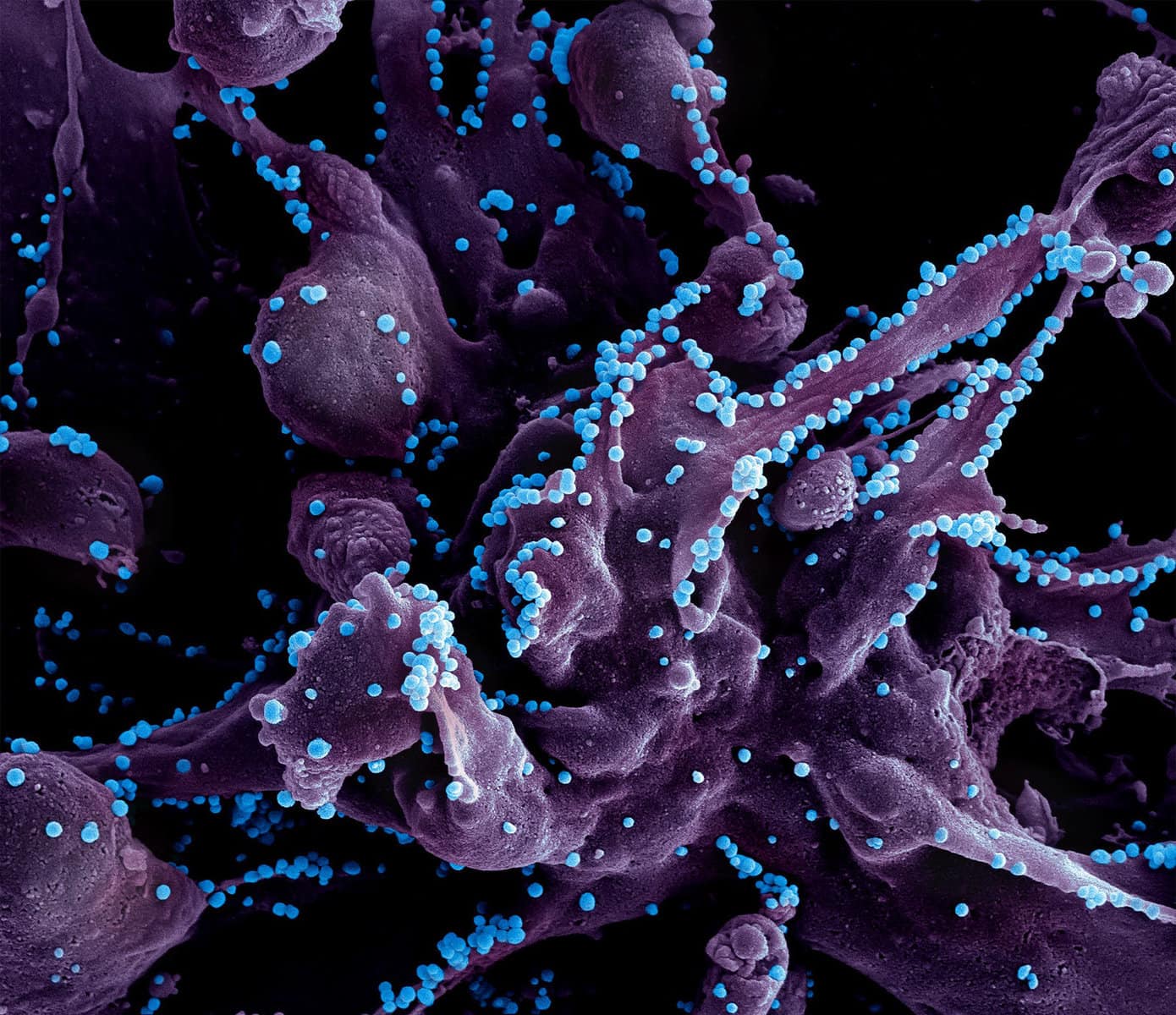

Meanwhile, even some experts who lean toward the theory that SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, first infected humans via two separate intermediate animal hosts, say the idea driving PREDICT and the Global Virome Project is far-fetched.

“If I thought there was a kind of ‘viral smoke alarm’ I would invest everything imaginable in that, but this project doesn’t give us that, ok?” said Michael Osterholm, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota, and a former advisor to the State Department on health security.

Deep knowledge about Zika and Nipah has still not led to proven vaccines against them, he said.

Osterholm said Carroll’s daring “Indiana Jones” image is not backed up by real payoffs for public health.

“Show me one thing they’ve done that has made a difference, where they could even make a case that they supposedly prevented a pandemic. Which one did they prevent?” he said. “Did they find anything that helped us with this coronavirus?”

Connections in Wuhan

Global Virome Project cofounder, secretary and treasurer Peter Daszak — president of another USAID contractor called EcoHealth Alliance — has come under Congressional scrutiny because of his work with the Wuhan Institute of Virology, including on so-called “gain-of-function” work that makes novel coronaviruses more dangerous in the lab. Carroll’s division at USAID funded the Wuhan Institute of Virology through EcoHealth Alliance.

Shi Zhengli, a top coronavirus researcher at the Wuhan lab, worked with Carroll’s PREDICT and was slated to work with the Global Virome Project.

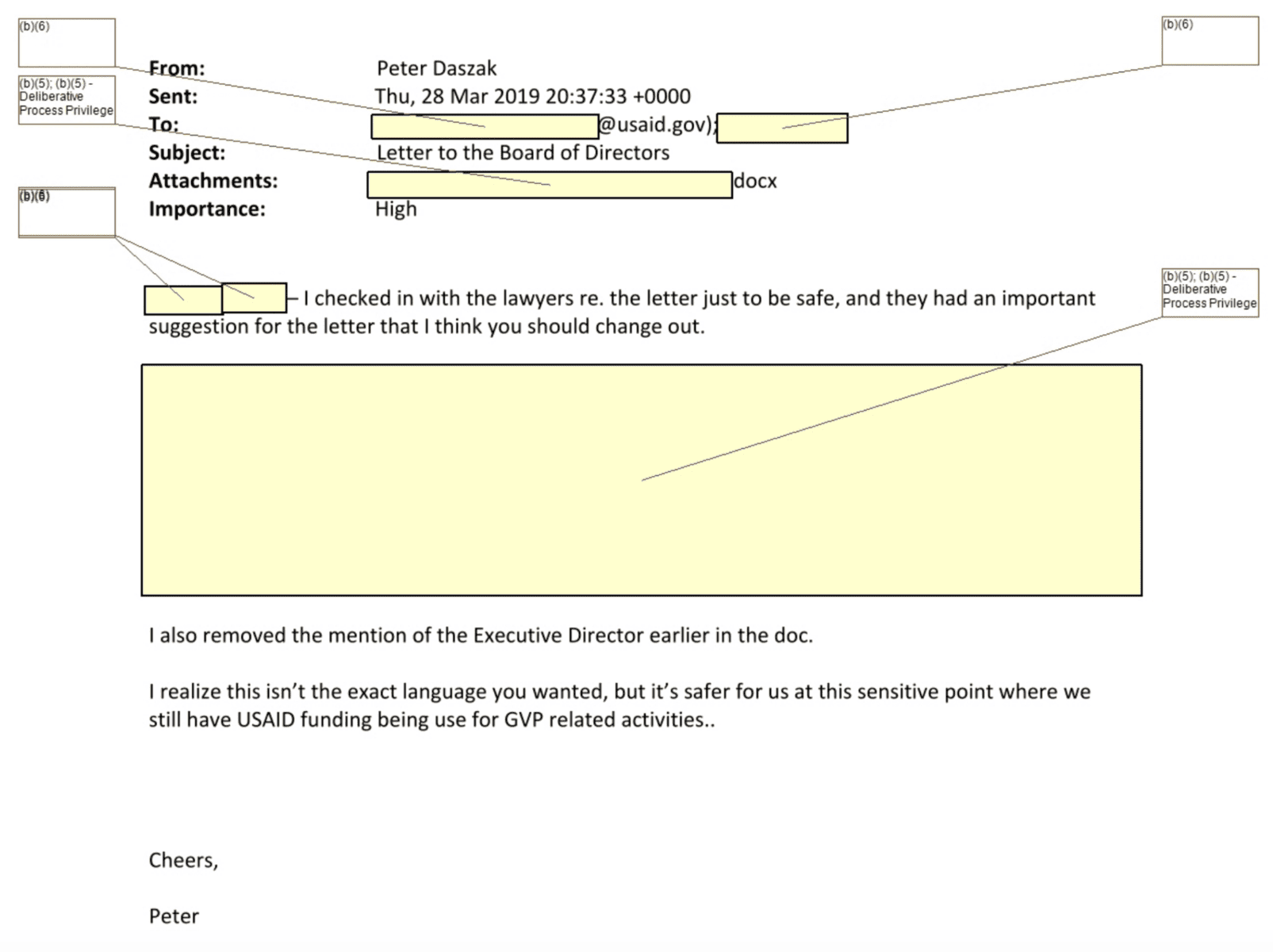

The emails demonstrate that there was significant correspondence between Carroll and Daszak about the Global Virome Project while Carroll was a USAID official and EcoHealth was receiving USAID funds.

In one March 2019 email, Daszak suggests that lawyers flagged the overlap in Carroll’s role.

“I realize this isn’t the exact language you wanted, but it’s safer for us at this sensitive point where we still receive USAID funding being [used] for GVP related activities,” Daszak wrote to Carroll.

The details are redacted.

Carroll pitches pricey virus collection plan with USAID funds

Carroll marshaled significant taxpayer funds to lay the groundwork for his pet project.

USAID funded Global Virome Project collaborators’ international trips as they made their pitch to potential investors.

In February 2017, USAID funded the stipend of Eddy Rubin, a member of the Global Virome Project board of directors, while he traveled in Beijing to meet with scientific staff at the U.S. Embassy there about China’s role, the so-called China National Virome Project.

Again in October 2018, USAID paid for three individuals to fly to Bangkok to pitch the Thailand Global Virome Project: EcoHealth Alliance fellow Alice Latinne, Metabiota, Inc. epidemiologist David McIver, and University of Missouri intellectual property expert Sam Halabi. The itineraries of Latinne and McIver included work for the Global Virome Project, but also included work for USAID’s PREDICT. But Halabi’s trip had no apparent relevance to USAID work.

China and Thailand were two of the five country partners that the Global Virome Project targeted in its first phase.

In addition, a cost-benefit analysis of the Global Virome Project was commissioned by Carroll and undertaken with USAID funds in August 2018. The precise costs are unclear, but the endeavor may have involved several cross-country flights by University of Washington economist Dean Jamison, the emails indicate.

And Cara Chrisman, a USAID official who worked under Carroll, was often looped in on logistical questions about the Global Virome Project.

Uncertain future

Critics of the Global Virome Project even include some virologists who are skeptical of the theory that posits research on novel coronaviruses in Wuhan could be related to SARS-CoV-2.

University of Sydney evolutionary biologist and virologist Edward C. Holmes, University of Edinburgh virologist Andrew Rambaut and Scripps Research virologist Kristian G. Andersen wrote in Nature in 2018 that the Global Virome Project is unlikely to predict pandemics because animal viruses so rarely cause epidemics in humans.

“Around 250 human viruses have been described, and only a small subset of these have caused major epidemics this century,” they wrote. “Advocates of prediction also argue that it will be possible to anticipate how likely a virus is to emerge in people on the basis of its sequence, and by using knowledge of how it interacts with cells (obtained, for instance, by studying the virus in human cell cultures). This is misguided.”

At the time, they pointed out that its cost would comprise roughly one fourth the entire budget for the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the U.S. agency that funds most viral research. And that is not accounting for the speedy evolution of certain viruses, which could quickly make the data collected outdated, they wrote.

More recently, Holmes again critiqued the idea of deep surveillance of viruses in wildlife in an editorial, even while underscoring the importance of regulating live animal markets.

Carroll and Daszak have defended the steep price tag of the Global Virome Project by comparing its projected spend to the devastating costs of a pandemic.

“Pandemics are estimated to cause an average of US $570 billion in economic damages per year to the global economy,” they wrote in 2018. “The Global Virome Project will cost U.S. $1.2 billion, which is less than 0.2 percent of this estimated loss.”