The State Department and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) strongly backed a controversial research project with China into novel viruses in 2019 even though it created new biosecurity risks, documents obtained through the Freedom of Information Act show.

The Global Virome Project (GVP) was designed to discover and catalog thousands of novel viruses that could spill over in nature or pose global biosecurity risks — estimated to be 500,000 viruses or more.

Among the project leaders were Shi Zhengli, a senior scientist with the Wuhan Institute of Virology, and her American collaborator, Peter Daszak. Sequencing for the GVP was to be led in part by BGI, China’s largest genomic sequencing company. Both the WIV and BGI have ties to the People’s Liberation Army. China’s Academy of Military Medical Sciences was also set to be a collaborator.

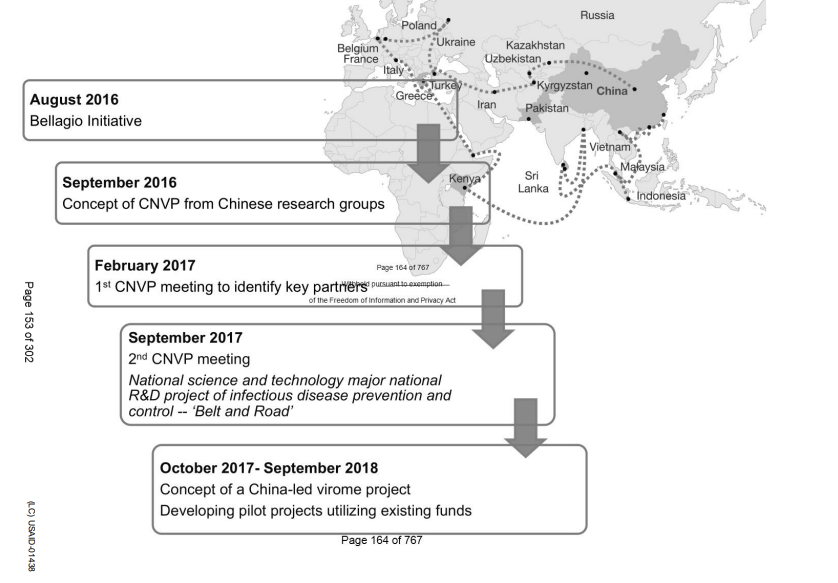

Hundreds of records obtained by U.S. Right to Know from Freedom of Information Act lawsuits show how the GVP was boosted by the State Department and underwritten by USAID as it got off the ground from 2016-2019. They also show that the U.S. forged ahead despite unanswered questions around who would own the data and whether Chinese partners would be transparent with the research. When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, the WIV’s library of coronavirus samples was unavailable for independent inspection. At least 11,051 samples were left in WIV freezers by USAID-backed scientists.

The documents give a window into the U.S. government’s aims in entering into high risk projects with the Wuhan lab. Officials hoped “health security” provided a noncontroversial opportunity for collaboration. The project also served the U.S. government’s desire for more cooperation on China’s work on infectious diseases and its Belt and Road Initiative, the records show.

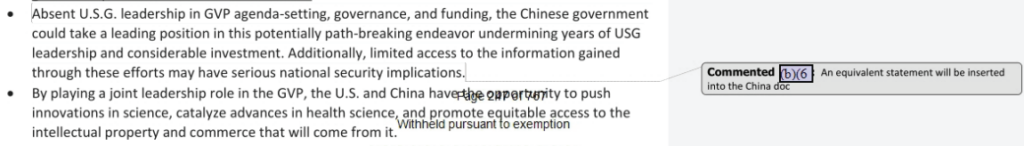

American institutions were told that if China undertook novel virus research without U.S. participation, it could pose a national security risk, according to a “draft pitch” from May 20, 2019, outlining the project. Chinese officials were told the same.

“Limited access to the information gained through these efforts may have serious national security implications,” it reads.

“While the GVP will have to navigate complex issues concerning sharing of specimens and data across national borders,” the pitch reads. “Absent U.S. leadership in GVP agenda-setting, governance, and funding, the Chinese government could take a leading position in this potentially path-breaking endeavor undermining years of [U.S. government] leadership and considerable investment.”

A comment on the draft states that “an equivalent statement will be inserted into the China doc” – the pitch translated and sent to Chinese institutions.

While the connection between the WIV and the National Institutes of Health has been well documented, the lab’s connections to State and USAID have been relatively overlooked. That’s likely because the money dried up for the GVP sometime after the pandemic’s outbreak, according to a March 2020 email released last week by the U.S. Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Pandemic.

USAID, which coordinates its budget with the State Department, underwrote the GVP as it got off the ground with $1.3 million, according to a letter by Sen. Roger Marshall, R-Kan. USAID also underwrote the “prototype” for the GVP, a similar novel virus collection and research project called PREDICT, with at least $210 million. The GVP was created by Daszak, the president of a nonprofit called EcoHealth Alliance, and two other leaders of PREDICT, epidemiologist Jonna Mazet of UC Davis, and Dennis Carroll, former director of USAID’s Emerging Threats Division.

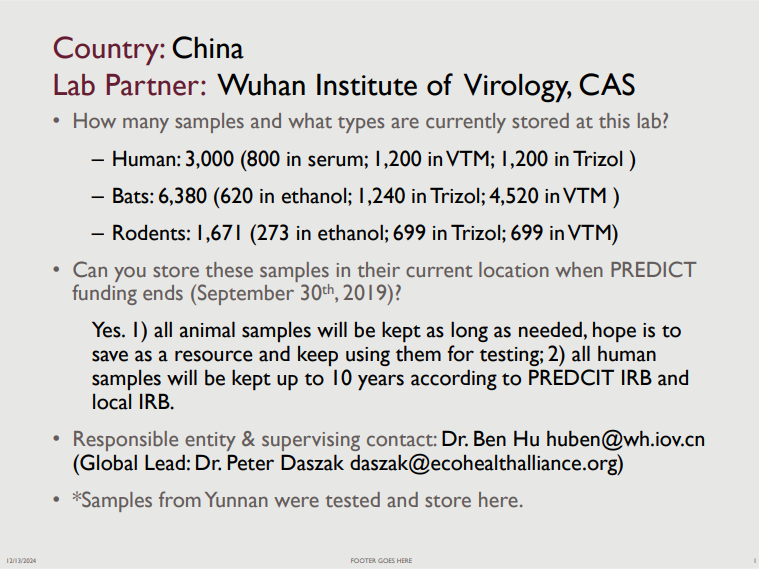

As PREDICT wound down and the resources were diverted to the GVP, a sample disposition plan was shared with USAID indicating that 6,380 samples from bats collected by PREDICT — as well as 3,000 human samples and 1,671 rodent samples — were left in WIV freezers. These include samples from Yunnan Province, where coronaviruses closely related to SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, circulate.

The WIV was excluded from eligibility (debarred) from federal funding for 10 years in September 2023 — the maximum number of years allowed by law — for its failure to turn over lab notebooks about its coronavirus experiments to its funders at the NIH. EcoHealth and Daszak are also under investigation by the Department of Health and Human Services for failures to properly oversee their collaborative research in Wuhan.

The benefits

Documents obtained from USAID and the State Department show the enthusiastic backing of the GVP, as well as glimpses of the biosecurity concerns swept aside in pursuit of the project.

Unclassified U.S. State Department correspondence from the American Embassy in Beijing strongly endorsed the GVP in 2017.

“It is encouraging that China, along with other countries, is ready to take what started as a U.S.-led initiative and proof of concept to a global scale,” according to a cable sent in September of that year and signed off by Terry Branstad, the former U.S. Ambassador to the People’s Republic of China.

American officials saw public health as a rich area for cooperation.

“[The Beijing] Embassy is very interested in this project as it is one of the areas that US and China can work together without much political confrontation,” wrote Ping Chen, the former National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases representative at the U.S. Embassy in Beijing, in an email dated September 2017 and released last week by the House Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Pandemic.

Other documents show strong support for the GVP within the U.S. Embassy in Beijing.

A map presented by Daszak in a February 2017 powerpoint shows plans to extend a “China-led Virome Project” across the world: from Kenya to Pakistan to Indonesia, with U.S. help. Project leaders aspired to work in West Africa, Central Africa, Southeast Asia and South Asia, internal notes show.

The State Department and USAID endorsed the project also in order to gain more insight into the risk of infectious disease spillover from animals to humans. EcoHealth had also pitched the Global Virome Project as useful for preventing biowarfare and lab accidents. The documents also show that officials were eager to learn about China’s foreign investments in infectious diseases.

The risks

The 2017 cable acknowledged that China’s independent funding for its arm of the project would need to be harnessed in a way that served “U.S. interests.”

“Shi Zhengli, a senior scientist at the Wuhan Institute of Virology, Chinese Academy of Sciences who studied mechanisms of transmission of SARS between species, stated that CAS has already allocated funding for GVP-related research,” the 2017 cable reads. “The Chinese government has shown a strong interest in the Global Virome Project and is not shy in funding projects where Chinese scientists will take a lead,” the cable states.

The Chinese Academy of Sciences, the Ministry of Sciences and Technology and National Natural Science Foundation of China were also poised to support the work through CAS funding.

“It is likely that the Chinese government will engage both with funding and with in-kind support, which will likely give China a large voice in GVP governance and data-sharing policies,” the cable reads, adding that it “will be important for the USG to remain engaged in significant ways with the GVP, to ensure that U.S. interests are adequately reflected in this effort…”

The cable also acknowledged that the tricky questions around the ownership of genomic data and viral samples had not yet been answered.

“Who will own the samples that are collected by many countries? Where will they be analyzed? Will all GVP data be freely available to the public? GVP expects to grapple with these questions very early, but it will take time for policies to be proposed and approved by many countries,” the cable reads.

The cable also strikes an uncertain tone about the reliability and transparency of BGI, which had committed to doing 30 percent of the project’s sequencing work.

“BGI’s commitment … to GVP’s values of open, free access to data has not been officially stated,” the cable acknowledges.

BGI “did not provide details on how that sequencing would take place or where the subsequent data would be housed,” the cable reads. “Note: BGI has enjoyed significant funding from the Chinese government.”

One factor that encouraged confidence in BGI was its involvement 30 years prior in the Human Genome Project, led by former director of the National Institutes of Health Francis Collins.

“Its current leader, Yang Huanming, was instrumental in China’s involvement in the Human Genome Project in the 1990s, and is a proponent of sharing data,” the cable reads.

Yet Collins has faced criticism for not prioritizing biosecurity and an ignorance of the Biological Weapons Convention while at NIH.

In the seven years since the 2017 cable proposing the collaboration, BGI’s ambitions have come into fuller view, raising the hackles of the U.S. intelligence community. BGI used pregnancy tests to collect human DNA data, which was then diverted to the People’s Liberation Army, according to a 2021 Reuters report.

Chen, the NIAID representative in Beijing, paid a visit to the Wuhan Institute of Virology’s new maximum security laboratory complex in October 2017 — one month after the cable endorsing the GVP — and was not permitted inside the laboratories.

Still, American and Chinese institutions continued to collaborate on virus hunting work.

The documents used in this story were obtained through Freedom of Information Act lawsuits against the State Department and USAID. You can read these and all of our documents in our biohazards investigation here.