As pesticide companies struggle to cap legal payouts to plaintiffs who claim they were injured by Roundup and other products, money from two political committees affiliated with major pesticide manufacturers has surged into state-level politics.

In recent years, total contributions to state legislators have reached hundreds of thousands of dollars.

By contrast, in 2016, the two leading agrochemical companies gave less than 5 percent of contributions to candidates at the state level. This year, however, state candidates received about 30 percent of contributions to candidates from PACs for employees of Bayer, which is headquartered in Leverkusen, Germany, and Corteva, which is based in Indianapolis.

In particular, legislators in California, New Jersey, Iowa, Idaho, Illinois, Hawaii, North Carolina and Texas have benefited from the largesse of pesticide company employee political action committees during the last two years, according to data from the Federal Election Commission.

In many cases, individual candidates received small amounts from the PACs, such as $500 or $1,000, but a campaign finance expert said that all donations count.

“Suppose you have two people outside your office who want to go to lunch, and you only have time for one,” said Bob Stern, former general counsel of the California Fair Political Practices Commission. He said that typically, a politician would be more likely to go to lunch with the one who has made the donation.

“Nobody wastes money,” Stern said. “There is a big reason they’re making their contribution. It’s not a charity.”

Nobody wastes money. There is a big reason they’re making their contribution. It’s not a charity.

– Bob Stern, former general counsel of the California Fair Political Practices Commission

Representatives from the companies did not answer questions about the specific political priorities of their employee committees in statehouses. Rather, they noted that the PACs allow employees to support legislators who align with the companies’ interests.

In many of the targeted states, legislation has been introduced that would limit companies’ payouts in lawsuits that find that consumers, groundskeepers and farmers were sickened or killed by pesticides.

Other recent issues in these states include bans on neonicotinoids and other pesticides, as well as proposals to prevent states from setting higher standards for labeling on the uses of pesticides that exceed the standards set by the federal Environmental Protection Agency.

In most states, the pesticide company employee PACs contributed to a combination of legislative leaders and emerging leaders, with emphasis on legislators who chair agricultural and environmental committees.

“They’re definitely all people who are close to leadership,” said Anne Frederick, executive director of the Hawaii Alliance for Progressive Action, a nonprofit organization in Hawaii, after she reviewed the list of recipients.

Contributions at the state level from employee PACs from Bayer and Corteva have quintupled in recent years.

In the 2016 and 2018 election cycles, which cover two-year periods, the Bayer employee PAC gave less than $25,000 to state and local candidates. During the election cycles ending in 2020, 2022 and 2024, those contributions totaled between $70,000 and $144,000 per cycle.

The Corteva employee PAC gave zero dollars to state and local candidates in the 2016 and 2018 cycles. In the years since, the PAC donations at the state and local levels totaled between $9,800 and $48,000 per election cycle.

The campaign contributions represent one segment of political activity that surrounded pesticide-related legislation. In some cases, companies’ efforts focused on lobbying, which is disclosed separately. Another form of influence can come by way of so-called “dark money,” a mechanism by which nonprofits and shell companies donate to super PACs without disclosing the individual donors behind the contributions. For that reason, tallies of the most direct form of political influence – individual campaign contributions – may present an incomplete picture of corporate involvement in legislative processes.

On the subject of employee PACs, a prepared statement from Bayer said, in part, “Like many organizations, companies and industries, BayerPAC engages and participates in the political process at both the federal and state level to help support our industry, customers and business.”

A prepared statement from the Chinese state-owned company Syngenta said, “SyngentaPac is a 100% employee-funded organization that allows Syngenta’s American employees – Americans working for American agriculture – to proudly support legislators who align with our mission to support the nation’s hardworking farmers. . . .

“We donate to campaigns of legislators who are strong advocates for American agriculture – something we need more of in Congress and in statehouses across the country. Our lobbying reporting reflects our efforts to educate these policymakers on Syngenta’s mission to support American farmers.”

A statement from BASF outlined how the American campaign contribution and disclosure system works, but offered no detail on the PAC’s political priorities, and representatives from Corteva did not respond to emailed questions.

Companies seek to limit damage awards in court

In the last year, massive lobbying campaigns by pesticide companies at both the state and federal levels have pushed for mechanisms that would limit damages awarded by courts in pesticide injury lawsuits.

Bayer, in particular, has struggled under the weight of injury awards to plaintiffs in cases involving Roundup, an herbicide that has been the target of more than 11,000 lawsuits because of links to cancer. According to a fact sheet by U.S. Right to Know, “the scientific literature and regulatory conclusions regarding cancer links to glyphosate and glyphosate-based herbicides show a mix of findings, making the safety of the herbicide a hotly debated subject.” While Bayer has maintained that glyphosate is safe when used correctly, scientific research has linked exposure to non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Also, in 2015, the International Agency for Research on Cancer classified glyphosate as “probably carcinogenic to humans.”

In comments for the company’s 2023 annual report, executives reported that the company’s performance is suffering because of significant losses in legal judgments. Bayer’s provision for the glyphosate litigation totaled $6.3 billion, as of Dec. 31, 2023, from lawsuits over Roundup.

Bayer’s stock price is down 37 percent in the last year.

The Washington Post reported this year that Bayer has lobbied the U.S. Congress to pass the Agricultural Labeling Uniformity Act, which would prohibit states and local governments from imposing labeling requirements on pesticides that differ from federal labeling requirements.

The Post reported that the federal legislation “aims to prevent local governments and courts from being able to ‘penalize or hold liable any entity for failing to comply’ with rules for pesticide warnings that differ substantially from what the federal government already mandates.”

In Iowa, one of these bills was initially presented by Bayer’s representatives as “an innocuous labeling bill” but, upon further examination, turned out to be a measure that would provide complete immunity for any chemical companies in all pesticide-related lawsuits, said Andrew Mertens, executive director of the Iowa Association for Justice, a trial lawyers group.

Opposition mounted in part, he said, because “it represents a forfeiture of corporate responsibility over to the federal government.”

A lot of Iowa legislators – particularly conservative lawmakers – had a hard time with this idea, Mertens said, because “not only would the individual rights of their constituents be eliminated, but private corporate responsibility would be forfeited over to the federal government, which they frankly don’t trust.”

“Not only would the individual rights of their constituents be eliminated, but private corporate responsibility would be foreited over to the federal government, which they frankly don’t trust.

– Andrew Mertens, executive director of the Iowa Association for Justice, on “failure to warn” legislation

Rob Faux, communications manager for the nonprofit Pesticide Action Network, said that he wouldn’t be surprised to see liability-limiting legislation – known as “failure to warn” laws – crop up nationwide.

“I think you’ll find that the ‘failure to warn’ legislation will take form in probably 10 or 20 different states. It might not surprise me if every state had cookie-cutter legislation appear and probably won’t go anywhere,” he said.

Under federal law, corporations are not allowed to donate money directly to candidates, and PACs that receive contributions from employees distribute donations to candidates and political committees on their behalf.

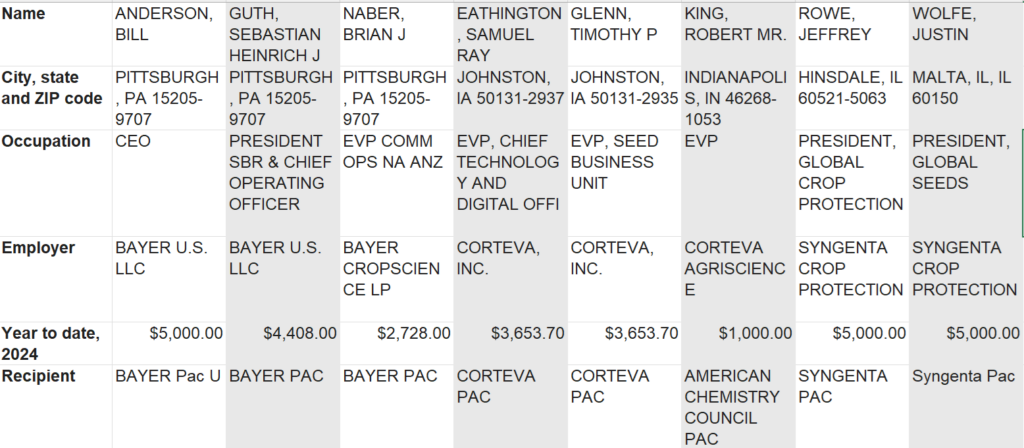

In four political action committees associated with pesticide company employees, top company officers exclusively made political donations to the employee PACs.

Here is a partial list of those executives and their donations, according to campaign contribution records from the Federal Election Commission:

Pesticide company employee PACs favor Republicans by nearly 2-to-1

At the federal level, pesticide companies’ employee committees have donated the highest proportion of money to Republican candidates, by a ratio of nearly 2-to-1.

Over eight years, employee PACs for Bayer, Corteva, Syngenta, FMC and BASF have donated 62 percent of federal candidate contributions to Republican candidates and 38 percent to Democrats, according to an analysis of FEC data through Oct. 17. For federal candidates, the PACs gave Democrats $2.3 million during that period and Republicans $3.7 million.

Democrats received $2.2 million during that period, and Republicans received $3.6 million, according to campaign contribution records.

State-level donations and issues

U.S. Right to Know assembled a list of legislators who received funds from agrochemical company employee PACs by state, along with summaries of major pesticide-related legislation that has passed or is pending. With the exception of data from Missouri, all donations in the list come from the 2023-24 election cycle.

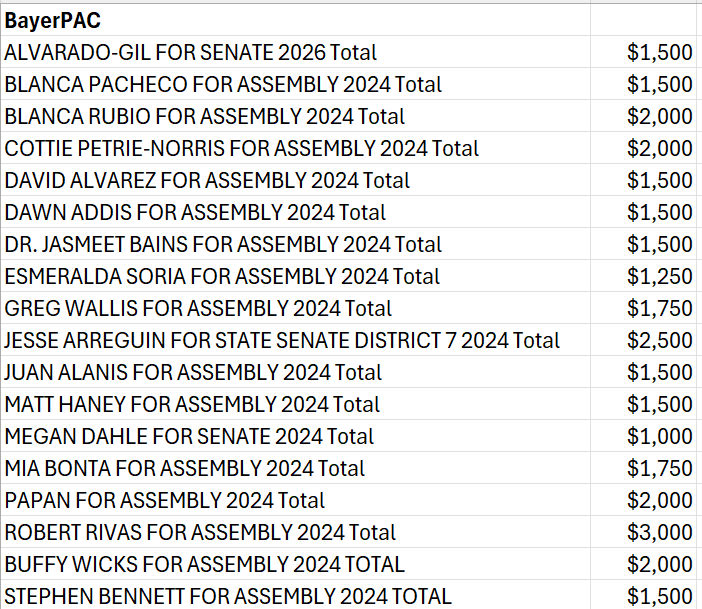

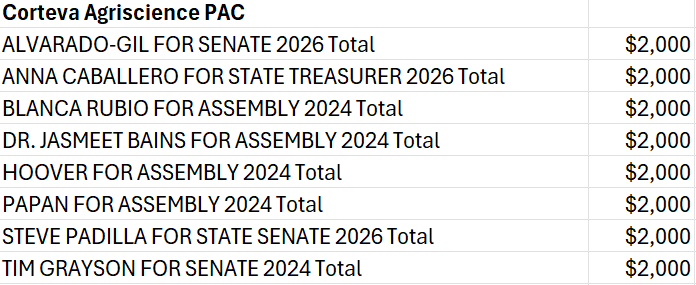

California

In California, major pesticide legislation in recent sessions included bills to ban the herbicide paraquat, to expand safety reviews of neonicotinoid pesticides in non-agricultural uses, to include private schools in notifications for pesticide use at school sites and to speed up pesticide registrations.

All of those bills were signed by California Gov. Gavin Newsom.

Nonetheless, Jane Sellen, co-director of Californians for Pesticide Reform, saw the hand of industry in the final language of the bills.

The paraquat ban, she said, “is not a ban. It started out as a ban . . . and then it got watered down to nothing.”

The outcome: A state agency will now re-evaluate its safety.

On the new law to speed up the pace of pesticide registrations, Sellen is equally skeptical about the outcome.

“They’ve got a backlog of about 80 that they’ve prioritized,” she said. “They’ll catch up in your great-great grandkids’ lifetime.”

Here is the list of California legislators who received donations from the employee PACs of agrochemical companies, according to FEC data:

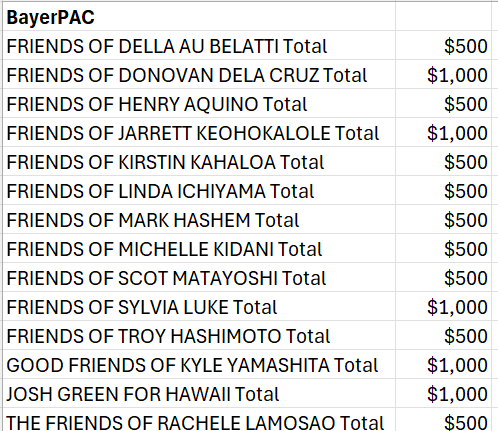

Hawaii

Because of its year-round growing season, Hawaii has been a site for experimental crops for agrochemical companies for years. Companies develop parent seed there.

“We’ve called Hawaii ground zero for experimental field trials,” said Frederick of the Hawaii Alliance for Progressive Action, or HAPA.

In recent legislative sessions, HAPA and other environmental groups have advocated for improved disclosure of restricted-use pesticides, increased buffer zones around schools and other sensitive areas, and the re-classification of neonicotinoids as restricted-use pesticides to improve tracking of their use.

“We continue to advocate for some of these provisions that the community’s been asking for since 2006 or 2008,” Frederick said.

She said that most bills on these issues died without hearings in the Legislature’s last session.

When Frederick reviewed the list of legislators who had received contributions from Bayer, which maintains a large presence in the state, she said the recipients reflected the power players and emerging players in the Legislature.

“Because there has been so much pushback on industry here, they’re trying to build bridges,” she said.

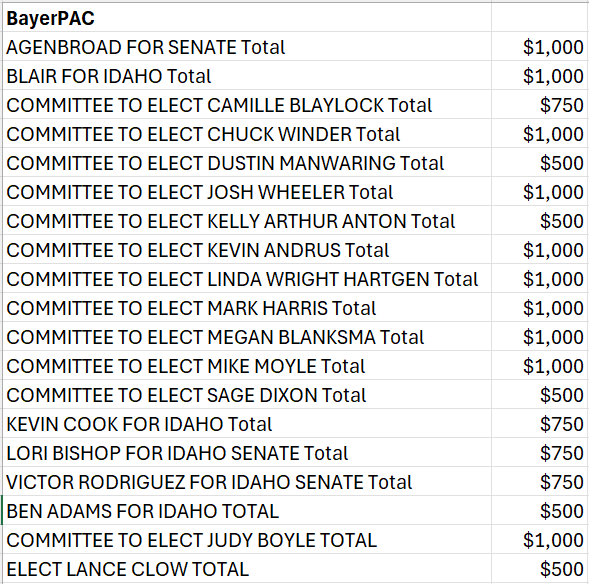

Idaho

The pesticide manufacturers started their political push into the states in recent years in Idaho, which was targeted by extensive campaigning and lobbying with the introduction of a bill to limit damages in lawsuits.

The Idaho Statesman published a detailed report on the campaign called “How Idaho became the target of an influence campaign to protect pesticide companies.”

According to the Statesman, “in the three months of the legislative session, the push from the industry brought tens of thousands in public advertisements, thousands of dollars of campaign donations, free bottles of Roundup, and private calls with Bayer’s CEO — all aimed at convincing legislators to seal off prominent herbicides like Roundup from most liability lawsuits.”

The newspaper reported that despite the “full-court press,” the bill drew a bipartisan coalition of lawmakers and failed by four votes.

Lawmakers and analysts in the state expect the liability-limiting bill to reappear, according to the newspaper.

Here are Idaho legislators who received money from agrochemical company employee PACs:

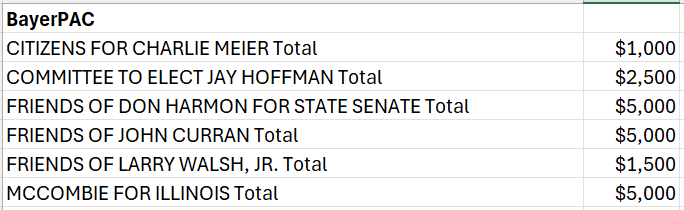

Illinois

The Illinois legislature recently passed bills that require notifications when pesticides are sprayed at schools and to increase penalties for human exposure to pesticides.

New penalties for exposure in the state break down like this:

- If one to two humans are exposed, the penalty will be $500 per person.

- If three to four humans are exposed, the penalty will be $750 per person.

- If five or more humans are exposed, the penalty will be $1,250 per person.

Eliot Clay, the land use programs director for the nonprofit Illinois Environmental Council, said that legislative priorities for the next session will probably include a ban on neonicotinoid pesticides, the increasing of setback distances at schools and parks during the use of pesticides, and a ban on ester formulations in herbicides.

As far as the recipients of donations from the Bayer employees PAC, he said that the dollars went to the leaders of political parties and the agriculture committee.

“The names you gave all make sense,” Clay said. “These all seem like very strategic donations. They didn’t come up with that in a vacuum. That’s very thought-through.”

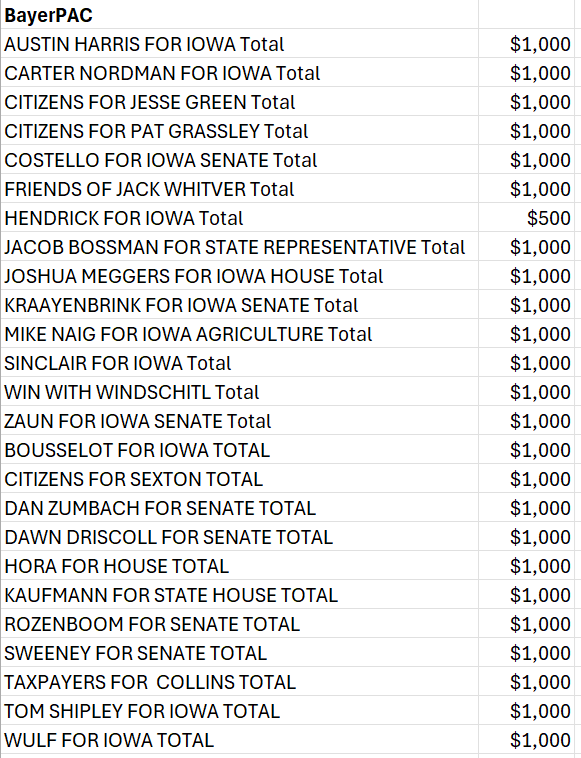

Iowa

Along with legislators in Idaho and Missouri, lawmakers in Iowa introduced and defeated one of the first bills in the country that would limit pesticide companies’ damages in injury cases.

Rob Faux, an Iowa farmer and spokesman for the Pesticide Action Network, said that “Iowa’s right on the forefront of it, and there’s a lot of money, especially from Bayer, getting pushed around.”

After complicated legislative maneuvering, the bill failed.

Mertens, of the trial lawyers association in Iowa, said the legislation failed, in part, because it had not passed in any other state and would leave Iowans exposed.

“Because this has never passed anywhere, and this isn’t the law of the land anywhere – this idea of immunizing chemical companies, the idea . . . is that Iowa farmers and ag workers would be alone in not having the right to seek justice.

“If you lived anywhere else in the country and developed cancer from one of these products, you could seek justice,” Mertens said, “but not if you’re an Iowan.”

At one point during the fight over the bill, Faux said, because Iowa has “a number of farmers” involved in lawsuits over paraquat, the bill was amended so that Syngenta’s liabilities would remain, but that liabilities for other companies – particularly Bayer – would be limited.

Legislators changed the exemption from liability in the bill to exclude ChemChina (Syngenta).

“That was a very, very telling move,” Faux said, “because it was clear that this legislation is for the benefit of the particular company.”

By that “particular company,” he meant Bayer.

Faux said he was disappointed to hear some of the names of the legislators who had received campaign contributions from pesticide industry employee PACs, particularly House Speaker Pat Grassley and state Secretary of Agriculture Mike Naig.

“I also would think that some of these individuals, if they wanted to maintain some image of balance, and integrity, I would think they would say no.

“This is me, applying my own morals to politics, which is probably not a fair way to look at things. . . . Maybe it’s unrealistic of me to expect that,” Faux said.

Mertens said he was “a hundred percent sure” that the “failure to warn” legislation would be re-introduced in Iowa.

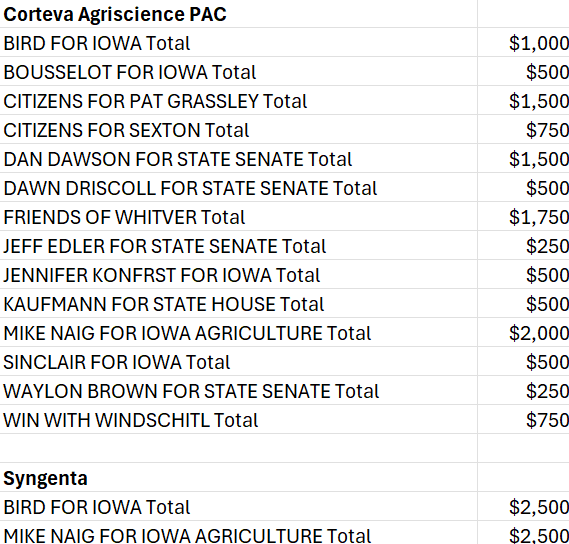

Here is the list of Iowa legislators who received campaign contributions:

Missouri

In the Missouri Legislature, legislation to limit liabilities in pesticide injury cases was defeated by trial attorneys who built an alliance with GOP lawmakers in the Missouri Freedom Caucus, a group that is “known for bringing the state Senate to a halt,” according to reporting from the Missouri Independent.

A Bayer attorney told the Independent that the company finds a “patchwork” of labeling that varies from state to state burdensome.

In an unconventional alliance, the Missouri Freedom Caucus and trial lawyers pushed back against “powerful agricultural and business organizations,” and the bill failed to advance, the Independent reported.

In October, the BayerPAC gave $20,000 to the Bayer LLC US Missouri PAC, which is listed by the FEC as a non-affiliated state PAC.

The headquarters of Bayer Crop Science – formerly Monsanto – is in St. Louis.

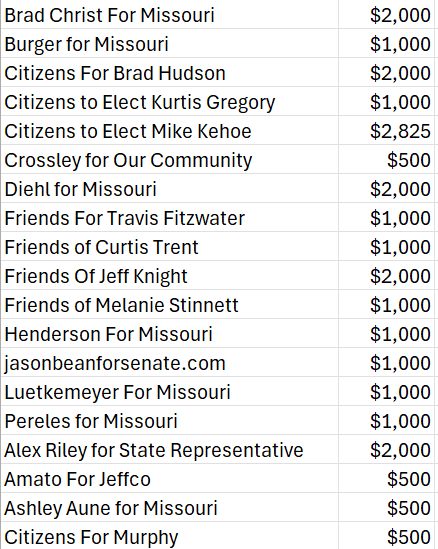

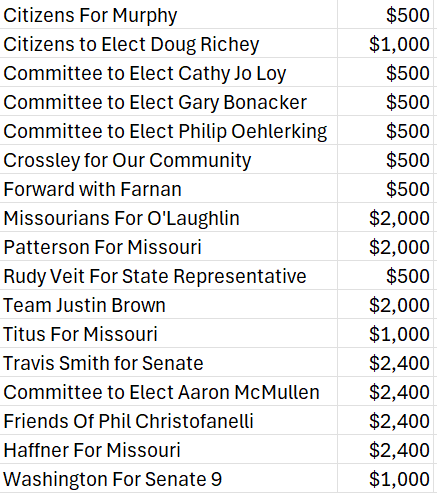

Here are disbursements from Bayer’s PAC in Missouri in 2024, according to filings with the state’s ethics commission:

New Jersey

In recent years, New Jersey lawmakers banned neonicotinoid pesticides for non-agricultural uses.

Jason Davidson, senior food and agriculture campaigner for the nonprofit Friends of the Earth, said that he is not aware of new pesticide-related bills in the state, but that agrochemical company employee PACs would likely prefer to maintain a presence in the state’s politics.

“Absolutely New Jersey is a state where the pesticide industry has interests,” Davidson said.

Bayer’s U.S. headquarters is in Whippany, N.J. Further, dozens of chemical companies run manufacturing plants in New Jersey.

In terms of the recipients of campaign contributions, Davidson described them as “a mix of leadership, definitely a mix of environment committee and health committee. That’s what stands out.”

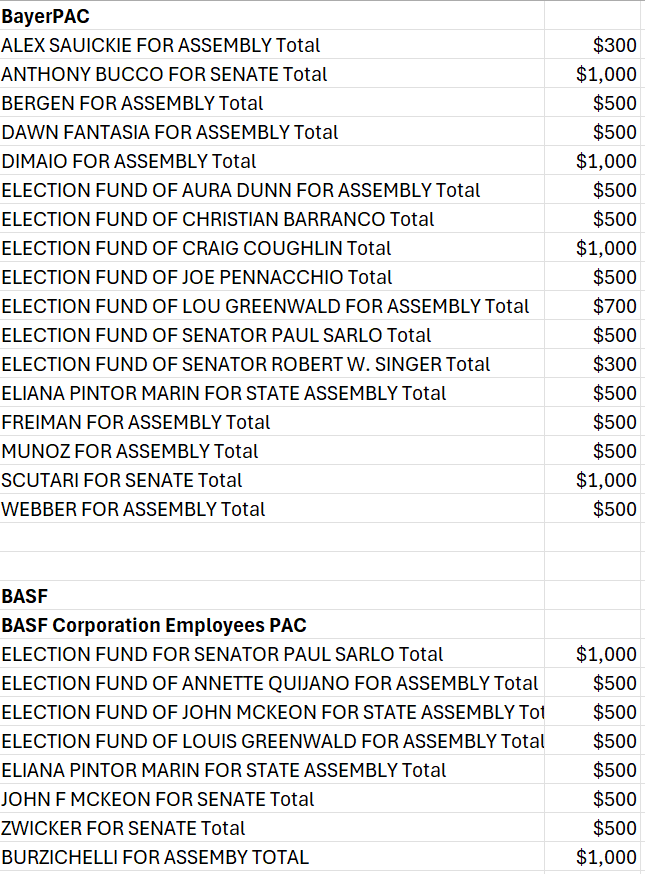

Here are legislators who received donations from pesticide company employee PACs.

North Carolina

No pesticide-related legislation was introduced in the recent session of the North Carolina Legislature, but Kendall Wimberley, a policy advocate for the nonprofit Toxic Free North Carolina, said that the state may soon be targeted for “failure to warn” legislation to limit liabilities in pesticide injury cases.

“I wouldn’t be surprised if we see that next year,” Wimberley said. “I do think it might come up. I’m worried about it for next year, for sure.”

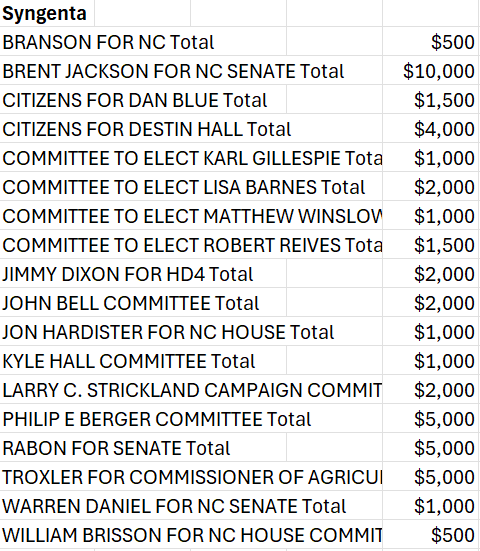

The state’s lawmakers have been particularly targeted by the employee PAC for Syngenta, which makes paraquat, a pesticide that has produced nearly 6,000 lawsuits nationwide. Also, Syngenta’s U.S. headquarters is in Greensboro, N.C.

As for the recipients of contributions, Wimberley said that “a lot of those names are the big names.”

“We have a decent number of legislators in North Carolina who are also farmers,” she said, “and they are involved in Big Ag.”

Here are the North Carolina legislators who have received contributions from a pesticide company employee PAC:

Texas

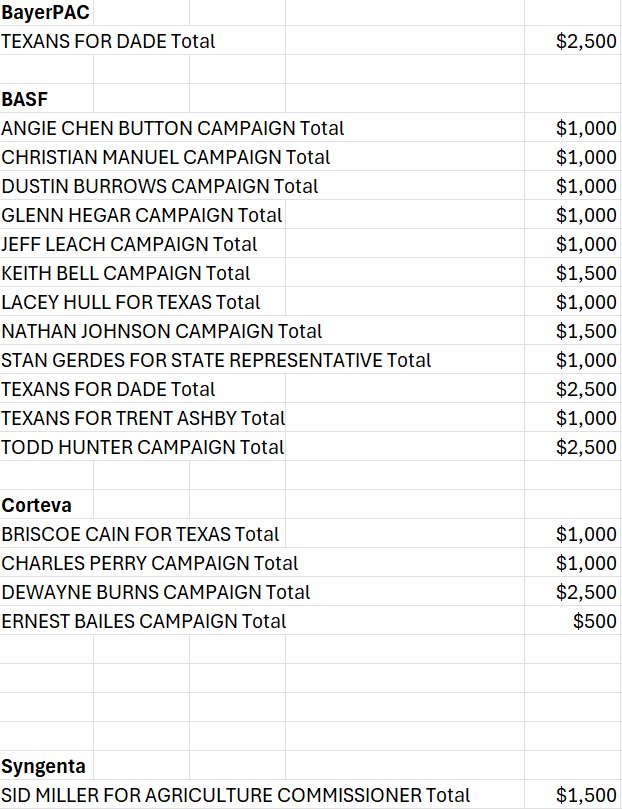

Texas politicians received $25,000 contributions from BASF and other pesticide company employee PACs in the last session.

A bill search of legislation introduced in the last session failed to turn up any pesticide-related legislation.

Rob Faux, communications director of the Pesticide Action Network, said that limitations on use of the ester formulations found in herbicides may come up in the state.

Here is the list of donations in Texas.