A scientific study that regulators around the world relied on for decades to justify continued approval of glyphosate was quietly retracted last Friday over serious ethical issues including secret authorship by Monsanto employees – raising questions about the pesticide-approval process in the U.S. and globally.

The April 2000 study by Gary Williams, Robert Kroes and Ian Munro – which concluded glyphosate does not pose a health risk to humans at typical exposure levels – was ghostwritten by Monsanto employees, and was “based solely on unpublished studies from Monsanto,” wrote Martin van den Berg, co-editor-in-chief of Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology. It also ignored “multiple other long-term chronic toxicity and carcinogenicity studies” that were available at the time.

Some of the study authors may also have received undisclosed financial compensation from Monsanto, he noted. Because of these problems, the editors “lost confidence in the results and conclusions of the article,” van den Berg wrote.

The retraction came years after internal corporate documents first revealed in 2017 that Monsanto employees were heavily involved in drafting the paper.

“What took them so long to retract it?” asked Michael Hansen, senior scientist of advocacy at Consumer Reports. “The retraction should have happened right after the documents came out.”

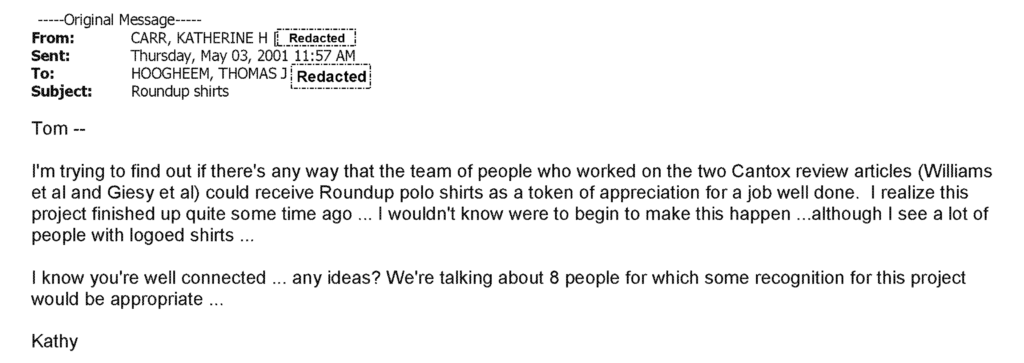

In one email from 2001, Monsanto scientist Katherine Carr asked if the “team of people” at Monsanto who worked on the Williams paper “could receive Roundup polo shirts as a token of appreciation for a job well done.”

Flawed paper was foundational for regulatory approval

While Monsanto scientists congratulated each other, glyphosate use was surging around the world; it is the most used herbicide in history. And the Williams paper played a key role in its continued acceptance as safe to use.

“Government documents from public health agencies around the world … cite this ghostwritten paper without caveat even after the 2017 revelations, affecting policy and shaping public perception of glyphosate’s safety,” wrote researcher Alexander Kaurov and Harvard historian Naomi Oreskes in an August article in Undark.

The ghostwritten paper “exerted considerable influence over two decades, shaping public understanding, scientific discourse and policy decisions,” Kaurov and Oreskes wrote in a September 2025 paper examining the influence of the now-retracted work.

The ghostwritten paper is in the top 0.1% of citations among academic papers discussing glyphosate, they found in their review; and the vast majority of policy and governance documents citing the paper “referenced it uncritically.”

These findings “underscore the need for stricter journal policies to screen and retract ghostwritten papers, in order to safeguard science integrity, as well as public health and safety,” Kaurov and Oreskes wrote.

So why did Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology wait until November 2025 to retract the paper?

Editor-In-Chief van den Berg, who has been the journal’s top editor since 2019 and is based in the Netherlands, told U.S. Right to Know via email: “it simply never ended (up) on my desk being at first primarily a U.S. situation with litigation. The paper of Oreskes triggered it this summer and these authors made an official request and complaint.”

He added, “If you have more papers regarding roundup published in RTP with possible problems, let me know.”

Longstanding problems at journal undermine regulatory system

The retraction exposes the flaws of a regulatory system that relies heavily on corporate research, and an academic publishing system that is often used as a tool for corporate product defense.

Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology, which is the journal of the International Society of Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology, has a “long, and damning history,” wrote journalist Paul Thacker in a 2017 article in Pacific Standard. He called RTP “the academic journal that corporations love.” David Michaels, a former head of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, and a public health scientist who studies corporate manipulation of science, described it in the article as, “a vanity journal that publishes mercenary science created by polluters and producers of toxic chemicals to manufacture uncertainty about the science underlying public-health and environmental protections.” As far back as 2002, critics complained about conflicts of interest at the journal, lack of transparency, poor editorial oversight and a bias in favor of industry.

But the problem goes deeper than one journal, as Thacker noted: “Corporations regularly buy academics to do their bidding, recasting industry talking points to create the beginnings of an alternative scientific canon.”

In the case of glyphosate, researchers and journalists have documented at length the many ways Monsanto manipulated the scientific record, influenced regulatory agencies, interfered in the peer-review process and used deceptive tactics to shape how regulators and the public view glyphosate.

Our own examination of the Monsanto Papers, published in the 2022 Merchants of Poison report, details how Monsanto and Bayer (which purchased Monsanto in 2018) used academics as a key part of their product-defense strategy for glyphosate, and paid front groups and other allies to attack journalists and scientists who raised concerns about glyphosate.

Bayer seeks reprieve

The retraction of a “hallmark paper in the discourse surrounding the carcinogenicity of glyphosate and Roundup,” as van den Burg described it, comes as Bayer is pleading for help from politicians and courts in its bid to evade liability in thousands of lawsuits brought by farmers and groundskeepers who claim glyphosate-based Roundup weedkiller caused them to develop cancer.

On Dec. 2, President Donald Trump’s administration stepped in to help Bayer, urging the U.S. Supreme Court to review the company’s immunity plea. The Department of Justice filed a brief arguing that people shouldn’t be able to sue Bayer in state courts for failure to warn them about the cancer risk of glyphosate-based Roundup herbicides. The news pushed Bayer’s shares to the highest level in more than two years.

The administration’s position has angered many supporters of Trump’s “Make America Healthy Again” (MAHA) constituency. “A deep betrayal today,” wrote Kelly Ryerson, who writes under the name Glyphosate Girl, posted on Instagram. “Why does every single administration continue to commit to poisoning us? … Don’t these people have families themselves?”