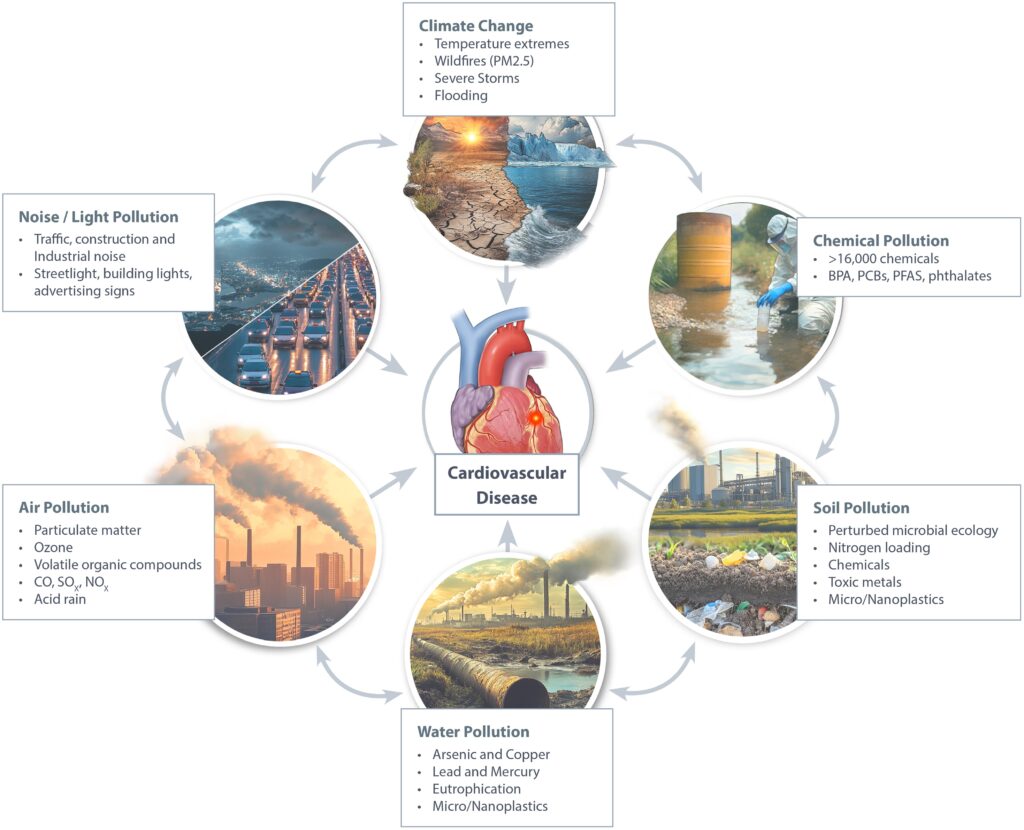

Cardiovascular disease—the world’s leading cause of death—is increasingly driven by polluted air, toxic chemicals, plastics, noise, and extreme temperatures, according to a sweeping new review in Cardiovascular Research that calls for stricter environmental regulations to protect public health.

Heart attacks, strokes, arrhythmias, and heart failure killed more than 20 million people in 2021, accounting for nearly one-third of all global deaths. The new analysis by a team of international scientists found increasing evidence that hazardous exposures are a major culprit in millions of these deaths worldwide each year, especially among vulnerable populations.

Air pollution, the most significant environmental risk, contributes to approximately 8.3 million deaths annually, with more than half due to cardiovascular disease (CVD), while two million people lost their lives in 2019 due to chemical exposures from contaminated soil and water.

While these drivers may appear unrelated, they are all forms of pollution—particularly from industry-produced toxins. Chemicals used in pesticides and phthalates in plastics, for instance, have been linked to heart damage and increased cardiovascular disease risk.

Meanwhile, fine particulate matter (PM2.5)—particles less than 2.5 micrometers in diameter, primarily from fossil fuel emissions—can worsen and contribute to the development of cardiovascular disease. Tiny particles can enter the lungs and bloodstream, causing cell damage, blood vessel injury, and atherosclerosis (narrowing and hardening of arteries), all of which contribute to a higher risk of blood clots, heart attacks, and strokes.

Theoretically, a complete phaseout of fossil fuels could prevent up to 82% of all avoidable deaths from human-caused air pollution, the researchers found.

“This comprehensive review…underscores the reality that environmental risk factors are major but insufficiently appreciated risk factors for CVD,” they said. “The evidence underscores the urgent need for targeted public health interventions and policy actions. Individual interventions and behavioral change are not sufficient to address these risks.”

As central drivers of the global cardiovascular disease epidemic, chemical pollutants should be treated as seriously as traditional health risk factors such as smoking, poor diet, and lack of exercise, the researchers said. Tobacco smoking caused 7.7 million deaths worldwide in 2019, a Lancet study showed.

“These factors contribute to a global disease burden, necessitating immediate and coordinated action at a societal level across disciplines and policy sectors,” the authors said.

Pollution and toxic chemicals fuel cardiovascular disease

Scientists in the U.S., U.K., Germany, Denmark, and Spain conducted the review. Its highlights include:

- Air pollution contributed to 8.3 million early deaths, with nearly 60% directly linked to heart disease, making it the second-leading global risk factor for death after high blood pressure (hypertension). Both short- and long-term exposures to polluted air are tied to hardened arteries, high blood pressure, abnormal cholesterol, strokes, and sudden cardiac events.

- Every 5 micrograms per cubic meter increase in annual PM2.5 was linked to a 13% rise in acute coronary events, while each 10 microgram increase in PM2.5 and PM10 was tied to higher rates of hospitalization and death from heart failure. Even in areas with relatively low levels of pollution, such as Tasmania, spikes in PM2.5were associated with rising cases of heart failure.

- Patients with microplastics (MNPs) in arterial plaques faced a 4.5-fold higher risk of heart attack, stroke, or death within three years. Micro- and nanoplastics may damage blood vessels by triggering cell damage and inflammation, harming blood vessels, and accelerating cell aging—mechanisms central to CVD, preclinical studies showed. They also may act as carriers for toxic chemicals such as phthalates, bisphenol A (BPA), PFAS, and heavy metals, amplifying cardiovascular risk. In addition, they may promote clotting and red blood cell damage, further raising the likelihood of complications.

- Endocrine-disrupting chemicals such as PFAS, BPA, and dioxins increase cardiovascular risk by disrupting metabolism, triggering cell and tissue damage, and fueling inflammation. BPA has been linked to higher rates of heart disease, hypertension, and heart failure, while PFAS contributes to artery disease. Widely used organophosphate pesticides are tied to dangerous heart rhythms, and other pollutants, including polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs, chemicals formed when coal, oil, gas, wood, garbage, or tobacco are burned), are also increasingly associated with cardiovascular diseases.

- Lead exposure contributes to more than 5.5 million CVD deaths annually. Heavy metals—many released through mining, smelting, coal burning, and other industries, contaminating food, air, and water—are major contributors to cardiovascular disease. Even low levels of lead raise blood pressure and death risk, while cadmium is tied to artery disease, atherosclerosis, and heart failure through oxidative stress and blood vessel damage. Methylmercury increases the risk of artery narrowing and heart attack, copper promotes atherosclerosis through cell death, and arsenic is linked to early artery thickening and heart disease.

Evidence of harm grows, while heart health protections lag

The analysis builds on recent evidence associating cardiovascular health harms with environmental factors, even when exposure to toxins occurs below existing safety limits.

One 2024 study from Italy, for instance, linked long-term exposure to water contaminated with per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS, or “forever chemicals”) to a significant increase in cardiovascular-related deaths, while two others involving over 60 million Americans aged 65 and older revealed that even PM2.5 exposure levels deemed ‘safe’ significantly increased cardiovascular hospitalizations by about 29%. Long-term air pollution exposure may also severely worsen the risk of dangerous blood clots in deep veins, another study showed.

The new findings also come at a time when the EPA has proposed delaying and narrowing drinking water limits for key PFAS, despite new data that shows more than 172 million Americans are exposed to these chemicals in U.S. drinking water. The agency is also moving to repeal the legal basis for regulating greenhouse gases, and has extended industry compliance deadlines and granted exemptions to coal and industrial plants, prompting concerns about weaker oversight of toxic chemicals and air pollution.

Noise, extreme temperatures, and knowledge gaps

The research team also pointed to other types of environmental stressors that may impact cardiovascular health, though more information is needed. These include:

- Chronic noise from traffic, trains, and aircraft can stress hormones, disrupt sleep, and worsen risk factors such as high blood pressure, diabetes, and obesity, increasing the risks of high blood pressure, heart attack, and stroke. In Europe, tens of thousands of new cardiovascular cases each year are attributed to transport noise, with researchers warning the same is likely true in US cities.

- Climate change may compound health risks: Heat waves worsen smog, cold snaps strain the heart, and pollutants such as black carbon and methane both damage the cardiovascular system and fuel global warming, the review showed.

Despite extensive evidence, significant knowledge gaps remain, the researchers said. The long-term effects of lifelong noise exposure are not fully understood, nor are the risks of very low pollution levels.

Few studies examine how multiple pollutants interact, even though people are routinely exposed to them together. Threats such as wildfire smoke, desert dust storms, and artificial nighttime light also remain underexplored.

Population-based studies of micro- and nanoplastics and heart health are particularly needed, given their widespread presence, the scientists said. They also warned that most of the many thousands of manufacturer chemicals in use have never been tested and should be subjected to the same degree of regulatory scrutiny as pharmaceutical chemicals, they said.

Without even the most basic information on the potential toxicity of these widely used materials, it is impossible to estimate the magnitude of their harms to health,” the authors said.

Stronger policies could save millions of lives

City-level policies show promise, the researchers said. London’s Ultra Low Emission Zone is projected to prevent more than 1.4 million hospital admissions by 2050, while Bradford, England, has saved more than £30,000 (the equivalent of US$40,500) a month in national healthcare costs after introducing clean air zones. Similar measures are being considered in U.S. cities, but progress is slower.

At the global level, transitioning to 100% renewable energy system—dominated by solar and wind power—could cut major pollutants such as nitrogen oxides, sulfur dioxide, and fine particulate matter by up to 99% by 2050, delivering what the review called “double benefits” for both climate and heart health. Even smaller reductions than a complete phaseout of fossil fuel-related emissions would still deliver major cardiovascular health gains, the authors said.

Mitigation requires systemic interventions such as stricter pollution standards, noise regulations, sustainable urban design, and green infrastructure, they said. It should also include the adoption of innovative methods to measure tiny air pollutants and airborne chemicals on a large scale, particularly in cities where population exposure is highest.

“To reduce the cardiovascular burden of environmental risk factors, governments must adopt proactive and enforceable policies that prioritize public health, environmental sustainability, and equitable access to protective measures,” they concluded. “Integrating environmental determinants into CVD prevention strategies is essential to reducing morbidity and mortality on a global scale.”

Reference

Münzel T, Sørensen M, Lelieveld J, et al. A comprehensive review/expert statement on environmental risk factors of cardiovascular disease. Cardiovascular Research. Published online August 11, 2025. doi:10.1093/cvr/cvaf119