Two new studies underscore the urgency of research on microplastic, reporting that potential health and environmental risks from “leave-on” cosmetic and personal care products are largely ignored by researchers and regulators.

Moreover, immediate action is needed to better understand how microplastic overall degrades and take precautions, researchers say.

“Environmental contamination could double by 2040 and widescale harm has been predicted,” says renowned marine scientist Prof. Richard C. Thompson in a review paper published last month [September 2024] in the journal Science—two decades after he coined the term “microplastics.”

“Public concern is increasing and diverse measures to address microplastics pollution are being considered in international negotiations. Clear evidence on the efficacy of potential solutions is now needed to address the issue and to minimize the risks of unintended consequences.”

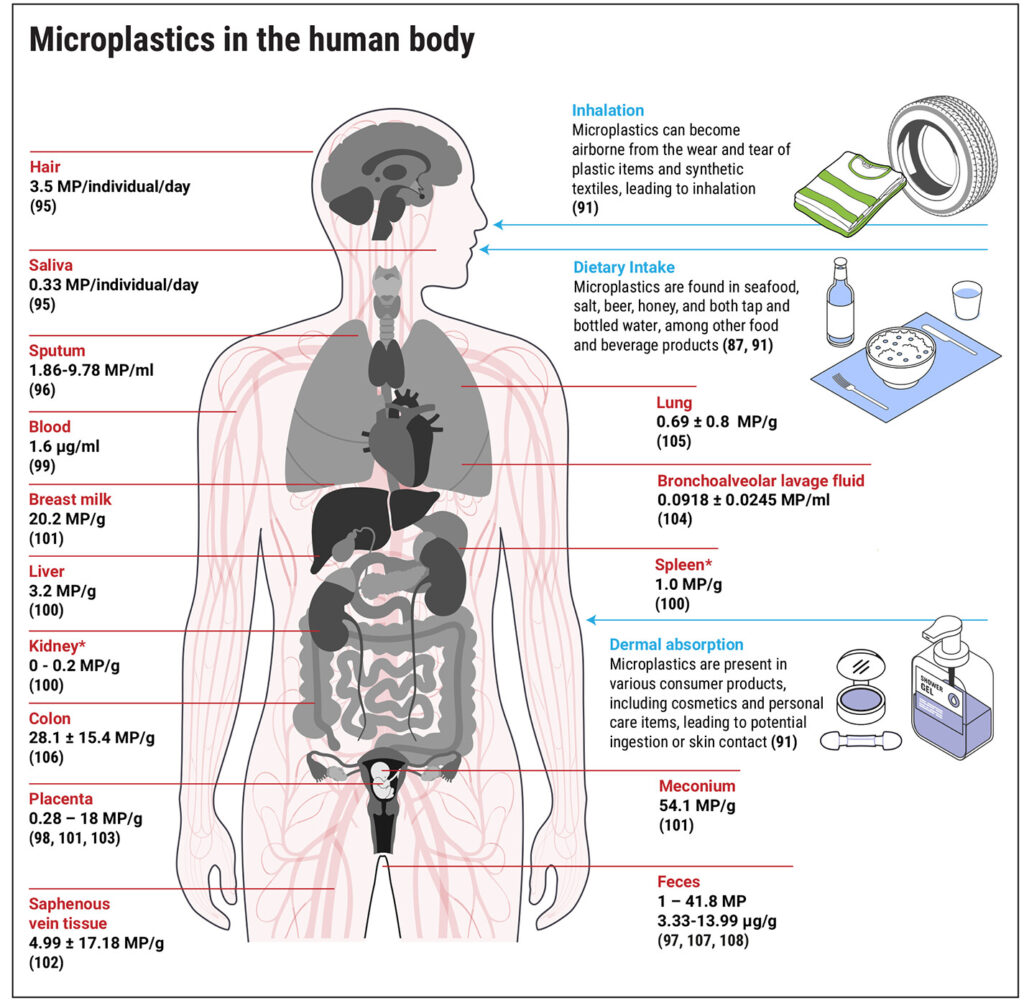

Microplastic describes the tiny bits of plastic particles (typically 5mm or smaller) that persist in the natural environment from sources such as tires, textiles, plastic-coated fertilizers, and paint. It’s found in food and drink and everywhere from deep sea sediments, reef-building corals, and the summit of Mount Everest to human breast milk, placental tissue, and blood.

Most recently, scientists found microplastic in the part of the human brain involved in the sense of smell (olfactory bulb), which suggests a potential route for plastic to enter the brain.

“Leave-on” cosmetics and personal care products include items like sunscreens, moisturizers, and deodorants. They contain microplastic that can be ingested, inhaled or absorbed through the skin. Packaging may also shed secondary microplastic debris into products, say University of Birmingham researchers in a study published last month [September 2024] in the Journal of Hazardous Materials.

A lack of testing on microplastic in “leave-on” cosmetics and personal care products means significant aspects of microplastic contamination are not investigated, even though they are purchased more than “rinse-off” products like soap or toothpaste—say the researchers, led by Dr. Anna Kukkola.

It also means that the impacts of microplastic emissions from these products are overlooked when it comes to regulations and legislation, they say. Of the nearly 2,400 products the team reviewed across 38 studies, only two were “leave-on” products. Various soaps, body scrubs, face scrubs, and toothpaste comprised the majority of all tested products.

“The contribution of ‘leave-on’ cosmetics to microplastic pollution is a critical, yet underexplored aspect of environmental contamination,” Kukkola says. “These particles will eventually end up in wastewater treatment plants or landfills, from which they can reach aquatic environments.

“What’s more, despite the likely extensive skin exposure to microplastics through such products, there is a surprising lack of research to investigate the associated health effects, with no studies found on microplastic exposure identified in this review.”

After examining more than 7,000 research studies on microplastic, Thompson and his colleagues agree that critical knowledge gaps remain. Thompson directs the Marine Institute at the University of Plymouth in England, and founded and heads its International Marine Litter Research Unit, which charted the global distribution of microplastic from Arctic sea ice to the deep seas.

For example, researchers have yet to determine the rate at which large plastic (macroplastic) breaks down into microplastic and the extent to which microplastic potentially fragments into even smaller particles (nanoplastic). The time required for plastic to convert into mineral substances is also unknown.

The research gap in microplastic in “leave-on” cosmetic and personal care items, in particular, could be due to the difficulty of testing these types of products. They contain more ingredients and complex formulations than their “rinse-off” counterparts, researchers say.

Scientists recommend:

- Research and regulatory testing should include both “rinse-off” and “leave-on” cosmetic and personal care products and more balance in the types of plastics and species studied. (For example, 62% of all toxicity assessments use polystyrene or polyethylene particles, says Thompson.)

- Results should report both the number and mass of detected microplastics to more accurately calculate environmental and human exposure burdens and inform any policy changes and assessments.

- Proposed and emerging alternatives to plastic should undergo early assessment, using safe and sustainable design principles, to address problems before they reach the market.

Comprehensive regulations and monitoring of all cosmetic microplastics are also needed, according to the new studies. Global regulatory frameworks currently focus on microplastic emissions of “rinse-off” products only.

In the U.S., for instance, the Microbead-Free Waters Act of 2015 prohibited the manufacturing, packaging, and distribution of “rinse-off” cosmetics that contain plastic microbeads. It does not address consumer safety.

The new European Union (EU) microplastic ban is the only measure that University of Birmingham researchers say “adequately” addresses leave-on cosmetics. However, the ban comes into effect in stages — 2027 for “rinse-off” cosmetics, 2029 for “leave-on” cosmetics, and 2035 for lip, nail, and makeup products.

That phase-out period makes it hard to keep up with the sheer volume of products containing microplastics that are produced and sold. Add to that the global scale of microplastic contamination, Thomas says, especially given the “near-impossibility of its removal once dispersed.”

References:

Kukkola, A., et al. Beyond microbeads: Examining the role of cosmetics in microplastic pollution and spotlighting unanswered questions. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2024; 476: 135053 DOI: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2024.135053

Thompson, Richard C., et al. “Twenty years of microplastics pollution research—what have we learned?” Science, 19 Sept. 2024, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adl2746

University of Birmingham news release. “Scientists warn of gaps in our understanding of leave-on personal care and cosmetic products. Sept. 30, 2024.

Related:

- Bikiaris N, Nikolaidis NF, Barmpalexis P. Microplastics (MPs) in Cosmetics: A Review on Their Presence in Personal-Care, Cosmetic, and Cleaning Products (PCCPs) and Sustainable Alternatives from Biobased and Biodegradable Polymers. Cosmetics. 2024; 11(5):145. https://doi.org/10.3390/cosmetics11050145

- Bourzac, Katherine. “First Comprehensive Plastics Database Tallies Staggering 16,000 Chemicals—And It’s Still Incomplete.” Scientific American. March 14, 2024.

- Christopher, E.A., Christopher-de Vries, Y., Devadoss, A. et al. “Impacts of micro- and nanoplastics on early-life health: a roadmap towards risk assessment.” Micropl.&Nanopl. 4, 13 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43591-024-00089-3

- Guerranti, C., et al. “Microplastics in cosmetics: Environmental issues and needs for global bans.” Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology, vol. 68, May 2019, pp. 75–79, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.etap.2019.03.007.

- Mohamed Nor NH, Kooi M, Diepens NJ, Koelmans AA. “Lifetime Accumulation of Microplastic in Children and Adults.” Environ Sci Technol. 2021 Apr 20;55(8):5084-5096. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.0c07384.

- Nature, Editorial. “Microplastics are everywhere — we need to understand how they affect human health.” Nat Med 30, 913 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-024-02968-x

- Patrick L, Pizzorno J. Impact of Microplastics and Nanoplastics on Human Health. Integr Med (Encinitas). 2024 Sep;23(4):6-9. PMID: 39355419; PMCID: PMC11441581.

- Prata, Joana Correia, et al. “Environmental exposure to microplastics: An overview on possible human health effects.” Science of The Total Environment, vol. 702, Feb. 2020, p. 134455, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134455

- Vethaak AD, Legler J. “Microplastics and human health.” Science. 2021 Feb 12;371(6530):672-674. doi: 10.1126/science.abe5041