Rusty-patched bumble bees: They’re on posters. They’re on stickers. They’ve even been turned into plush toys.

But one place you will no longer find these creatures: New York state. The yellow-and-black bees, now endangered, used to be common there.

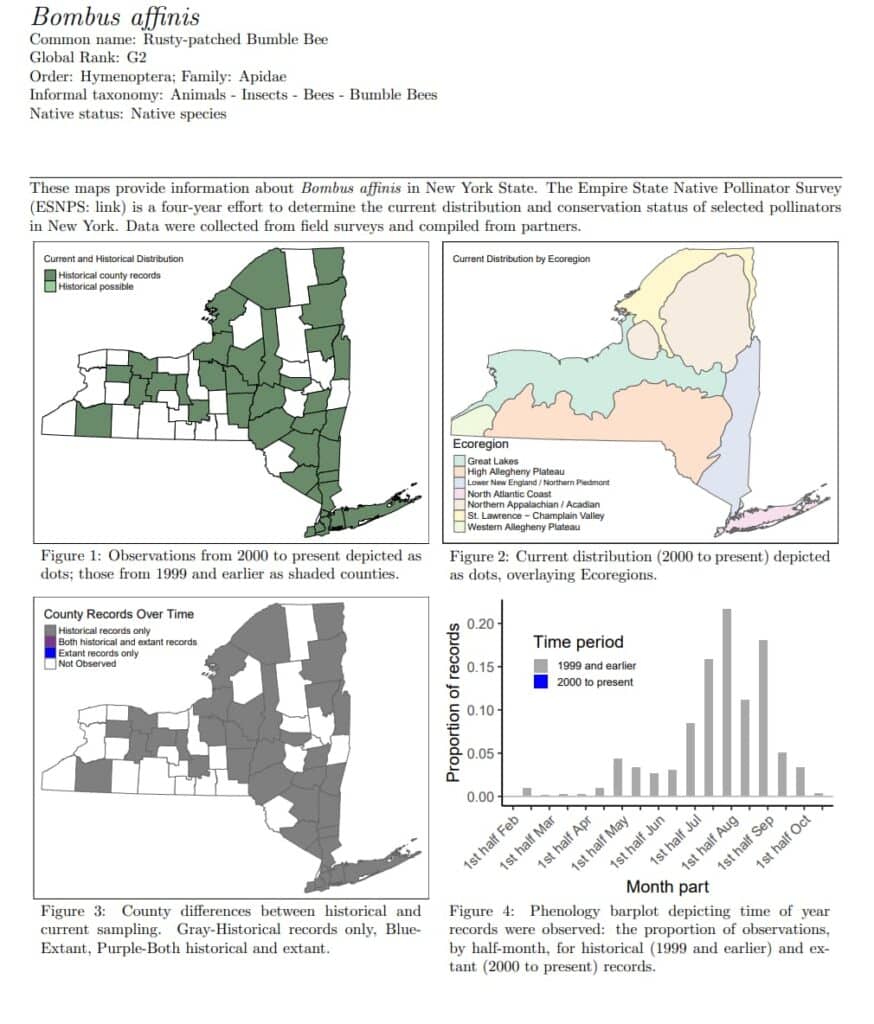

Scientists who conducted the Empire State Native Pollinator Survey found that not only had the rusty-patched bumble bees disappeared, but that as many as 60 percent of the state’s native pollinators were in danger of vanishing from New York completely. Using the most conservative criteria, 38 percent of the species that were studied were at risk of disappearing from the state.

“I think it is a really sobering finding, and it really matches some of the other literature and studies on insect declines,” said Matthew Schlesinger, chief zoologist for the New York Natural Heritage Program, which conducted the survey.

“All insects, to some degree, are threatened by pesticide use and habitat loss and climate change,” he said.

“That doesn’t mean they’re all going to disappear tomorrow. Some of them are just rare and have always been rare. But it’s true that rarity is one of the factors that can lead to extinction.”

Schlesinger and a team of academic scientists, citizen scientists and other experts from universities, museums and nonprofit groups collected data on more than 400 species of four types of pollinators – beetles, bees, flies and moths – from 2017 to 2020. They compared contemporary field observations with records of insect sightings from museum databases, insect collections and other records that went back to the 1800s.

“Every group had something like 20 species that hadn’t been seen in New York in 50 years or more, or since before 2000,” Schlesinger said.

Mapping a vanishing species:

Neonicotinoid restrictions in New York: The ‘Bird and Bees’ Act

The pollinator survey results were published in 2022. At the end of 2023, New York Gov. Kathy Hochul signed into law the “Birds and Bees” Act, which, in order to protect pollinators and other species, restricted the use of neonicotinoid pesticides on certain seeds, ornamental plants and turf.

To use neonicotinoids in New York, individuals not only have to complete a course in their handling and use. They also have to secure permission from two separate state offices for a determination that it is “an appropriate emergency” to justify their use.

With the passage of the law, New York was the first state in the nation to restrict neonicotinoid seed treatments, the most widely used insecticides in history. Ten other states have restricted the use of neonicotinoids: California, Colorado, Maine, Maryland, Minnesota, Nevada, New Jersey, Rhode Island, Washington state and Vermont. In recent years, the insecticides have also been banned for outdoor use in Québec and the European Union.

New York Assembly Member Deborah J. Glick, who sponsored the “Birds and Bees” Act, said that the news about the dangers facing pollinators in the state, along with extensive scientific literature linking those losses to the use of neonicotinoid insecticides, informed the legislation.

“In my humble opinion, there was overwhelming evidence that it was an effect not just on honeybees but on all native species,” said Glick, a Democrat who represents parts of lower Manhattan. She credited a compilation of studies as factors in the legislation.

“I am very grateful to all of the scientists who do the laborious work that provides data.”

One of those studies, released in 2020 by researchers at Cornell University, found that neonicotinoid-treated seeds increased risks to pollinators while not increasing net income for the state’s corn and soybean producers.

Two hundred citizen scientists

For the state Natural Heritage Project’s large-scale study on pollinators, more than 200 citizen scientists participated in field studies. In all, more than 34,000 individual specimens were identified to the species level during three years of surveying every county in New York.

The locations of specimens that field workers collected and photographed were compared to detailed records from museums, scientific journals, nonprofit listings and even Facebook pages.

Sarina Jepsen, director of endangered species for the nonprofit Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation, lauded the Natural Heritage Program’s approach.

The extensive use of museum records “underscores the important role that museum collections can play in understanding the changes that may have occurred in the pollinator community of a particular area,” she wrote in an email. “The Empire State Pollinator Survey is a great model that hopefully will be replicated in other regions.”

The goal, Schlesinger said, was to assess whether a species that had been spotted in a county in the past – even the distant past – was still present during the survey.

“We use a method that tells the relative change compared to other species,” he said.

They didn’t count insects. Rather, they examined their spatial spread. How many of these species appeared in each county?

“Are we not able to find it in places where it used to be found?” Schlesinger said. “And vice versa. So that’s what the trend is based on.”

The academic team created digital maps with layers that showed several variables: Whether a species had been recorded in an area before 1999, whether it had been recorded after 2000, and whether it had been identified during the recent survey period. The maps also included data by ecoregions, such as the Great Lakes and the North Atlantic Coast, as well as county-level distributions.

The distribution data, combined with reviews of scientific literature and expert assessments of threats to the insects, contributed to the determination of the conservation status of each species. Each received a rank on a 6-point scale that ranged from “apparently secure” to “presumed extirpated,” which meant that the insects had not been located despite intensive searches with “virtually no likelihood that it will be rediscovered.”

In a few cases, they found good news. Eight species of bees that had been targeted for conservation were added to the list of known species in the state. The Bombus terricola, or yellow-banded bumblebee, is a candidate for the federal endangered list. These bumble bees were more common in New York than the team expected them to be.

“They’re doing OK, in New York,” Schlesinger said, “and that was comforting.”

The team found other bees, such as the golden northern bumble bee, in places where they did not expect to find them.

“New York City, of all things, was a hot spot,” Schlesinger said.

He credits the increases in some species to public awareness and a desire to make the world better for pollinators.

“The movement to not have a sterile green lawn has really picked up steam,” he said, “and a lot of people have much more pollinator-friendly lawns and are reducing their pesticide use. So it’s more habitat and fewer toxins, and I think those are really critical things for improving pollinator health.”

The data from the Natural Heritage Program have been used by conservationists and landscape architects alike. A company in the Hudson Valley drew on the research to develop a program called “Pollinate Now!” for homeowners who want to create better habitats for those insects.

In the next year, Schlesinger said, the findings could factor into New York’s state wildlife action plan. States are currently developing these plans, which are used to apply for federal grant funding. For New York, a “couple of hundred” pollinator species could be listed as “species of greatest conservation need,” Schlesinger said.

Some species could get onto the state’s endangered species list as well.

“Sometimes we write reports that sit on shelves,” Schlesinger said. “but this one is getting a little more traction, because there’s been so much interest in pollinators.

“That is very satisfying when you get to see that. . . . We generate and provide data. That’s our job. When we get to see it put to use, for conservation benefits, it’s really rewarding.”