Back in 2014, the headlines lit up with bad news about declines in bee health, and scientific research tied that decline to the rise in the use of neonicotinoid pesticides.

In the midst of this onslaught of news, Bayer Crop Science opened the “Bayer Bee Care Center” in North Carolina, to great fanfare. It was the site of a flurry of bee research and public tour groups for five years. Within a year, it drew television news coverage.

Then, in 2015, one other significant development cropped up: Bayer, along with the public relations firm Porter Novelli, was named a finalist for two national PR awards for the bee care team as an exemplary form of crisis public relations. For PR Week, the effort was a candidate in the “Crisis of Issues Management Campaign of the Year.” For PR News, the 2014 Bayer North America Bee Care Program was up for a platinum award in crisis management.

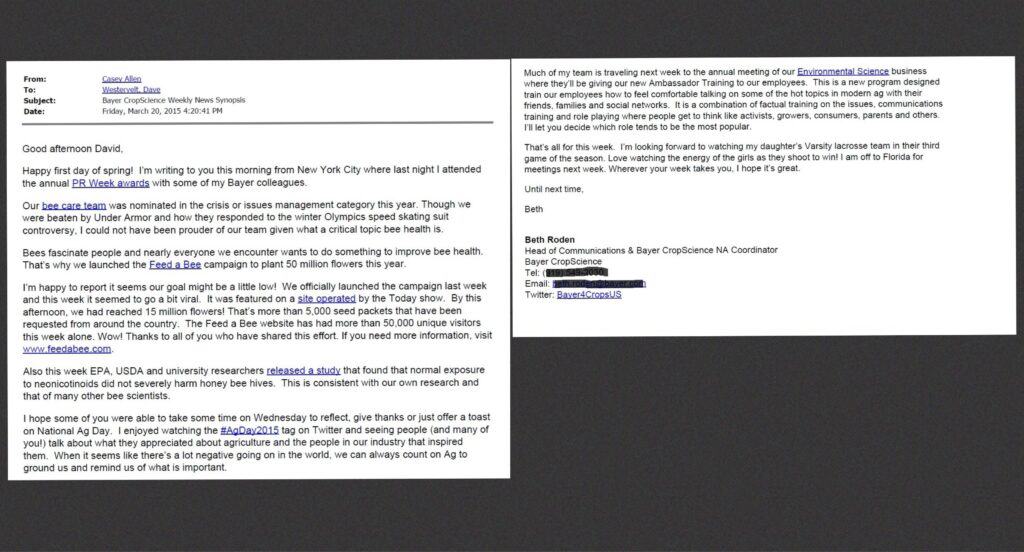

Further, a Bayer executive touted the recognition for the team as crisis PR in a company newsletter, which was acquired by U.S. Right to Know through the Florida Sunshine Act.

In the newsletter, dated March 20, 2015, Beth Roden, now senior vice president and head of communications for Bayer U.S., wrote that “our bee care team was nominated in the crisis or issues management category this year. Though we were beaten by Under Armor and how they responded to the winter Olympics speed skating suit controversy, I could not have been prouder of our team given what a critical topic bee health is.”

Other finalists in the crisis PR category for PR Week that year were the U.S. Farmers and Ranchers Alliance with a documentary to improve public perceptions of U.S. agriculture, the Carnival Corp. with a campaign to orchestrate the comeback of the cruise company, and a campaign by Tenet Health after a whistleblower lawsuit alleged in 2014 that the healthcare system paid kickbacks to doctors in Florida for referrals of pregnant, undocumented Hispanic women.

Paul Argenti, a professor of corporate communications at Tuck Business School at Dartmouth University, described the Bayer bee care project as “very sophisticated, mind-altering public relations activity at its best.

“This is so blatant,” Argenti said.

“I don’t think I’ve seen anything this bad before. The issue is: How do they justify their behavior? If this is actually a product that kills bees, how can you then open up a center and try to show how much you love bees?”

“This is so blatant. I don’t think I’ve seen anything this bad before.”

– Paul Argenti, professor of corporate communications, Dartmouth University

In the newsletter that touted the public relations award, Roden also pushed news about national coverage of the company’s “Feed a Bee” program, which was part of the bee care project and had its own hashtag on Twitter. She also noted a study by the U.S. Department of Agriculture that found that “normal exposure to neonicotinoids did not severely harm honey bee hives. This is consistent with our own research and that of many other bee scientists.”

Public statements by the company posit that bee health has declined because of genetics, disease, climate change and Varroa mite infestation of hives. Decades of academic research point to neonicotinoids – the most widely used pesticides in human history – as a factor in declining bee populations as well.

The Bayer Bee Care Center, a 6,000-square-foot, LEED-certified building that cost $2.4 million, opened in Research Triangle Park, N.C., in April 2014. On opening day, corporate officials displayed artwork by schoolchildren, a full library with an apiary, training facilities for beekeepers and office space for staff scientists and graduate researchers, according to a press release.

Scientists attended seminars there. Three thousand visitors toured during the first year, with 10,000 visiting by 2017. Pat McCrory, governor of North Carolina at the time, issued an official proclamation of a state “Honey Bee Day,” which was announced at the center on its first anniversary. In a press release, Gov. McCrory congratulated Bayer Crop Science for “the remarkable achievements made in just one short year.”

Further, Bayer assembled a research panel that, according to documents acquired by U.S. Right to Know, avoided addressing the effects of neonicotinoids on bees. According to press releases, the company spent $12 million on bee health that year.

At least one university scientist attended the grand opening, along with graduate students from Virginia Tech. According to documents acquired through the Virginia Freedom of Information Act by U.S. Right to Know, Bayer executives pressed the professor, Troy Anderson, who now works at the University of Nebraska, to get his students to attend the grand opening.

Anderson did not respond to a request for comment.

Argenti said that company officials’ focus on bringing in graduate students showed an interest in influencing future research in the area.

“If you really want to have an impact, then you want to change the course of science going forward,” he said.

“ . . . They were determined to change the course of research in this area, and to influence the way that research would come out.”

Influencing research is nothing new to Bayer; in 2014 and 2015, company officials pressured academic scientists in 2014 and 2015 to exclude from publication photos of insecticide-coated corn seeds that appeared to be defective, according to a story published in 2022 by U.S. Right to Know.

According to a company press release, the Bee Care Center’s mission was to serve “as a hub for premier technological, scientific and academic resources to protect and improve honey bee health and sustainable agriculture.”

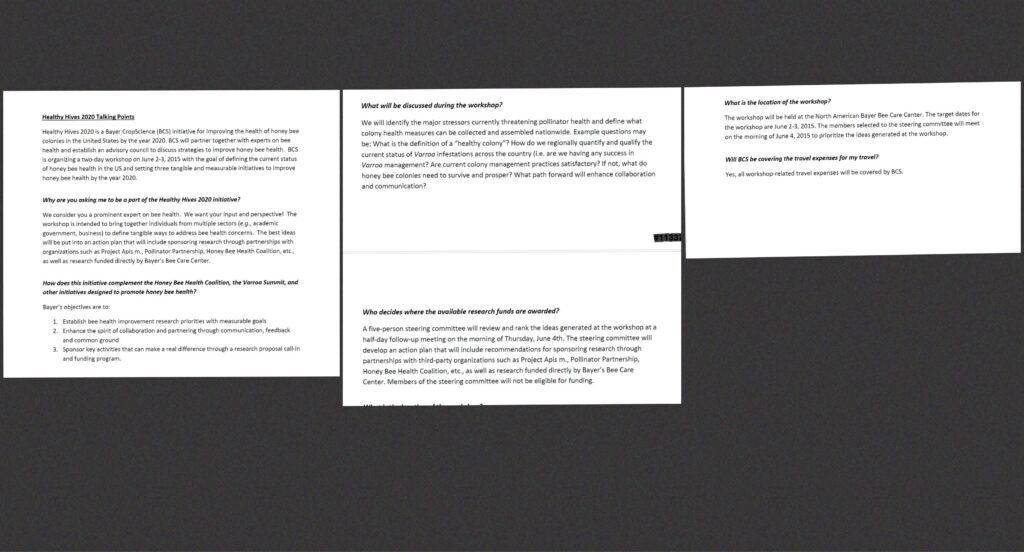

The month after the Bee Care Center opened, the company convened a panel of scientists for a group called Healthy Hives 2020, which met at the center. Some of the most well-known and regularly published bee scientists in the country participated, according to documents acquired by U.S. Right to Know.

In one document, company officials suggested example questions to the steering committee about definition of a healthy colony, quantifying Varroa mite infestations and examining beekeepers’ colony management.

Prominent scientists who were invited to the first Healthy Hives meeting in 2015 included Jay Evans, a research entomologist at the U.S. Department of Agriculture Bee Research Laboratory in Beltsville, Md.; Reed Johnson, a professor of entomology at Ohio State University who gave the keynote address at the American Bee Research conference last year; and David Westervelt, the retired chief of apiary for the state of Florida.

Now, the designated account for Bayer Bee Care on the social media platform X, formerly known as Twitter, is dead. The Web link to the Healthy Hives initiative is dead as well.

Further, the bad news about the bees has largely faded from the headlines.

Robin Cohn, a crisis PR specialist and author of “The Crisis PR Bible” said that she was surprised that in the extensive press coverage of events at the Bee Care Center, reporters did not ask about the role of Bayer’s products in the decline of bees.

“When I deal with crisis, I wish I had that,” she said.

The bee care campaign, she said, “took away the attention to their product. In that respect, it was a successful campaign.”

But while the company’s reputation improved, she said, the ethics were questionable, because the goal of crisis PR is to fix the underlying problem.

“It really looks good. They put money into it, and science, and children. The underlying problem wasn’t fixed. But their reputation was fixed.”

According to documents acquired by U.S. Right to Know, officials for the Agricultural Research Service in North Carolina prepared a proposal to take over the Bee Care Center. Officials in North Carolina did not respond to questions about the outcome of that proposal.

The closure of the Bayer Bee Care Center was announced in a LinkedIn post by its director, Dick Rogers, in 2019. If the company issued a press release about the closure, no links to it survive.

Rogers wrote:

“It is sad to say goodbye. . . . We will continue to work on improving bee health and shaping apiculture through research and technology, but from a new location starting late 2019.”

A spokesman for Bayer, the company that spent $12 million on a bee care team 10 years ago, did not respond to questions about the team’s ultimate fate.