In 2018, Louis Robert, an agronomist in Québec, was fired after releasing controversial research about the limited effectiveness of neonicotinoid pesticides.

After a year of asking his superiors at the Ministry of Agriculture to release the report, Robert sent the unpublished research to Radio-Canada.

The upshot of the study: That neonicotinoid seed treatments produced no significant difference in crop yields for corn and soybeans.

Shortly after he released the report to the press, while he was in a field giving a demonstration to farmers, Robert’s phone rang. It was his boss’s secretary, insisting that he return to the office immediately.

“As soon as I got to the office, I was invited to a conference room, and my boss was there, and on the video was his boss in Québec City, and they handed me a letter signed by my ministry,” Robert said. “I was suspended from the department.”

The research that his superiors kept under wraps was one of several studies in the last decade that have shown that in corn and soybeans, the economic benefits of using pesticide-treated seeds are questionable.

“Their research was clearly showing that those products were not giving any benefits to farmers,” Robert said. “But, at the same time, they were told by their bosses, by the board of directors, to not present those results to the outside world, and keep them to themselves for the time being.”

In Québec, in New York State and in Vermont, the findings of this study and others with similar conclusions contributed to the passage of laws that restricted the use of the insecticides, according to lawmakers and scientists.

This year, four more states are moving to limit the use of neonics, in addition to the 10 states that have already restricted. Discussion of economic benefits of the pesticides to farmers and consumers typically factor into these decisions.

Public drama in Québec

After Robert’s firing in Québec, public drama ensued. In fact, Robert wrote a book about it, called “Pour le bien de la terre,” or “For the good of the earth,” published by Éditions MultiMondes.

After the government received a petition with 17,000 signatures, and members of the public marched on the parliament in Québec City (during “the coldest day of winter,” Robert said), he was reinstated. Québec Premier François Legault and André Lamontagne, the minister of agriculture, issued personal apologies for the firing.

Robert said that people in Québec are aware of the issue, because of his story.

“It was a huge scandal in Québec,” he said. “Nowadays, most people in Québec are aware of what is a neonic and what damage it does to bees and pollinators.”

Beyond Québec, a growing body of research is showing that fields often do not contain enough “insect pressure” – or, presence and number of insects in a field or a crop – to justify the rate at which neonicotinoid-treated seeds are used. In fact, data from the Canadian province Ontario have shown that crop yields for corn and soybeans increased after farmers stopped using them.

The most-used pesticides in history

Thirty years after neonicotinoids were first introduced, they became the most widely used class of pesticides in the world, and the most-used pesticides in human history.

“Neonics are a vital resource for farmers.” -Kyel Richard, spokesman, Bayer Crop Science

According to an extensive body of research, the insecticides, which were introduced by Bayer in the 1990s, conferred several benefits over previous chemicals: They controlled many different kinds of pests, they protected all parts of the plant, they didn’t require labor-intensive application methods, and they were less toxic to people who apply pesticides than the chemicals that were used previously, such as pyrethroids, carbamates and organophosphates.

The downside of using treated seeds: Neonicotinoids threaten the health of bees and other pollinators, according to hundreds of peer-reviewed studies.

Also, according to a review of scientific literature published this year, contamination of bodies of freshwater near croplands has produced toxic effects on mollusks, insects, frogs and fish. Another review, published in 2024, showed “consistent negative effects of neonicotinoid exposure on various levels of performance of birds,” and that direct effects are responsible for part of the global declines in bird populations.

Manufacturers of neonicotinoids posit that the insecticides are safe for the environment when used correctly.

“Neonics are a vital resource for farmers,” Kyel Richard, a spokesman for Bayer, wrote in an email. “Farmers rely on neonicotinoids to optimize crop yield and quality and they would be forced to use more or less effective and/or harsher alternatives if neonics were no longer available.”

Even so, findings on crop yields have led researchers to question the need for these insecticides.

“If you don’t have any pests, you don’t have any pest management benefits.” -Christian Krupke, professor of entomology, Purdue University

“If you don’t have any pests, you don’t have any pest management benefits, right?” said Christian Krupke, professor of entomology at Purdue University.

“What these data show, on some of these large-acreage crops, is that where we’re using these insecticides the most, seems to be where we need them the least. So there’s a real disconnect between pest pressure, economic damage level and use rate.

“That’s where we get into the problem of, ‘OK, why are we doing this, again?’ “

Industry-funded research shows improved crop yields

Representatives of Bayer and BASF responded to detailed written questions about the science by pointing to industry-funded research that showed substantial increases in crop yields.

Representatives for Corteva Agriscience and CropLife America, a trade association for the pesticide industry, did not respond to repeated email questions about contradictory research findings. Representatives for Syngenta, another manufacturer of neonicotinoids, declined to comment.

None of the representatives of the manufacturers, or CropLife America, responded to questions about academic research that contradicts industry findings or the pushback that Robert and other scientists have reported.

Richard, the Bayer spokesman, referred to publicly available research, released in 2014, that was funded by Bayer Crop Science, Syngenta and Valent U.S.A.

The report, a meta-analysis of 1,500 studies that included both peer-reviewed research and results of field experiments from private company databases, showed that “the average yield benefit [an increase in crop yields] ranges from 3.6 percent for soybeans to 71.3 percent for potato.” The analysis also showed yield benefits for corn, wheat and cotton of about 17 percent, and 20 percent for sorghum.

Industry research: Without neonics, farmers would need to add five pounds of older chemicals for every one pound of neonicotinoids lost.

“Based on these results,” the study concluded, “neonicotinoid insecticides generate substantial yield benefits.”

Chip Shilling, a spokesman for BASF, noted by email that corn and soybean seeds treated with its clothianidin products produced substantially higher bushels per acre than non-treated seeds. In 526 tests conducted by universities, seed companies and consultants, he wrote, corn seed protected with Poncho® 250 seed treatment yielded an average of 9.74 bushels per acre more than non-treated seed.

In more than 936 head-to-head comparisons, Shilling wrote, corn seed treated with Poncho® 1250, a higher treatment rate, yielded an average of 13.5 bushels per acre more than non-treated seed.

According to a fact sheet produced by pesticide manufacturers, without neonics, farmers would need to add five pounds of older chemicals for every one pound of neonicotinoids lost. However, this need may be diminishing as anthranilic diamides, a newer class of pesticides, reaches wider use, according to research literature.

An executive summary of the findings, produced by the public relations firm Porter Novelli, stated that farmers would incur increased costs without the use of neonicotinoid pesticides because alternatives are more expensive, and they would have to seed and spray more frequently to get the same yields.

Paul Mitchell, director of the Renk Agribusiness Institute at the University of Wisconsin at Madison, was the author of the report. In an email, he questioned the approach of the entomologists.

“If so many [of] the farmers are doing this and getting no value, it really begs the social question: Why? Are almost all farmers that dumb to keep losing money over that many acres year after year or do the entomologists not quite understand something about the value farmers get from the seed treatments?

“As a social scientist, I think the entomologists are asking the wrong question: what is the source of value that they are getting? Many of them have a hard time accepting insurance use of insecticides, but then wear their seat belts every day when they drive. I have spent the time, effort and money to have seat belts in my car and wear it religiously, but I have never gotten one cent in direct benefit from it (so far no accidents), but I still get value from wearing it. The big difference is that wearing seat belts does not generate negative externalities like insecticides do in the environment.”

Krupke said that the public needs more data to establish the risks and benefits of using neonicotinoid-treated seeds.

“Peer-reviewed field studies (by industry and public sector scientists alike) demonstrating consistent benefits of the seed treatment approach to insect pest management in row crops are remarkably scarce,” he wrote in an email.

“This is surprising when you consider we plant these crops over many millions of acres each year in the U.S.”

He advocated for further research in fields with and without treated seeds. Those data should be more plentiful as more jurisdictions limit the use of neonicotinoids.

“We have ample opportunity to study the costs and benefits,” Krupke wrote.

As scientists report intimidation, four states introduce bills to limit neonics

In addition to New York and Vermont, eight other states have limited the use of neonicotinoids.

As legislators in four more states consider bills this year to limit neonicotinoids, crop yield research will likely continue to factor prominently in public debate. Lawmakers in Connecticut, Arizona, Massachusetts and Hawaii have introduced bills to limit use of the pesticides, according to Kate Burgess, the conservation manager for the National Caucus of Environmental Legislators.

“This is the most controversial topic in entomology.” -Scott McArt, associate professor of entomology, Cornell University

Further, Missouri legislators have introduced a bill to restrict equipment to apply neonicotinoids, and a bill in Indiana would initiate research on the impact of the use of the pesticides in the state, according to Burgess. The report in Indiana would provide recommendations to legislators based on findings.

The role of crop yield research in setting policy on the use of the pesticides at the state and province level has drawn intense scrutiny to findings.

Limiting the use of treated seeds has fallen to the states. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has determined that the seeds do not qualify as standalone pesticides, and that the federal rules that govern the use, labeling and safety reviews of pesticides do not apply to them. A recent federal court decision upheld that determination.

In addition to Robert, at least one other scientist has faced career trouble after publishing research that shows minimal economic benefits of using neonicotinoid-treated seeds.

“The pesticide industry tried to get me fired,” said Scott McArt, an associate professor of entomology at Cornell University who studied the topic.

When he was commissioned to do the research by the administration of former Gov. Andrew Cuomo, he said, “I knew that if we were going to do something substantial on this, it’s playing with fire.

“I did meet with the associate dean to say, listen, if we take this on, I’m not going to just do it as a three-page document. We’re going to do a real risk assessment here. . . . Just so you know, this is the most controversial topic in entomology.”

McArt was correct about the potential for controversy. After the research was published, industry scientists questioned his methods by sending email that was copied to his dean, he said.

“I never guessed that you would have pesticide industry folks emailing me, saying ‘We’re a little bit uncomfortable with how this analysis was done.’”

“I had to meet with university lawyers to figure out how to respond,” he said.

None of the industry representatives responded to questions about research-related inquiries to McArt or other scientists.

McArt’s research was questioned by an industry scientist in public as well.

In 2021, the first time a bill to ban neonicotinoids came up before the New York State Assembly, Sean McGee, a senior ecotoxicologist and risk assessor for Bayer, said that McArt’s research did not include all the studies that were reviewed by the Environmental Protection Agency when the agency approved the registration of neonicotinoids.

“It was incomplete,” McGee said of McArt’s research during his testimony.

“In the absence of a defined approach, they just said, ‘there’s the presence of a neonicotinoid, there must be an effect.’ That’s not risk assessment. That’s presence equals hazard.

“If that were the case, none of us would be drinking caffeine. Caffeine is ten times more toxic to humans than neonics are, but we drink it every day, knowing that the exposure I’m going to get is not one at toxic levels.”

After that testimony, McArt said, “I had to get up after he gave this testimony and try to explain why what he said was inaccurate.”

He said it was a “huge challenge” to explain risk assessment protocols to non-scientists.

The bill was tabled in New York that year, not to return until the next session, after which it passed.

Research: Neonics rarely produce economic benefits for corn and soybean crops

McArt’s research, conducted over four years, showed that while the insecticides – including imidacloprid, clothianidin and thiamethoxam – are highly beneficial in fruits, vegetables, ornamental uses, conservation and forestry, they rarely benefit crop yields in corn and soybeans.

For corn, he found that 94 percent of the time, the use of the treated seeds produced no economic benefit for farmers. For soybeans, that number was 93 percent.

“The pests are just not very frequent,” McArt said.

“The pests are just not very frequent.” -Scott McArt, associate professor of entomology, Cornell University

In short, he and other researchers conclude, the treated seeds serve more as an “insurance policy” against a rare catastrophic crop loss than as a routine check against pests.

To determine risks and benefits of using neonicotinoids, McArt’s team synthesized all research on risk to pollinators – more than 400 peer-reviewed studies – and research on economic benefits to farmers, which incorporated more than 5,000 paired neonicotinoid and controlled field trials.

The synthesis of the studies on pollinator risks showed high risks in and around corn and soybean fields, with 74 percent of exposures likely to affect honey bee physiology, 58 percent likely to affect honey bee behavior and 37 percent likely to affect honey bee reproduction.

In the synthesis of thousands of studies on the effects of neonicotinoids on crop yields, McArt reported that 83 percent to 97 percent of field trials showed no significant increase or decrease in corn yield. Similarly, in soybean yield, 82 percent to 95 percent of field trials showed no significant increase or decrease.

These results differ from the industry-funded research, McArt wrote in an email, because “we used a much larger pool of literature for our review.

“We tapped into the extensive university extension literature, adding hundreds of data points that were not captured in the industry-funded review. We also benefited from several additional years of peer-reviewed publications (our review covered everything up until 2020).”

Cornell University: More than 90 percent of the time, neonic-treated seeds produced no economic benefit for corn and soybean crops.

Also, he wrote, his team did not use industry-funded studies that were not peer reviewed “because those studies typically left out important methodological details such as whether or not the fields were prepared in ways that augmented pest populations.”

Mitchell, the author of the industry-funded meta-analysis, wrote in an email that “it is common practice for corn rootworm studies to plant trap crops the year before to ensure egg laying and high larval pressure the subsequent year when the trial is conducted. This is a standard practice, that way you evaluate the treatment under high pressure for a key target pest.”

By contrast, McArt’s research, and the research of other academic researchers, has more closely resembled typical field growing conditions without increasing pest pressure.

In Indiana: 94 percent of honey bee foragers at risk of exposure to neonics with no economic benefit

In Indiana, Krupke of Purdue University performed a “concurrent multi-year field assessment of the pest management benefits of neonicotinoid-treated maize,” according to a summary of a study published in the Journal of Applied Ecology in 2017.

His team’s work showed that “94% of honey bee foragers throughout the state of Indiana are at risk of exposure to varying levels of neonicotinoid insecticides, including lethal levels, during sowing of maize. We documented no benefit of the insecticidal seed treatments for crop yield during the study.”

To make these assessments, the team conducted experiments in 12 fields by measuring the concentration of neonicotinoid residues during planting. They placed dust collection stations around the fields and quantified the amount of neonicotinoids that bees would encounter while foraging in the fields.

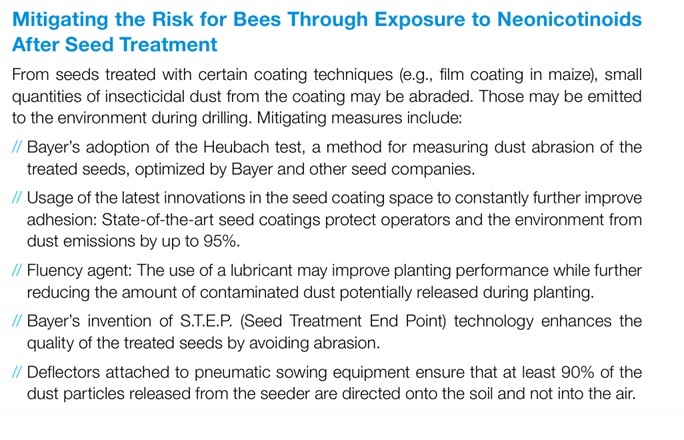

Krupke noted that since this research was conducted a decade ago, Bayer has developed polymers for seed treatments that result in less dust and less exposure to bees.

In its annual report on neonicotinoids, Bayer presented several steps the company has taken to mitigate exposures to bees from treated seeds:

After his research was published in 2017, Krupke fielded questions from industry scientists on his methods, execution and conclusions.

He wrote in an email that “I always welcome other data/perspectives, knowing that ours is not perfect or representative of every situation. I did not take it as undermining the work. I always hope these conversations will lead to follow up studies.”

Krupke’s study in Indiana also concluded that “three years of field experiments spread throughout the most intensive maize production region of Indiana failed to demonstrate a significant benefit of planting treated maize seeds,” which, the team pointed out, is consistent with findings from research on oilseed rape in the European Union and studies of soybeans in the United States.

In further conclusion, the report said: “These reports and our data suggest that the current use levels of insecticidal seed treatments in North American row crops are likely to far exceed the demonstrable need and our results likely reflect a scarcity of target pests.”

According to research published in Environmental Science and Technology in 2015, between 79 and 100 percent of maize hectares in the United States have been planted with neonicotinoid-treated seeds. Like others, that study concluded that “carefully targeted efforts could considerably reduce neonicotinoid use in field crops without yield declines or economic harm to farmers, reducing the potential for pest resistance, nontarget pest outbreaks, environmental contamination, and harm to wildlife, including pollinator species.”

Newer research about the extent of use of neonicotinoid-treated seeds is not available because the U.S. Geological Survey stopped collecting that data in 2015.

Hardier plants today “are far better equipped to navigate the challenges posed by insects” than 10 to 20 years ago. -Christian Krupke, professor of entomology, Purdue University

Krupke said that typically, when farmers buy seeds, they are not thinking about pre-treatment, and that every seed is treated with multiple compounds.

“When most farmers think about their overall costs – that topic, the pesticide on the seeds, it’s of relatively low importance,” he said.

“You cannot go and say, ‘I want [pesticides] 1 and 3 and 6, but I don’t want 2 and 4 and 5. It’s not like that.”

One other reason farmers could ditch the treated seeds is that modern plants are superior in many ways.

“One of the things that’s neglected when we talk about pest management and these crops,” Krupke said, “is that we’ve done so much excellent work breeding – just classical plant breeding – that these plants grow faster, they put on more biomass, they’re more competitive, they’re more cold-tolerant, they’re more drought-tolerant – they’re just much harder to stop.

“These plants, they are far better equipped to navigate the challenges posed by insects as well. Their genetics are far superior than those of crop plants from even 10-20 years ago.”

The problem for the growers, he said, is that they have a hard time getting the elite genetics – the topnotch varieties – without insecticides.

Krupke said that virtually all corn is treated with insecticides and fungicides, but that soybean seeds are more likely to be available without the treatments.

Technology and crop insurance: Solutions to neonic risks?

At Cornell University, where McArt has described treated seeds as an insurance policy, one of the recommendations in his report was to offer exactly that – better insurance policies, along with better models and methods to monitor for higher levels of pests that threaten crops.

In Cornell’s report for New York state, the team posited that “farmers expecting normal pest pressures might forgo seed treatments in exchange for more generous insurance covering potential damage from early-season pests. Inexpensive insurance would also allow farmers not using treated seeds to continue using cover crops and reduced tillage with confidence.”

But even then, farmers who reduce use of treated seeds in New York, which is phasing out neonicotinoid seed treatments in the next few years, may not need additional insurance policies.

McArt noted that corn and soybean yields have not changed since the European Union banned neonicotinoid seed treatments in 2018, and yields have increased in the Canadian province of Ontario since its ban on neonicotinoid seed treatments in 2017.

“There’s no reason to expect a different result in the USA,” McArt said.

“If we got rid of neonics,” McArt said, “is it going to devastate agriculture in the U.S.? No. We already have proof that that’s not true.”